Keeping the Pipe Just Full

In this post, I will be discussing a paper published by the Internet pioneer Leonard Kleinrock, titled “Keep the Pipe Just Full, But No Fuller”. The paper’s conclusion is that it is best to keep the internet “pipe” full, without overloading it. This idea is a take on Einstein’s famous quote, “Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Introduction

It’s not always true that using the network to its fullest capacity will lead to better performance. When the network is overloaded, congestion and queueing delays can occur, which can affect the rate at which useful data is delivered and the time it takes for data to be delivered. This means there is a tradeoff between goodput and latency. To avoid network issues, congestion management is important. TCP regulates data flow from source to destination by sending packets while monitoring the delivery rate and response time to manage congestion. The challenge is to regulate traffic flow, as both underutilizing and overloading the capacity can waste resources and cause congestion.

For many years, TCP congestion control algorithms have relied on loss as a measure of congestion. However, loss causes sawtooth behaviors as flow expands until packets are dropped, then shrinks. This inefficient hunting wastes resources and injects delay. Ideally, TCP should run at the onset of queuing, filling the “pipe” with minimal buffering rather than flooding it. This balances delay and delivery rate optimally. TCP BBR uses this approach by directly tracking bottleneck bandwidth and baseline round trip time.

The ideas presented in this paper were initially discussed back in 1978 but did not gain much attention because the thinking was that it would not work in a decentralized system. However, the Google BBR has shown that it can work in a distributed system if we estimate over a distributed amount of time using a sliding window approach.

Optimal efficiency is achieved when the average number of packets within network nodes is kept low. Counterintuitively, smaller queues perform better despite lower utilization. The paper shows that deterministic analysis suggests that one packet per node minimizes delay while still using nearly full bandwidth. Stochastic models confirm that an average of one packet provides the best balance.

The strategy of keeping the pipe just full maximizes power, which is the throughput divided by latency. Congestion control is shifting from blind overdrive to smart optimization based on real-time network state.

Recommended Background Reading

-

For a refresher on queueing theory and its applications, you can visit this old writeup which covers lot of fundamentals: Average Network Delay and Queuing Theory basics.

-

Additionally, look at various TCP congestion control behaviors:Experimenting with TCP Congestion control

Deterministic Intuition

When exploring a new area, we tend to create simple models to understand complex systems. For example, we might imagine a data network as a group of customers and a system that serves them. This helps us get a basic idea before diving into the messier details.

In our case, we measure network flow using a metric for Goodness, such as throughput, versus a Badness function, such as slow response. The goal is to maximize Goodness while minimizing Badness. To achieve this, we use deterministic reasoning, which assumes there’s no randomness in the arrival or service patterns.

Imagine a store with one cashier. The optimal state is when there’s always a customer at the checkout, meaning 100% utilization. If the store has two cashiers, the optimal state is when both cashiers are busy all the time. However, if we push the utilization too high, queues will form, and customers will get grumpy. The longer the queue, the longer the delay in servicing customers, and some may even leave the line.

Therefore, the best solution is to keep the checkout just busy enough, without overloading it. We should send customers to the cashier so they have no idle time, but we shouldn’t overload them, causing too long of a queue.

Systems of Flows

In a Queuing system, arrivals enter a system requesting service from a network of finite capacity resources. This models data transmission through computer networks. let’s look at some of the formal notations.

Key variables:

- $\mu$ : Service rate of a resource (1/average service time).

- $\lambda$ : Arrival rate of incoming requests.

- $\rho = \frac{\lambda}{\mu}$ : System efficiency or utilization factor. Stability requires $\rho$ < 1.

- $x = \frac{1}{\mu}$: Average service time

- $t = \frac{1}{\lambda}$: Average time between arrival requests

In Queueing theory we heavily use kendal’s $A/B/K$ notation which specifies:

- $A$: Distribution of inter-arrival times

- $B$: Distribution of service times

- $K$: Number of parallel service resources

For a system with $K$ servers, the total service rate is the number of servers ($K$) x each server service rate ($\mu$) i.e. $K\mu$. So the system efficiency is given by $\rho =\frac{\lambda}{K\mu}$ .

As a refresher, the famous Little’s law says that the average number of customers($N$) waiting in a system is given by the (arrival rate of the customers) x (total turnaround time which includes waiting and service time ). I hope this result is obvious and formally we denote this as:

\[\hspace{3cm} N = \lambda \times T(\rho)\]where $\lambda$ = Arrival rate and $T(\rho)$ is the average waiting time or also called as average response time.

The utilization of a system $\rho$ is given by $\frac{Arrival}{ServiceRate}$. If the $Arrival(\lambda)$ is greater than $Service Rate(\mu)$, we will form queues. The ideal stable queueing system is where on an average the utilization of the system($\rho$) $\le$ 1. This means service rate is equal or greater than the arrival rate. If you ponder for a second, this should come as obvious. Doing some basic algebra, we get the average number of customers in a system ($N$):

\[\hspace{3cm} \rho = \frac{\lambda}{\mu}\] \[\hspace{3cm} \lambda = \rho \times \mu\] \[\hspace{3cm} N = (\rho\mu)\times T(\rho)\]Where:

- $N$ = Average number of customers in system

- $T(\rho)$ = Average response time

- $\mu T(\rho)$ = Response time normalized by service time

- $\rho$ = System utilization.

For network connections, the Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP) is defined as: $Bottleneck Bandwidth \times No Load Delay$. The Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP) captures capacity of an end-to-end network connection path.

In the systems studied:

- Goodness, $G = \rho$

- Badness, $B(G) = Response time = \mu T(\rho)$

The goal of a system is to manage the tradeoff between achieving more Goodness i.e. System utilized and less badness i.e. less delays.

Power Metric

Power metric quantifies the tradeoff between Goodness and Badness from earlier. Specially, Power is defined as:

\[\hspace{3cm} Power = \frac{Goodness}{Badness}\]For data networks, we measure Goodness via throughput i.e. traffic flowing through. Badness is captured by delays from congestion and bottlenecks. So,

\[\hspace{3cm} Power = \frac{Throughput}{Delay}\]Power balances utilization to maximize throughput subject to delay constraints. The optimal operating point is where a small utilization gain causes a sharp delay spike (the “knee”).

This optimization thinking extends to general systems with tradeoffs between desirable outcomes and unfavorable effects. Business examples include profits optimized to costs, productivity tuned to fatigue levels etc. The common principle is maximizing an efficiency ratio.

For data networks, Power neatly captures the utilization-congestion tradeoff.

Deterministic Queueing Systems

A deterministic system is a system in which there is no randomness. This is not something we observe in the real world but it helps to build our intuition.

In case of a $D/D/1$ or $D/D/K$ system:

- $D$: Arrival times is deterministic and happens on a fixed interval.

- $D$: Service times is deterministic and happens on a fixed interval.

- $1$ or $K$: One or K server which service resources.

D/D/1 System

The D/D/1 system models a deterministic arrival process and deterministic service times. Key variables:

- $\frac{1}{\lambda}$ = Exact inter-arrival time between customers

- $\frac{1}{\mu}$ = Exact service time for each customer

- $\rho = \frac{\lambda}{\mu}$ = Utilization factor

For $\rho \le 1$ , customers arrive just as the server becomes free, thus there is no waiting. The response time is simply the service time $\frac{1}{\mu}$.

As $\rho$ approaches 1, the server stays busy nearly 100% of the time while the queue remains empty. This maximizes throughput without delays.

At $\rho = 1$:

- Server utilization is 100%

- Average number in system is N = 1 (1 customer in service, 0 waiting)

- Power is maximized.

Bandwidth ($B$): This refers to the maximum service rate. Since there is 1 server, this is simply equal to $\mu$ (the fixed service rate). No-Load Delay ($D$): This captures the base latency without any congestion. For $D/D/1$, it is the time a customer spends being served without having to wait - which is the fixed service time $\frac{1}{\mu}$.

\[\hspace{3cm} BDP = B \times D = \mu \times (\frac{1}{\mu}) = 1\]However, when $\rho \gt 1$:

- Customers start accumulating in the queue

- Waiting time grows infinitely as queue builds up

- System is unable to keep up with arrival rate.

- Becomes overloaded and unstable.

Therefore, the system breaks down when load exceeds capacity i.e. when $\rho \gt 1$. The optimal operating point is precisely at $\rho = 1$, achieving 100% usage while remaining just under overloaded conditions. This matches the “Keep pipe just full, not fuller” notion and maximum Power.

Here is a simulation where we have a fixed arrival rate of 1 customer per time unit. When the service rate for the customers is faster ($\le 1$), there is no queue as we are servicing customers are they come but when the service rate becomes slower than the arrival rate i.e $\gt 1$, then we see the queue starts getting build up.

There is a nice interactive visualization and simulation of a deterministic system: https://garydmg.github.io/

D/D/K System

The $D/D/K$ system expands the $D/D/1$ system to $K$ parallel identical servers with a deterministic arrival process and fixed service times. Key variables defined as before, along with:

- $K$ = number of servers

- Total service rate (bandwidth) is $K\mu$

- $\rho = \frac{\lambda}{K\mu}$

If $\rho \le 1$:

- An arriving customer is assigned to any available server

- Servers remain 100% busy as customer arrives just as last finishes

- No waiting time.

At $\rho = 1$:

- Input rate $\lambda = K\mu$

- All $K$ servers remain fully utilized.

- Number in system $N = K$.

- Throughput is maximized, delay is minimized

- Bandwidth = $K\mu$, No-load delay = $\frac{1}{\mu}$, Bandwidth-Delay Product = $K$

- Optimum Power point, keeps all servers full but does not overflow

If $\rho > 1$, system overloads as more customers keep accumulating in queue.

So optimal point is $\rho = 1$, $N = K$, matching number of servers. System is fully utilized while remaining just under unstable overload conditions.

Here is a simulation for $D/D/2$ system where we have 2 servers. In this example we have each server which can service a customer in 1 unit of time. As the the arrival rate of the customers increases more than 2, we see the queue length increases and the departure slows down (no more aligned with the red line which represents arrival).

Stochastic Systems

In comparison to deterministic systems, stochastic systems arrivals and/or service times have randomness.

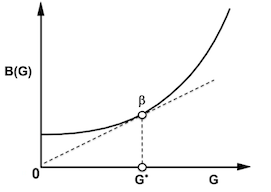

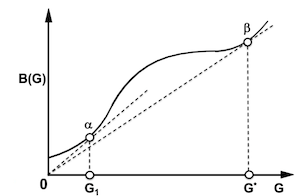

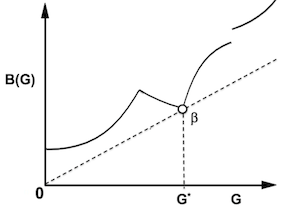

In these systems, unpredictable variability means utilization ($\rho$) cannot be driven as high as in deterministic cases without issues. Random fluctuations cause queues and delays even when average load is less than capacity. To manage the tradeoff between efficiency ($\rho$) and delays $(T(\rho))$, we use the Power function $P(G)$ which we know is the ratio between Good put over Bad put. Here, G is the goodput and $B(G)$ is the badput. Assuming the function $B(G)$ is differentiable, we can differentiate to find the maximum power point.

\[\hspace{3cm} P(G) = \frac{G}{B(G)}\]Assuming $B(G)$ is differentiable and convex, the tangent is where we maximize the Goodput over Badput.

Differentiating P(G) with respect to G:

\[\hspace{3cm} \frac{dP(G)}{dG} = \frac{d}{dG}\left(\frac{G}{B(G)}\right)\]Use the quotient rule for differentiation:

\[\hspace{3cm} \frac{dP(G)}{dG} = \frac{B(G)\frac{dG}{dG} - G\frac{dB(G)}{dG}}{B(G)^2}\]Simplify the derivative of P(G) knowing that $\frac{dG}{dG} = 1$:

\[\hspace{3cm} \frac{dP(G)}{dG} = \frac{B(G) - G\frac{dB(G)}{dG}}{B(G)^2}\]For $P(G)$ to be maximized, the derivative $\frac{dP(G)}{dG}$ must be equal to zero:

\[\hspace{3cm} 0 = \frac{B(G) - G\frac{dB(G)}{dG}}{B(G)^2}\] \[\hspace{3cm} 0 = B(G) - G\frac{dB(G)}{dG}\] \[\hspace{3cm} G\frac{dB(G)}{dG} = B(G)\] \[\hspace{3cm} \frac{dB(G)}{dG} = \frac{B(G)}{G}\]For queueing systems specifically:

- Goodness, G = Throughput/Utilization, $\rho$

- Badness, B(G) = Normalized response time = $\mu T(\rho)$

Therefore, the Power function for queues becomes $P(\rho) = \frac{\rho}{\mu T(\rho)}$ . Maximizing Power balances high throughput $\rho$ with keeping delays $\mu T(\rho)$ in check.

Even for non-convex functon $B(G)$, operating point that gives minimum slope line from origin optimizes Power. If B(G) bounded as G → ∞, maximum Power is finite. Otherwise it grows unbounded.

M/M/1 Queuing Systems

In case of M/M/1 model, we have:

- M: Poisson distribution of arrival times

- M: Exponential distribution of service times

- 1: Single server

Some key attributes:

- Arrivals are random and uncorrelated/

- Service times are memoryless - no correlation between completion times

We know:

- $\mu$ = service rate

- $\rho$ = utilization = $\frac{\lambda}{\mu}$ (arrival rate / service rate)

- $T(\rho)$ = average response time including delays

In case of M/M/1, the average response time $T(\rho) = \frac{1}{\mu-\lambda}$. you can refer here for the derivation Average Network Delay and Queuing Theory basics($T_{q}$ in this post is same as $T(\rho)$).

This gives $\mu T(\rho) = \frac{1}{1-\rho}$. Applying the Power function:

\[\hspace{3cm} P(\rho) = \frac{\rho}{\mu T(\rho)} = \rho(1-\rho)\]Optimizing the power function $P(\rho)$:

- Take derivative with respect to $\rho$

- Set $\frac{dP}{d\rho}=0$ to find optimal $\rho^*$

- This gives $\rho^*$ = 0.5

At optimality:

- $\mu T(\rho^*)$ = 2 (Normalized response time)

- Substitute into Little’s law: $N^* = \rho\mu T(\rho^*) = 1$

- Utilization $\rho^*$ = 50%

So the optimum balances delays vs throughput by keeping 1 customer in system on average. This matches the deterministic case intuition of fully utilizing resources without inducing overflow delays.

M/G/1 Queuing Systems

In case of M/G/1, we have:

- M: Poisson distribution of arrival times

- G: General independent distribution of service times

- 1: Single server

This allows arbitrary service time distributions while keeping arrivals memoryless. Some key attributes:

- $C_{b}$: Coefficient of variation of service distribution. Quantifies variability.

- No closed-form formulas. Analysis requires approximations.

Normalized response time formula:

\[\hspace{3cm} \mu T(\rho) = 1 + \frac{\rho(1+C_{b}^2)}{2(1-\rho)}\]Applying Power function:

\[\hspace{3cm} P(\rho) = \frac{\rho}{\mu T(\rho)}\]Optimizing $P(\rho)$:

- Take derivative $\frac{dP}{d\rho}$ and set equal to 0 gives optimality condition: $\frac{\rho^2(1+C_{b}^2)}{2(1-\rho)^2}$ = 1

- Solving this condition gives $\rho^*$ that maximizes Power.

Plugging optimal $\rho^*$ into Little’s law:

\[\hspace{3cm} N^* = \rho^*\mu T(\rho^*) = 1\]So the optimal number in system remains 1, same as simpler M/M/1 case, even for general service distributions. The key difference vs $M/M/1$ is that optimal utilization $\rho^*$ depends on variability $C_{b}$:

- Lower $C_{b}$ -> higher $\rho^*$

- Higher $C_{b}$ -> lower $\rho^*$

G/M/1 Queuing Systems

In case of G/M/1, we have:

- G: General distribution of arrival times

- M: Exponential distribution of service times

- 1: Single server

Some key attributes:

- Arrival process variability is captured by $C_{a}$ - coefficient of variation of interarrival times

- Service times remain exponential (memoryless).

The Power metric: $P(\rho) = \frac{\rho}{\mu T(\rho)}$

However, G/M/1:

- Lacks closed-form formulas for $\mu T(\rho)$ vs $\rho$

- No clean mathematical optimization

Main results:

- For low arrival variability $C_{a}^2\le 1$

- Includes Erlang arrival distributions.

- Optimized number in system is $0.796 \le N^* \le 1$

- $N^* \approx 1$still holds

- As arrival variability grows very high:

- $N^*$ decreases monotonically to 0

- Therefore, optimization is more sensitive to arrival process than service distribution

- Backing off utilization $\rho$ leaves spare capacity to absorb arrival bursts and delays

- But keeping $N^*$ around 1

In essence, $G/M/1$ mostly maintains the same operating point guidance as $M/G/1$. The Power optimization handles extended randomness by tuning to the variability source while moderately reducing utilization $\rho^*$ closer to saturation levels.

M/M/K Queuing Systems

In case of $M/M/K$, we have:

- M: Poisson arrival process

- M: Exponential service times

- K: Number of parallel servers

Some key attributes:

- Total service capacity = $K\mu$.

- Arriving customer assigned to any available server.

- Utilization $\rho = \frac{\lambda}{K\mu}$

The Power metric: $P(\rho) = \frac{\rho}{\mu T(\rho)}$ Results:

- As $K \to \infty$, limiting behavior $\approx$ deterministic $D/D/1$ system.

- For finite K, optimizing Power gives $N^* \approx K$.

- Almost 1 customer per server on average

- This matches intuition - saturate all servers without overflow

- “Keep pipe just fuller” for higher K.

- For heterogeneous servers:

- $N^* \le K$

- Balances load based on slowest server

So in essence, optimizing multi-server systems scales the single server guidance. Total number in system grows with resources available, while allowing modulation across capacities and randomness sources.

Summary of Queuing Systems

- The overarching conclusion is that optimizing Power closely matches intuitions from deterministic analysis around keeping

- systems fully utilized without inducing overflow delays.

- Mathematically, this manifests in properties like:

- $N^* \approx Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP)$

- $N^* \le Number Of Resources (Servers)$

- For single server queues, optimization keeps average number in system $N^* = 1$.

- Allocates spare capacity to absorb stochastic variability

- For parallel server farms, total $N^* \approx TotalNumberOfServers K$.

- As randomness and dynamics increase, optimization adjusts operating point along this trajectory to tradeoff between efficiency and delays.

- But the fundamental principle remains matching intuitive saturation levels in balance with stochastic fluctuations.

Congestion Control

The concept of optimizing power and traffic flow is highly relevant for managing congestion in computer networks like the Internet.

Key ideas:

- Model an Internet connection pathway as a tandem series topology of links.

- The Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP) generalizes the capacity analogy to connections - bottleneck bandwidth x round-trip propagation delay.

- Optimized traffic keeps packets in-flight across the series chain ≈ BDP.

- Maintains full link utilization without overflow at cramped points.

- The Google BBR (Bottleneck Bandwidth and RTT) congestion control algorithm successfully applies this optimization philosophy.

- BBR uses a model to estimate bandwidth and round-trip delays. Adaptively tunes traffic to target operating points that maximize power along the optimal profile trajectory.

- It outperforms loss-based schemes like Reno, CUBIC that overload buffers and induce excessive queuing delays.

Summary

Here is some of the key points:

- Power Metric: Defined as the ratio of throughput (efficacy) to delay (inefficiency), encapsulating system performance.

- For Single-Server Queues: Optimal operation occurs when there’s, on average, one user in the system.

- In Multi-Server Architectures: The ideal number of active users closely aligns with the number of available servers.

- The concept of “Power” simplifies the complexity of stochastic systems into digestible, deterministic queuing insights.

- This aligns with traditional wisdom that emphasizes the importance of striking a balance between utilization, congestion, and delays.