Notes on Network Signal Congestion Control

“The test of first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” - F. Scott Fitzgerald

All congestion control algorithms try to answer the same question: how fast should data be sent? Traditional protocols like TCP Cubic use just one signal: packet loss to decide. NSCC (Network Signal-based Congestion Control), part of the Ultra Ethernet Transport protocol, uses two signals that work on different timescales. In this post, I’ll try to explain how NSCC works from the first principles, and how it stacks up against familiar protocols.

Before diving in, let’s focus on one key number that shapes everything else. For any window-based congestion control, the main physical factor is the Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP):

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{BDP} = B \times R_0\]Here, $B$ stands for the bottleneck bandwidth, and $R_0$ is the base round-trip time, which is the delay without any queuing. The BDP shows how many bytes can be sent before the first acknowledgment comes back. For example, at 100 Gbps with a 12μs round-trip time, $\text{BDP}$ = 12.5 GB/s x 12 μs = 150 KB. Assuming 4KB size per packet, that is about 37 MTU-sized packets in flight to keep the connection fully used.

Most of what I know comes from three main sources: the UE design paper, the FASTFLOW research paper (which was previously called SMaRTT-REPS), which describes a similar two-signal design and covers details such as control-law formulas, the WTD mechanism, and parameter scaling. I also use the htsim simulator implementation, specifically uec.cpp in the htsim codebase. I am sure I still have a few things wrong, so if you notice any mistakes, please let me know.

1. The Problem: Why Two Signals?

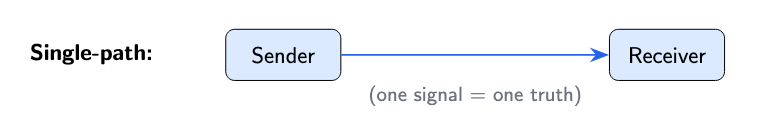

Traditional congestion control assumes a single path between sender and receiver. Every packet sees the same queue, the same delay, the same congestion. If the delay goes up, that is the network state.

When we begin using packet spraying (for reasons outside the current discussion), this single-path assumption no longer holds.

So if Path B is congested but A and C are not, should you lower your sending rate? If you do, you penalize the flow for congestion on just one of three paths and waste most of your available capacity. If you don’t, you ignore real congestion. There’s no clear right answer.

In terms of BDP, at 100 Gbps and 12us RTT, you need 150 KB in flight to fill the pipe. With three paths, each path carries about 50 KB on average. If you reduce the total window because one path has a full queue, you remove bytes from all three paths, even the two that are working well. This causes the flow to fall below its BDP and wastes capacity.

One solution here is to use two signals instead of one. Queueing delay shows the average congestion across all paths. ECN (Explicit Congestion Notification) tells you if this packet’s path had congestion at that moment. Since the sender tracks which entropy value (EV) was used for each packet, it can link the ECN mark to a specific path. Using both signals, you can tell if only one path is congested or if the whole network is overloaded.

A helpful way to understand NSCC is to compare it to a smoke detector and a thermometer:

- ECN works like a smoke detector. It is fast, gives a yes-or-no answer, and can be specific to a path. It tells you that something is wrong, but not how serious it is or exactly where the problem is.

- Queueing delay based on RTT is like a thermometer. It is slower, gives a range of values, and shows how severe the problem is. It tells you how hot the whole building is, but not where the heat is coming from, and it reacts with some delay.

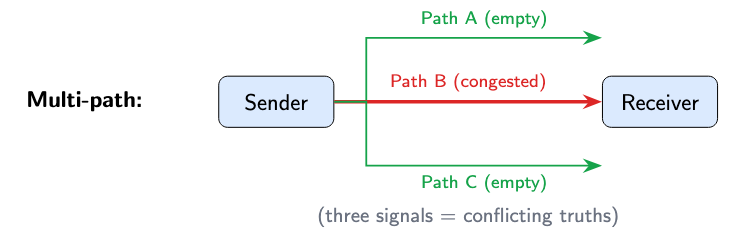

There’s also a crucial difference in when each signal arrives. ECN is a leading indicator because a switch marks a packet as soon as congestion happens. ECN gives a warning right away, before queues get big enough to increase RTT past the target. Delay is a trailing indicator. You only see the delay after the packet has gone through the whole path, been processed, and the ACK comes back. Delay can stay high even after queues start to clear and ECN marks stop.

Neither signal gives the full picture on its own. When we use both together, we get four different responses, which we will look next.

Three Loops, Four Clocks

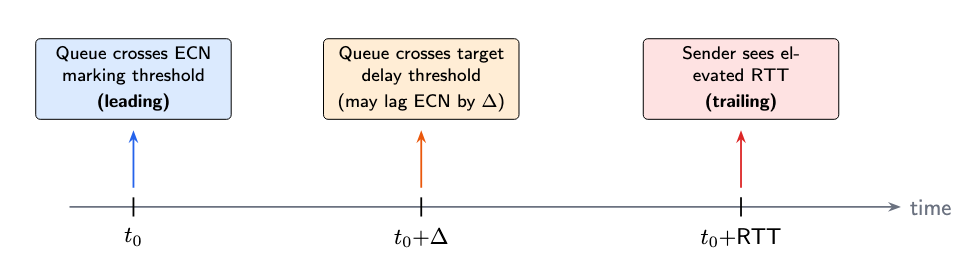

These three loops work across four nested timescales, with each clock running at a different speed from fastest to slowest. To make this clearer, let’s look at each one using the reference setup (100 Gbps, 4 KB MTU, 12 µs base RTT).

Clock 1: Per-ACK. This is the system’s heartbeat, where every ACK triggers a decision. The time between heartbeats depends on serialization delay, which is

how long it takes to send one ACK’s worth of data. For example, assuming 4KB size packets on a 100Gbps link will take about 0.33 µs. If the NIC combines four

packets into one 16 KB delayed ACK, the heartbeat slows to 1.3 µs. Each heartbeat does three things: (1) reads the raw queueing delay and ECN flag

to decide what action to take, (2) feeds the delay sample into the EWMA filter, and (3) accumulates increase credit when the signals say to grow. The action choice

happens instantly, making this the “fast trigger” part of the system.

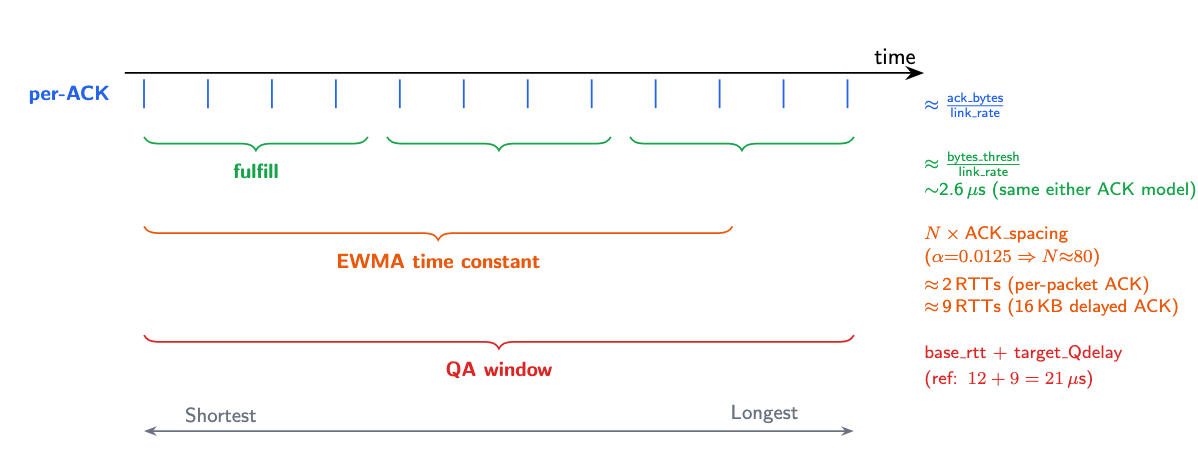

Clock 2: Fulfill. Accumulated increase credits are not applied on every ACK; instead, it batches these actions. A fulfill happens

every time 32 KB of new data is acknowledged. The key detail is that the threshold is measured in bytes, not in ACK counts. With per-packet ACKs (4 KB each), a

fulfill happens every 8 ACKs: 2.6 µs. With delayed ACKs (16 KB each), it happens every 2 ACKs: 2.6 µs. The wall-clock time is the

same in both cases. Using bytes for the threshold makes the fulfill rate independent of the ACK model, which is a deliberate design choice to separate cwnd

growth speed from NIC coalescing behavior.

Clock 3: EWMA convergence. The EWMA filter smooths out raw delay samples using the standard update rule:

\[\hspace{5cm} \texttt{avg_delay} = \alpha \times \texttt{new_sample} + (1 - \alpha) \times \texttt{avg_delay} \qquad (\alpha = 0.0125)\]How quickly does it respond? If the delay suddenly jumps from 0 to a new value V, the old state decays by $(1-\alpha)$ per sample. The usual “one time constant” benchmark is 63% convergence requires

\[\hspace{5cm} (1-\alpha)^N = \frac{1}{e} \quad \Rightarrow \quad N = \frac{-1}{\ln(1-\alpha)} \approx \frac{1}{\alpha} = \frac{1}{0.0125} = 80 \text{ samples}\]Unlike Fulfill, EWMA counts samples, and each sample comes from one ACK, since ACKs are the only way to get delay information. You

cannot sample queueing delay without a returning packet; using a timer would just repeat old data. With per-packet ACKs: 80 × 0.33 µs ≈ 26 µs (~2 RTTs) . With delayed

ACKs: 80 × 1.3 µs ≈ 105 µs (~9 RTTs). The formula is the same, but convergence is four times slower because each combined ACK carries more bytes but still counts as

one delay sample. The filter’s statistical properties are the same in both cases, but its responsiveness in time changes with the ACK coalescing ratio. This design

means the EWMA’s convergence speed is closely tied to the ACK rate.

An important distinction worth making is that, avg_delay does not choose the action. The raw qdelay and ecn flag do that. Instead, avg_delay determines how much to decrease cwnd when

the signals call for a reduction. The EWMA acts as the “slow actuator” that works alongside the fast per-ACK trigger. The htsim simulator uses delayed ACKs (16 KB threshold), which slows EWMA convergence but lowers ACK processing overhead.

Clock 4: QA window. Quick Adapt works on a real-time schedule, firing once every base_rtt plus target_Qdelay. Unlike EWMA, this clock does not count ACKs

or bytes; it uses a wall-clock timer. With htsim defaults: 12 + 9 = 21 µs (FASTFLOW’s 0.5x base target gives 12 + 6 = 18 µs). QA asks a simple question: “Over the

last window, did I send enough data?” If the answer is clearly no, iterative cwnd adjustment is too slow, so QA forces an immediate reset.

Here are the concrete numbers side by side:

Per-packet ACK (4KB) Delayed ACK (16KB)

──────────────────── ──────────────────

per-ACK spacing 4KB/100Gbps ≈ 0.33µs 16KB/100Gbps ≈ 1.3µs

fulfill (32KB threshold) 32KB/4KB = 8 ACKs 32KB/16KB = 2 ACKs

8 x 0.33µs ≈ 2.6µs 2 x 1.3µs ≈ 2.6µs

EWMA 63% (80 samples) 80 x 0.33µs ≈ 26µs 80 x 1.3µs ≈ 105µs

≈ 2.2 x base_rtt ≈ 8.7x base_rtt

QA window: base_rtt + target_Qdelay (0.75 x base_rtt) = 12 + 9(0.75 x 12) = 21µs

FASTFLOW's:base_rtt + target_Qdelay(0.5 x base_rtt) = 12 + 6 = 18µs

If you look at the pattern, fulfill is ACK-model-immune because it shows the same wall-clock time in both columns. EWMA is ACK-model-sensitive, running four times slower with delayed ACKs. QA is ACK-model-independent, using a fixed real-time interval. This happens because each clock uses the units that fit its purpose. Fulfill controls cwnd growth, which should match link capacity in bytes per second. EWMA filters out delay noise, and the delay depends on how many independent samples you gather. QA finds stalls, which are real-time events.

What each clock controls

The key is how these parts fit together: there are many ACK events for each fulfill, many fulfills before the EWMA converges, and just one

QA check per window. This setup creates a “fast trigger, slow actuator” system. The per-ACK signal reacts right away to congestion, while

the EWMA-filtered avg_delay controls how strong the response is. If there is a single bad RTT sample, the system quickly triggers a

decrease (fast trigger), but the size of that decrease is limited by the slower EWMA average (slow actuator). This separation, which is

explained further, keeps the system from overreacting to brief spikes but still lets it respond quickly to ongoing congestion.

Dataflow: what feeds what

Here is the dataflow wiring for a single ACK event. The two signals, delay and ECN, work together to create one of four possible actions. You do not need to focus on the four cases yet; section 2 will explain them from the basics. Use this diagram as a reference to come back to after you have seen the whole process.

ACK arrives

│

├─► raw_rtt ──┬─► base_rtt update (min-tracking)

│ │

│ └─► qdelay = raw_rtt − base_rtt ──┬─► Action choice (is delay high?)

│ │

│ └─► EWMA update ──► avg_delay

│ │

│ (feeds decrease magnitude,

│ NOT action choice)

│

├─► ecn flag ──┬─► Action choice (is path marked?) ──► one of four responses:

│ │ ├─ low delay, no ECN → grow window (fast)

│ │ ├─ high delay, no ECN → grow window (cautious)

│ │ ├─ high delay + ECN → shrink window

│ │ └─ low delay + ECN → reroute only (window unchanged)

│ │

│ └─► Load balancer feedback (path penalties)

│

├─► acked_bytes ──► _received_bytes ──► fulfill trigger (every 32 KB)

│ │

│ └─► cwnd += _inc_bytes/cwnd + η

│

└─► acked_bytes ──► _achieved_bytes ──► QA check (every target RTT; htsim: 21 µs)

│

└─► if achieved < threshold: cwnd reset

2. The Four Quadrants

Let’s build a congestion control algorithm for a spraying network from the ground up. We’ll begin with the simplest method and find out where it fails.

Attempt 1: Use delay only.

We measure the queuing delay on every ACK. If the delay goes above the target, we decrease the window. If it stays below, we increase it. This method works well on a single path, but with spraying, here is what happens:

16 paths total. Path 5 is congested (delay = 20µs).

All other paths: delay ≈ 2µs.

Population average (if you could see all paths at once):

(15 × 2µs + 1 × 20µs) / 16 = 3.1µs → below a 6µs target, fine.

But ACKs arrive one at a time, each from a random path. Individual

samples are either ~2µs (good path) or ~20µs (bad path) — never

3.1µs. Suppose we use a running average of the last 3 samples:

samples: [2, 2, 20, 20, 20, 2, 2, 2] (µs)

avg of 3: — — 8 14 20 14 8 2

With a target of 6µs:

sample 3–5: avg > target → DECREASE

sample 6–8: avg < target → INCREASE

Result: oscillation driven by sampling noise, not real congestion.

The problem is that delay by itself can’t tell you if just one path is overloaded or if the whole network is. If you use a running average that reacts quickly to new samples, it will swing above and below the target whenever you get a group of bad or good path samples. Your RTT samples actually come from a mix of different paths, and no single estimator can clearly separate them.

Attempt 2: Add a second signal: ECN.

ECN marks give us information that queueing delay alone does not. When a switch on a packet’s specific path decides the queue is deep enough, it adds an ECN mark. If we see an ECN mark, we know that this path had a queue above the threshold. If there is no mark, the path stayed below the threshold, but that does not mean there was no queue at all.

Now we have two signals that work together, and each one is binary. ECN is always binary, and delay becomes binary when we set a threshold at target_Qdelay. This creates four possible combinations. Let’s look at the right response for each case.

Definitions

In this context, whenever I mention “delay,” I am referring to queueing delay. This is the extra time packets spend waiting in switch queues, excluding the unavoidable time it takes them to travel across the network.

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{qdelay} = \text{raw_rtt} − \text{base_rtt}\]The base_rtt is the minimum observed RTT and represents the baseline with no congestion. target_Qdelay is the operating point, showing how much queueing the sender is willing to accept. FASTFLOW sets the target RTT at about 1.5 times the base_rtt, which means a target queueing delay of about 0.5 times base_rtt. In case of htsim, it uses slightly higher defaults: 0.75 times base_rtt with packet trimming and 1.0 times base_rtt without. The stricter value from the paper works well when path-aware spraying is active and can quickly reduce load.

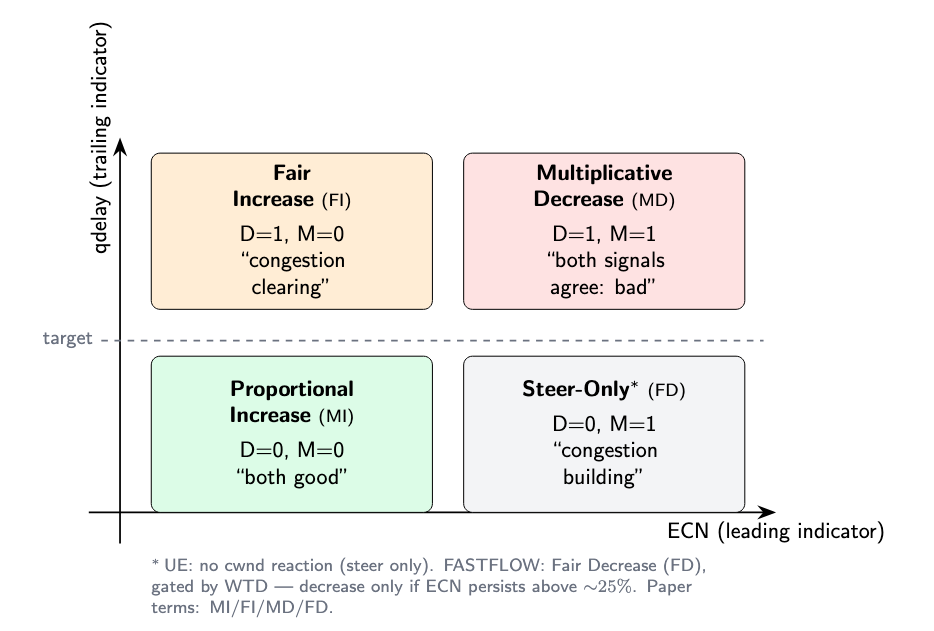

With two binary inputs, delay above or below target ($D$) and ECN mark present or absent ($M$), there are four possible combinations:

Let’s walk through each:

Low delay, no ECN (D=0, M=0): Proportional Increase. Both signals show the network is not congested. Increase the window based on how much we are below the target. The less traffic there is, the more aggressively we increase.

High delay, ECN (D=1, M=1): Multiplicative Decrease. Both signals show the network is congested. Reduce the window based on how much the delay is above the target. The

more severe the congestion, the more we reduce. FASTFLOW recalculates per ACK but limits the decrease to the size of the acknowledged packet, so the window cannot drop

all at once. In case of htsim, it limits this to once per RTT with a 50%. The new_cwnd = cwnd × (1 - severity), where severity = (avg_rtt - target_rtt) / avg_rtt,

bounded to [0, 1). The cwnd drop is bounded to 50% new_cwnd = max(cwnd × (1 - severity), cwnd × 0.5). Both methods adjust proportionally, but the speed of reduction differs.

Low delay, ECN (D=0, M=1): Steer-Only. In this case, ECN marking says congestion is building, but the trailing indicator (delay) hasn’t caught up yet. In a multi-path fabric, this most likely means one specific path is congested while the rest are fine. The response: don’t change the window at all. Instead, tell the multipath load balancer to avoid that path next time. Steer first, throttle second.

This quadrant is where UE, FASTFLOW, and the simulator diverge. UE NSCC explicitly says “NSCC does not react” at the

cwnd level, the load balancer handles it. FASTFLOW adds Wait-to-Decrease (WTD): it tracks an EWMA of ECN-marked ACK fraction, and only applies a

gentle Fair Decrease (proportional to cwnd/BDP) if that fraction exceeds ~25%. Below the threshold, path steering alone handles the congestion,

giving REPS/Bitmap time to fix transient ECMP collisions before CC intervenes. The htsim simulator exposes this as a _q3_pressure parameter:

at 0.0 (default), it matches UE’s pure Steer-Only; at values like 0.05, it applies a 5% per-RTT cwnd decrease.

High delay, no ECN (D=1, M=0): Fair Increase. In this case, Delay is high, but there are no new ECN marks. This usually means congestion is easing. Earlier packets might have been marked, but now the queue is below the marking threshold. The response is to increase the window gently to test if things are getting better. If marks return, we switch to multiplicative decrease right away. If delay stays very high, Quick Adapt acts as a backup.

ECN’s Dual Role: Path Signal AND Rate Gate

One important detail is that ECN has two separate roles in NSCC, both happening on every ACK. First, it acts as a path quality signal for the multipath engine. Each ACK includes the entropy value (EV) that picked the packet’s path, so if an ECN mark appears, it tells the load balancer that this path is congested. Second, ECN acts as a rate gate for the quadrant decision. If ECN is present, the system decreases or uses Steer-Only; if ECN is absent, growth is allowed. In the code, this is managed by a variable called skip, which affects the delay filter.

The dual role is important because, in a multipath network, the path signal gives an escape route. If ECN marks a path, NSCC switches to a better path, so future ACKs are unmarked and proportional increase can resume. The window reduction only lasts until packets are sent on a better path.

In a single-path setup, the path signal does not help because there is no other path to use. Here, the rate gate takes over: ECN keeps blocking proportional increase, so NSCC is stuck with decrease or Steer-Only.

ECN Threshold Calibration

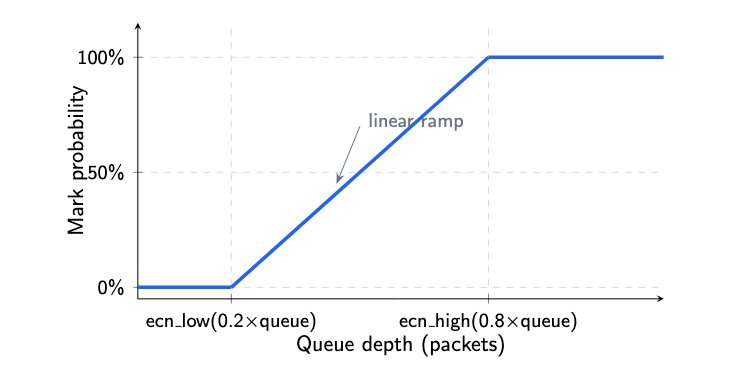

The ECN marks that drive NSCC’s quadrant selection don’t appear by magic — switches generate them when their output queue depth crosses a configured threshold. FASTFLOW (§3.5, ECN Marking) uses RED with Kmin/Kmax as fractions of the switch queue size — 20% and 80%:

ecn_low = ⌈0.2 × queue_pkts⌉ (start marking — "queue is filling")

ecn_high = ⌈0.8 × queue_pkts⌉ (mark everything — "queue is almost full")

Between ecn_low and ecn_high, the switch probabilistically marks packets — the probability ramps linearly from 0% to 100%, RED-style. Above ecn_high, every packet is marked.

These ECN thresholds have a direct impact on the quadrant decision. If ecn_low is set too high, queues can grow a lot before any marks show up. The sender then

stays in proportional increase longer than planned, and by the time marks appear, delay is already high. This can cause the system to jump straight to multiplicative

decrease instead of getting a chance for Steer-Only. On the other hand, if ecn_low is too low, even small, brief bumps can trigger marks, leading to too many

Steer-Only entries even when the network is working well.

3. Window Management: The Control Law

Knowing which direction to move the window is only part of the solution. We also need to figure out how much to move it. NSCC suggests making both the increase and decrease depend on how far we are from the target. In this section, we will build the formulas from the ground up by starting with the simplest method, seeing where it falls short, and improving it step by step until the equations make sense.

3a. Deriving the Increase

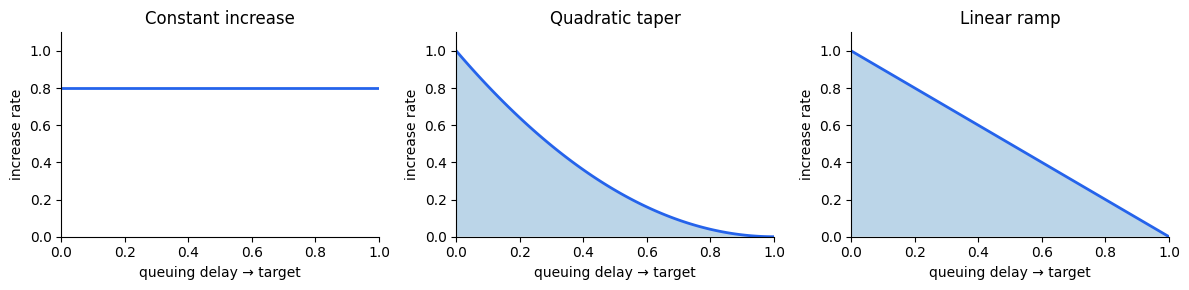

We know we want to increase the window when delay is below the target. But what shape should the increase function have?

Constant increase add the same number of bytes regardless of how far below the target the delay is. The issue is when delay is at 90% of target, we’re almost congested but still pushing just as hard as when the network is empty, resuling in an overshoot. We blow past the target every time.

Quadratic taper increase falls off as delay² approaches target. The issue is that it’s too cautious near zero delay. When the network is nearly empty, the slope is nearly flat, and we barely increase and waste capacity during ramp-up.

Linear ramp increase proportional to (target − delay).

This is the Goldilocks choice:

- Maximum aggressiveness when the network is empty (delay ≈ 0)

- Gentle approach as we near the target (no overshoot)

- Zero proportional increase exactly at the target (the ramp naturally tapers off)

The implementation accumulates increase credits into an _inc_bytes variable on every ACK:

These credits are not applied to the window immediately, they accumulate across multiple ACKs and are applied in batch through the “fulfill” mechanism.

NSCC actually has four increase mechanisms, from most to least aggressive:

- Fast increase triggers when the delay is close to zero, indicating the pipe is almost empty. It grows the window by about 1.25 times per RTT at the reference network speed. This is the fastest way to fill an idle link.

- Proportional increase is the linear ramp described earlier. Growth depends on how much headroom there is: if far from the target, it takes large steps; if near the target, it takes small steps; at the target, growth stops. This is the main method used during steady operation.

- Fair increase is a constant additive increase, similar to TCP’s linear growth. It is used when there is high delay and no ECN, a situation where congestion is easing but caution is still needed.

- Eta is a small liveness floor added at every fulfill, even during Steer-Only or multiplicative decrease. It keeps the window slowly increasing to prevent permanent starvation, but does not interfere with the congestion signal.

3b. Deriving the Decrease

With multiplicative decrease (D=1, M=1), using a fixed percentage cut like the TCP approach of always cutting by 30% does not consider how severe the congestion is.

If the delay is just above the target, this method overreacts. If the delay is ten times the target, it does not react enough. NSCC instead computes a proportional

cut. We want a severity factor s that controls how much of the window to cut:

Requirements for $s$:

- $s = 0$ when $R = R_\text{target}$, no cut at the boundary

- $s \to 1$ as $R \to \infty$, maximum cut under extreme congestion

- $0 \le s \le 1$, the cut fraction is always bounded

where $R$ is the measured RTT and $R_\text{target} = R_0 + \text{target}_{Qdelay}$ is the target RTT ($R_0$ = base RTT).

The natural choice is to define $s = (R - R_\text{target}) / R$. This gives:

- At $R = R_\text{target}$, $s = 0$

- As $R \to \infty$: $s \to 1$

- For $R \ge R_\text{target}$, $s \in [0, 1)$

Putting it all together:

\[\hspace{5cm} W_\text{new} = W \times \left(1 - \gamma \cdot \frac{\texttt{avg_rtt} - R_\text{target}}{\texttt{avg_rtt}}\right)\]The default value of $\gamma = 0.8$ allows for a quick response while staying within limits. Because the severity factor $s = (R - R_\text{target})/R$ always falls between 0 and 1, the largest possible cut is $\gamma \times 1 = 0.8$, meaning at least 20% of the window is kept.

In the simulator variant (htsim uec.cpp), there is a minimum kept fraction of 0.5, so no more than half is cut in any step. The decrease is also limited to once

per base RTT using _last_dec_time.

if (eventlist().now() - _last_dec_time > _base_rtt) {

// allowed to decrease

new_cwnd = cwnd × (1 - γ × s)

new_cwnd = max(new_cwnd, cwnd × 0.5) // 50% floor

_last_dec_time = eventlist().now()

} else {

// too soon, skip this decrease

}

What happens if we change the gamma parameter? To make this clearer, let’s look at how the kept fraction changes at different RTT levels, using multiples of the target RTT.

At RTT = 1.5 x target_RTT:

γ=0.5: kept = 1 − 0.5x(0.5t)/1.5t = 1 − 0.17 = 83% (gentle)

γ=0.8: kept = 1 − 0.8x(0.5t)/1.5t = 1 − 0.27 = 73% ← NSCC default

γ=1.0: kept = 1 − 1.0x(0.5t)/1.5t = 1 − 0.33 = 67%

At RTT = 2 x target_RTT:

γ=0.5: kept = 1 − 0.5x(1.0t)/2.0t = 1 − 0.25 = 75%

γ=0.8: kept = 1 − 0.8x(1.0t)/2.0t = 1 − 0.40 = 60% ← NSCC default

γ=1.0: kept = 1 − 1.0x(1.0t)/2.0t = 1 − 0.50 = 50% (hits floor)

At $\gamma = 0.8$, moderate congestion (1.5x target RTT) leads to a 27% cut, which is significant but not drastic. Severe congestion (2x target RTT) results in a 40% cut, which is aggressive but still above the 50% floor. The floor only comes into play at extreme congestion.

One important detail is that the decrease formula uses the EWMA-filtered average RTT (avg_rtt), not the raw per-packet RTT. For example, a single packet might hit a

temporarily full queue and show 3x the target RTT, but if the filtered average is only 1.2x, the actual cut will be mild. This follows the “fast trigger, slow actuator”

pattern: the algorithm enters the decrease quadrant quickly by using raw delay for the decision, but adjusts the cut size more slowly by using the filtered RTT.

3c. Batched Increases, Immediate Decreases

NSCC applies increases and decreases asymmetrically:

- Decreases are immediate. When the signals say “cut,” the window shrinks on that ACK. You want to react to congestion quickly.

- Increases are batched. Each ACK accumulates increase credit into

_inc_bytes. When a total of ~32 KB has been acknowledged (the “fulfill” threshold), the credits are applied all at once. You want to grow cautiously.

When the fulfill fires, the accumulated credit is applied as:

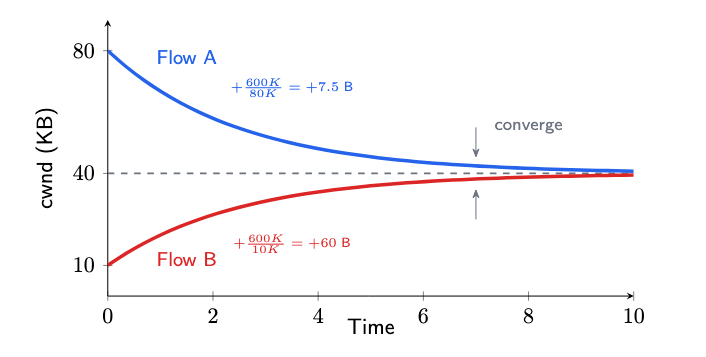

cwnd += _inc_bytes / cwnd

That division by cwnd is the fairness mechanism. Two flows sharing a bottleneck experience the same delay and accumulate similar _inc_bytes over one RTT. But the step

each flow actually takes depends on its current window size:

Flow A (large window) divides by 80 KB → small step. Flow B (small window) divides by 10 KB → large step. The small flow catches up, the large flow slows down, and

they converge. This is mathematically equivalent to TCP’s classic +MSS²/cwnd additive increase.

Over one RTT, total acked_bytes ≈ cwnd (you acknowledge roughly one window’s worth of data). Substituting into the fulfill formula:

- Proportional:

_inc_bytes ≈ alpha x cwnd x (target − delay)→cwnd += alpha x (target − delay) - Fair:

_inc_bytes ≈ fi x cwnd→cwnd += fi

The cwnd terms cancel out. The per-RTT step is based on headroom for proportional control or a fixed probe size for fair control, rather than the flow’s window size. Two flows with different window sizes but the same headroom will take the same absolute step per RTT. This is the convergence property we are aiming for.

4. The Delay Engine

The control law we discussed earlier relies on two types of delay: a raw per-packet delay for the quadrant decision and an EWMA-filtered average for the decrease magnitude. In this section, we explain how the delay engine provides both, starting from zero-point calibration and using a three-case filter to help NSCC handle multi-path noise.

4a. Base RTT: The Zero Point

Every thermometer has a zero point. For NSCC, this zero point is base RTT, which is the round-trip time a packet would see if all queues along its path were empty.

measured_rtt = base_rtt + queuing_delay

──────── ──────────────

"zero" "the signal"

If base RTT is incorrect, all delay measurements will be off, and every decision based on them will be flawed. If it is set too high, the algorithm underestimates congestion and becomes too aggressive. If it is too low, it overestimates congestion and acts too cautiously.

Base RTT is not set by the user. According to UE’s NSCC, the sender keeps “a value representing its best guess of the expected unloaded RTT at any moment.” RTT measurement should leave out receiver service time so the signal reflects only network delay.

Simulator modeling assumption (htsim): The simulator computes base RTT deterministically from the topology by summing three physical components: round-trip propagation delay across every hop, data packet serialization time per hop, and ACK serialization time on the return path. It offers two modes: Global mode (the default) uses the worst-case diameter-spanning RTT for all flows, conservative for short-path flows but safe. Per-flow mode uses the actual hop count between each source-destination pair, giving accurate base RTTs for heterogeneous traffic. This deterministic computation is a simplification, real deployments would need to measure base RTT dynamically (as FASTFLOW discusses: either pre-computed per hop-count class or measured Swift-style from the lowest recent samples).

During operation, base RTT is typically refined downward as the flow observes actual RTT samples. If the topology estimate was 12 µs but the first few packets measure 9.3 µs on an uncongested path, base RTT tightens to 9.3 µs and BDP/maxwnd are recalculated immediately.

Why primarily min-tracking? If base RTT could freely increase, a burst of congestion would raise the baseline, making the algorithm think “this higher RTT is normal.” It would underestimate queuing delay for subsequent packets, becoming less responsive precisely when it should be more responsive. Min/low-percentile tracking (using the best RTT samples observed) avoids this failure mode. However, pure monotonic-decrease has its own risks: route changes or path reconfigurations can legitimately increase the true unloaded RTT. FASTFLOW notes that base RTT can be either pre-computed at fabric setup (once per hop-count class) or recomputed dynamically. Practical implementations may need a slow upward drift mechanism to handle genuine topology changes, though this must be carefully guarded against congestion-induced inflation.

This matters beyond just the delay signal. Base RTT propagates into many subsystems: BDP calculation, maximum window cap, Quick Adapt timing, probe scheduling, and even the EWMA filter’s trust model. An inaccurate base RTT has cascading effects.

4b. Target Delay

Base RTT sets the starting point, and queuing delay acts as the signal. But how do we know when queuing delay becomes too high? The target delay (target_Qdelay) answers this by setting the threshold that separates low delay from high delay in the quadrant matrix.

There are some differences between the paper and the actual implementation. The simulator uses three levels of priority: first, it uses an explicit CLI parameter if one is set; second, it uses 0.75 times base_rtt when packet trimming is available; and third, it uses 1.0 times base_rtt if trimming is not available. The higher default values in the simulator give a wider safety margin when there is no active path-aware spraying. The 0.75 factor with trimming is intentional because trimming gives fast, reliable feedback, trimmed packets become NACKs instead of being silently dropped,so the algorithm can use a tighter target without risking underuse during recovery.

Target delay is more than just a threshold; it is the balance point for the proportional control loop. The increase ramp described in §3a naturally leads to a state where queuing delay stays close to the target. As the delay gets closer to the target, growth slows down, and if the delay goes above the target, growth becomes negative through Fair Increase or Multiplicative Decrease.

The math reveals an interesting result. The proportional increase rate, alpha, is defined as:

\[\hspace{5cm} \alpha = \frac{4 \times \text{MSS} \times \text{scale_a} \times \text{scale_b}}{\text{target_Qdelay}}\]And scale_b is defined as target_Qdelay / reference_rtt. Substituting:

\[\hspace{5cm} \alpha = \frac{4 \times \text{MSS} \times \text{scale_a} \times \text{target_Qdelay}}{\text{reference_rtt} \times \text{target_Qdelay}}\]Since target_Qdelay is in both the numerator and denominator, it cancels out, leaving:

\[\hspace{5cm} \alpha = \frac{4 \times \text{MSS} \times \text{scale_a}}{\text{reference_rtt}}\]Alpha does not depend on target_Qdelay. This means that changing the target only affects where the algorithm settles, not how quickly it gets there. To understand

this, remember the proportional increase formula from §3a: inc_bytes += alpha × acked_bytes × (target − delay). Alpha sets how quickly the window grows for each

microsecond of available space, while the target sets the point where growth stops. It is similar to adjusting a thermostat: raising the setpoint from 70°F to 75°F does

not make the heater stronger—the room just settles at a different temperature at the same rate. Because scale_b cancels out the target, operators can adjust the

queueing target without affecting how the algorithm converges.

4c. Two Delays, Two Jobs

This is the ‘fast trigger, slow actuator’ pattern from Section 1, explained in more detail. Earlier, we saw that raw queue delay decides when to act, while the EWMA-filtered average delay determines how much to decrease. Here’s why separating these roles matters.

What happens if you don’t separate them? Suppose you use raw delay for both decisions. If a packet hits a briefly full queue and comes back with three times the target delay, you correctly decide to decrease (since ECN plus high delay is a real signal) and make a large cut based on that severity. But this was just one packet on one path. When the next packet returns to normal, you switch to increasing, and the system starts to oscillate.

How does the split help? The same packet still causes an immediate decrease because the raw delay says to act now. However, the size of the cut is based on the EWMA-filtered average, which is only 1.2 times the target since most recent packets were normal. This way, the system responds quickly but makes a gentle adjustment, staying responsive without overreacting.

| Decision | Which delay? | Speed |

|---|---|---|

| “Should I act?” — action choice | Raw per-packet qdelay |

Instant (this ACK) |

| “How hard?” — decrease magnitude | Filtered avg_rtt = base_rtt + avg_delay |

Slow (~80 samples) |

4d. Three-Case EWMA with Trust Bias

§1 (Clock 3) showed that the EWMA filter ($\alpha = 0.0125$, about 80 samples to reach 63%) is intentionally slow. It smooths out short-term per-path noise so that only ongoing congestion causes a decrease in magnitude. However, just being slow is not enough. In a spraying fabric, some delay samples are less reliable than others, so the filter must take this into account.

The main idea is that ECN serves as a trust signal for delay samples. In the code, the ECN echo flag appears as a variable named skip, where skip = true means ECN is present. The outer if statement checks for the no-ECN discount case first, giving it the highest priority:

if (!symmetric && skip == false && delay > target_Qdelay)

avg_delay = α × base_rtt × 0.25 + (1−α) × avg_delay // discount

else

if (delay > 5 × base_rtt)

avg_delay = r × delay + (1−r) × avg_delay // emergency (r pinned at 0.0125)

else

avg_delay = α × delay + (1−α) × avg_delay // normal

The branching priority produces four cases:

Condition What filter sees Rationale

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

No ECN + low delay actual delay (α) Trusted. Below target,

no congestion signal.

No ECN + high delay base_rtt × 0.25 (α) Discounted. High delay

(including extreme) without ECN → likely path

noise. Don't inflate avg.

ECN + moderate delay actual delay (α) Trusted. ECN confirms the

congestion is real.

ECN + extreme delay (> 5× base) actual delay (α*) Emergency. ECN confirms

it's real. *Code uses a

hardcoded r = 0.0125 — same

value as α today, but pinned

so a future α retune can't

destabilize this path.

The discount case is especially important because it applies most broadly. Since the outer if statement runs first, all high-delay samples without ECN are discounted, even the extreme ones. High delay without ECN is suspicious. In a 16-path fabric, it likely means one path hit a temporary queue while the other 15 paths are unaffected. If this raw delay were fed into the EWMA, it would raise the average and make the next multiplicative decrease too large. Instead, the filter uses base_rtt × 0.25 as a small adjustment. This approach recognizes that something happened but does not fully trust the sample. Only when ECN confirms congestion (skip = true) does the actual delay get used.

The emergency case only happens when ECN is present. If ECN confirms that the network is congested and the delay is extremely large (greater than 5x base_rtt, which could indicate a failing link or a major routing change), the filter accepts the real sample but uses a fixed r = 0.0125 instead of the usual $\alpha$. Right now, both values are the same, but this hardcoding is a safeguard. If someone changes $\alpha$ for another fabric later, the emergency path will still use its conservative rate.

4e. RTT Sample Validation

Not every ACK gives a usable RTT sample. For each packet, the sender keeps track of two things: _rtx_times, which counts how many times the packet has been sent, and rtx_echo, a bit from the receiver that shows if the packet was marked as a retransmission. The validateSendTs function checks these to decide if the sample should be used.

Rule 1: rtx_times = 0 AND rtx_echo = false → VALID (fresh packet, clean ACK)

Rule 2: rtx_times = 1 AND rtx_echo = true → VALID (one retransmit, receiver confirms)

Rule 3: anything else → INVALID (skip sample, use avg_delay)

Rule 1 is the ideal case: the packet is sent once and acknowledged once. Rule 2 handles the usual trim-retransmit situation, where there is

one retransmit after a NACK, and the receiver confirms it got the retransmit. In this case, RTT is measured from the retransmit timestamp. Rule 3 rejects all

other cases, such as multiple retransmits (rtx_times ≥ 2) or when the send count and the echo do not match, for example, if the sender retransmitted but the

receiver got the original. Invalid samples are ignored, and the EWMA keeps using the current avg_delay.

5. Quick Adapt: The Emergency Brake

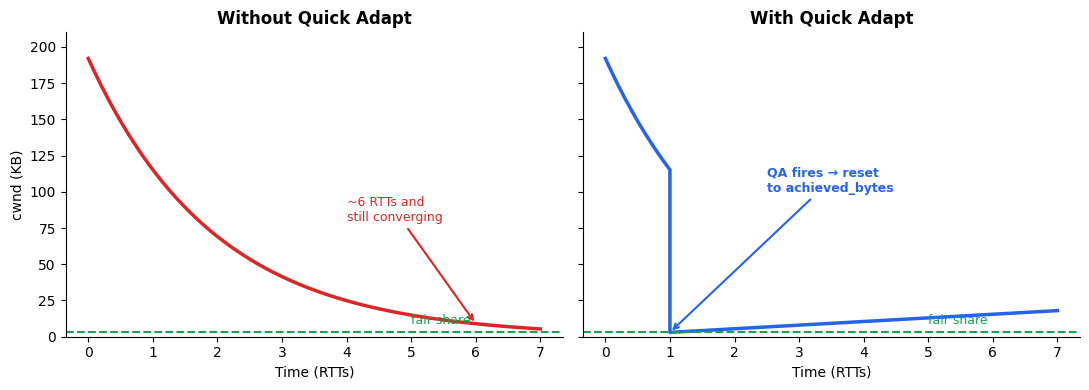

Normal multiplicative decrease works in steps. For example, in a 64-flow incast, each flow’s fair share is about 1/64 of the total bandwidth. Even if the window is halved every round-trip time, it still takes about $\log_2(64) \approx 6$ RTTs to converge. During these 6 RTTs, extra packets can build up and cause heavy queuing for all flows.

Quick Adapt takes a different approach. Instead of just lowering the window, it resets the window to the amount that was actually delivered in the last measurement period. This way, the window matches what the network can really support, rather than making gradual changes.

Dual Guards: Preventing False Positives

QA uses a measurement window that lasts as long as base_rtt + target_Qdelay. This period is long enough to get a complete feedback cycle. At the end of each

window, QA checks two conditions, and both must be true:

- Something bad is happening. A NACK was received, or loss was detected, or the delay exceeded 4 x target_Qdelay.

- The flow is severely underperforming. Achieved bytes in the measurement window are less than maxwnd » qa_gate, with the default qa_gate = 3, that’s less than 12.5% of the maximum window.

Both conditions have to be true at once. If a flow is only moderately congested, like having high delay but still delivering half of maxwnd, QA does not activate. In these cases, normal multiplicative decrease is enough. QA only steps in when the flow is nearly stalled.

Stale Feedback Suppression

After QA activates, packets already in the network still carry old feedback. Their RTT samples and ECN marks show the previous congestion state, before QA reduced

the window. To handle this, QA sets _bytes_to_ignore equal to _in_flight, which is the number of bytes currently in the network. ECN-marked ACKs (skip=true)

increase a counter, and as long as this counter is below _bytes_to_ignore, congestion control updates from these ACKs are ignored. Non-ECN ACKs are still

processed, since they reflect the new, post-QA window. This stops old ECN marks from further shrinking the window after QA has already fixed the problem. Once

these old ACKs are gone, the flow returns to normal and ramps up from its new baseline using proportional increase.

6. SLEEK: Loss Recovery for Spraying Fabrics

Why 3-DupACK Fails

TCP detects packet loss by looking for three duplicate ACKs. If you get three ACKs for the same sequence number, it likely means a packet was lost. This method works well when packets follow a single path and arrive in order. When packets are sprayed across multiple paths like 8 paths with different delays, packets often arrive out of order. If you use a fixed threshold of 3, loss recovery would trigger all the time, even on healthy flows. The threshold should adjust based on how much reordering you expect.

TCP (single path): NSCC (sprayed):

Sent: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Sent: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Recv: 1, 2, _, 4, 5 Recv: 3, 1, 5, 2, _

↑ gap = loss! ↑ reordering is NORMAL

TCP: 3 dupACKs → retransmit TCP: would trigger false retransmits

on EVERY flow, EVERY RTT

SLEEK’s Scaled Threshold

SLEEK, which is the loss recovery mechanism used in NSCC’s simulator, replaces the fixed threshold with one that scales with the window size. The out-of-order count (ooo) keeps track of how many packets have arrived out of order, so the threshold is also measured in packets.

threshold_pkts = min(1.5 x cwnd, maxwnd) / pkt_size

The code first calculates the threshold in bytes using min(1.5 x cwnd, maxwnd), then divides by the average packet size to get a packet count for comparing with ooo. For

example, with a 600 KB window and 4 KB packets: min(1.5 × 600KB, 1000KB) / 4KB = 225 packets can be out of order before loss recovery starts. The 1.5 multiplier is a

tuned constant called loss_retx_factor. Making the threshold proportional to cwnd means it scales with the flow’s sending rate. Larger windows can handle more

reordering before declaring a loss.

How Recovery Works

runSleek runs on every ACK and takes two inputs: ooo, which is the out-of-order packet count, and cum_ack, the highest contiguously received sequence

number. It also uses _tx_bitmap, a map of all packets sent but not yet ACKed. During normal operation, if ooo is below the threshold, the function returns right away. There is nothing else to do.

Entering recovery happens when ooo goes over the threshold. At this point, SLEEK takes a snapshot by setting _recovery_seqno to _highest_sent. This marks a boundary: everything below this point is considered “old” and might be lost, while everything above is “new” and was sent after the issue was found. Recovery focuses only on old packets.

Sent: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

ACKed: 1 2 4 5 7 8 ← cum_ack = 2 (contiguous)

In bitmap: 3 6 9 10 ← sent but not ACKed

Recovery snapshot: _recovery_seqno = 10

Scan from cum_ack (2) to recovery_seqno (10):

seq 3: in bitmap → queue for retransmit

seq 4: not in bitmap (ACKed) → skip

seq 5: not in bitmap (ACKed) → skip

seq 6: in bitmap → queue for retransmit

seq 7: not in bitmap (ACKed) → skip

seq 8: not in bitmap (ACKed) → skip

seq 9: in bitmap → queue for retransmit

Finding the gaps means SLEEK scans sequence numbers starting from cum_ack and moving upward, looking for missing packets. For each number, it checks if the packet is still in _tx_bitmap. If it is, the packet was sent but never ACKed, so it is missing. If it is not in the bitmap, the receiver already ACKed it out of order, so it can be skipped. Any missing packets are queued for retransmission.

Pacing the retransmits means the scan does not go all the way to _recovery_seqno at once. Instead, it is limited to one cwnd’s worth of packets per call. As the receiver ACKs retransmitted packets and cum_ack moves forward, later calls scan further into the range. This approach prevents a burst of retransmits from flooding the network.

Exiting recovery happens when, on each call, runSleek first checks if cum_ack is greater than or equal to _recovery_seqno. If the cumulative ACK has moved past the snapshot, all old packets have been handled, either received out of order or retransmitted and received. At this point, recovery is complete.

Probes and RTO

SLEEK also uses explicit probes, which are packets that ask the receiver, “did you receive everything I sent?” If a probe ACK comes back quickly, it means the network path is clear and missing packets are truly lost, not just delayed in queues. If a probe shows a high delay, it is less clear,missing packets might still be on the way. But a fast probe is a strong sign that anything still missing is gone for good.

Under SLEEK is the oldest safety net in transport protocols: the Retransmission Timeout (RTO). The minimum RTO is based on the physical worst case, which is the time needed to drain a full queue at every hop along the longest path.

min_rto = 15µs + queue_drain_per_hop × diameter_hops

For a typical 100 Gbps, 3-tier fat-tree: 15µs + 50µs × 6 = 315µs, roughly 25x the base RTT. This is deliberately very conservative. In a spraying network, path latency variance is high (packets on different paths can experience very different delays), so a tight RTO would fire frequently on healthy flows. RTO is the last resort, not the first.

When a flow is stuck, cwnd is too small to retransmit, and no receiver credit is available, the RTS (Request-To-Send) mechanism sends a header-only packet to request credit from the receiver. This prevents deadlock when both cwnd and credit are exhausted. RTS is rate-limited to one per RTT to prevent RTS storms after widespread loss events.

The Recovery Hierarchy

The three mechanisms form a speed-ordered stack:

| Mechanism | Speed | Trigger | When it dominates |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLEEK | ~1 cwnd of OOO | OOO count > 1.5 × cwnd | Normal path: detects loss in-band |

| Probes | base_rtt + target_Qdelay | Probe ACK with low delay | Stalled flows with no OOO signal |

| RTO | ~315 µs | Complete silence | Total loss: nothing coming back |

Fast mechanisms handle common cases, while slower mechanisms handle rare situations. This layered approach helps avoid the false positives that can occur with TCP’s fixed threshold while still providing a safety net for real failures.

7. Multipath: Steer First, Throttle Second

The Steer-Only quadrant makes sense when we understand how it works with the load balancer. Here is how the process works:

1. Packet sent on Path 5, gets ECN-marked at a congested switch

2. ACK arrives: ecn=true, delay=3µs (low — other paths are fine)

3. Quadrant: ECN + low delay → Steer-Only (cwnd unchanged)

4. Multipath engine: Path 5 penalized

5. Next packet routed to Path 6 instead

6. Path 6 ACK: no ECN, low delay → proportional_increase → cwnd grows

As a result, the flow kept its sending rate and avoided the congested path, so no throughput was lost. This follows the “steer first, throttle second” idea: path steering is the first step, and window reduction is the backup.

How Path Selection Works

So far, we have said things like “multipath engine: Path 5 penalized” without explaining how paths are tracked and penalized. In UE, each packet has an entropy value (EV) that decides its physical path through the network using ECMP hashing. ACKs send the EV back to the sender, along with any ECN marks or trim NACKs. This makes ECN a path-specific signal. The multipath engine uses this feedback, linked to the EV, to decide which paths to avoid.

The simulator (htsim) uses four path-selection strategies. REPS is explained in the UE design paper, which describes how it uses EVs returned in ACKs, and comes from earlier SMaRTT-REPS work. The current FASTFLOW paper talks about adaptive load balancing in general, without focusing on REPS. The other strategies are specific to the simulator. The Bitmap strategy is the most illustrative, as it keeps a penalty score for each EV or path:

Cycle 1: Path scores [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] → all paths available

Send on: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Feedback: Path 3 gets ECN, Path 7 gets NACK

Cycle 2: Path scores [0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0] → skip paths 3, 7

Send on: 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 1, 2

Feedback: Path 3 penalty decays, Path 7 gets another NACK

Cycle 3: Path scores [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0] → skip only path 7

Send on: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 1

The four strategies for increasing sophistication:

- Oblivious: This strategy uses round-robin across paths with a random XOR permutation. It does not use feedback and simply rotates through paths in a set order. It works well when all paths are the same.

- Bitmap: This strategy assigns a penalty score to each EV. If an EV gets ECN, NACK, or timeout feedback, its penalty increases. EVs with penalties are skipped when selecting paths. Penalties decrease over time, so paths that were briefly congested can be used again.

- REPS: Recycled Entropies for Path Spraying. This method uses a circular buffer to track the quality of each EV. Good EVs, which get clean ACKs, are reused. Bad EVs are taken out of the rotation.

- Mixed: This is a hybrid of Bitmap and REPS. It combines penalty-based avoidance with path recycling.

Paths with penalties are skipped when selecting routes. As penalties decrease over time, paths that were briefly congested can be used again. This is the other part of the Steer-Only quadrant: the congestion control does not change the window, but the multipath engine steers traffic away from the busy path.

Last-Hop Detection: Not All Trims Are Equal

NACK processing in the multipath engine is more detailed than it first seems. It identifies where the trim happened

Last-hop trim (receiver NIC):

────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Sender ──→ Switch A ──→ Switch B ──→ [Receiver NIC ✗]

↑ trim happened HERE

The fabric path was fine! Only the receiver port is congested

(e.g., incast at the receiver).

→ Multipath feedback: path is fine (no penalty)

Mid-fabric trim (switch):

────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Sender ──→ [Switch A ✗] ──→ Switch B ──→ Receiver

↑ trim happened HERE

The fabric path itself is congested.

→ Multipath feedback: penalize this path

Why this matters: without last-hop detection, every trim would penalize the fabric path, even when the real bottleneck is a receiver-side incast that path steering cannot fix. The Bitmap strategy would waste penalty budget on innocent paths, and REPS would remove good entropies from its recycle buffer. Last-hop detection keeps the path quality signal clear, so the multipath engine only penalizes paths that actually caused the problem.

Steer First, Throttle Second

When ECN marks arrive with low delay, the sender doesn’t know why. It could be an ECMP collision on one path (fixable by steering to a different path) or the very beginning of global congestion (which requires a cwnd cut). The simulator’s answer is Q3, the Steer-Only quadrant. When the sender sees ECN + low delay, Q3 makes no window change. The multipath engine penalizes the marked path and steers future packets to other paths. If that resolves the congestion, clean ACKs return, and the flow continues at full rate. If it doesn’t, delay rises above target, ACKs shift to Q2 (multiplicative decrease), and cwnd reduction kicks in.

The “wait” is built into the system: there is no timer or gate, just a gap in the quadrant matrix where no decrease action happens. The wait continues until the delay increases, usually by 1 or 2 RTTs.

When This Works and When It Doesn’t

Whether Q3’s “steer first” approach works depends on whether path steering can solve the problem:

Scenario 1: ECMP collision (path steering can fix it)

t=0µs Two flows collide on Path 3 (ECMP hash collision)

t=2µs ECN marks arrive, delay still low

→ Q3 fires: cwnd unchanged

→ Multipath engine penalizes Path 3

t=4µs Next packets routed to Paths 4, 5 instead

t=6µs Clean ACKs arrive: no ECN, low delay

→ Q1 (proportional increase): cwnd grows

t=8µs Path 3 penalty decays, collision resolved

Result: zero throughput lost. Steering resolved it in ~1 RTT.

Scenario 2: Receiver incast (path steering cannot fix it)

t=0µs 64 flows converge on one receiver port — ALL paths congested

t=2µs ECN marks + HIGH delay on every path

→ Q2 (multiplicative decrease) fires — delay is above target

t=4µs Still congested. MD cuts ~40% per RTT... but fair share is 1/64

t=12µs After several RTTs, still far above fair share

→ Quick Adapt fires: cwnd reset to what the network actually sustained

t=14µs Flow ramps up from new baseline

Result: Q3 never engaged (delay was always high from the start).

MD was too slow for this degree of contention; QA provided the reset.

The three mechanisms form a response hierarchy: steer → throttle → emergency reset. For ECMP collisions, steering alone resolves them. For global congestion, delay rises, and a multiplicative decrease kicks in. If even that converges too slowly, Quick Adapt provides the backstop.

Single-Path Limitation

The “steer first” philosophy assumes there are alternative paths to steer to. On a single-path topology, Q3 becomes counterproductive: ECN correctly indicates congestion on the only path, but Q3 does nothing with it. The flow only reduces its window when the delay exceeds the target (transitioning to Q2), resulting in a delay in reaction compared to a protocol like TCP Cubic, which responds to every ECN mark. Q3 is unconditionally a NOOP regardless of how many marks arrive, there is no adaptive fallback.

8. Transport Feedback

Earlier sections explained what NSCC decides. Here, we look at how the timing of those decisions is controlled, like when ACKs arrive to trigger the next step.

Delayed ACKs: Three Triggers

The simulator uses three triggers for delayed ACKs: ECN-immediate ACKs, byte-threshold batching, and AR flag use. Other systems might combine ACKs differently. The receiver does not send an ACK for every packet. Instead, it collects received bytes and sends an ACK when one of three conditions happens:

- If a packet is ECN-marked, the receiver sends an ACK right away. The sender needs this signal quickly to respond correctly. Delaying this ACK would make ECN less useful as an early warning.

- When the byte threshold is reached (by default, 16 KB or about 4 MTUs), the receiver sends an ACK. This usually means about four packets are acknowledged at once, which helps reduce ACK overhead.

- If the ACK Request (AR) flag is set, the sender is asking for an ACK. This flag is used on the last packet in the backlog or when the next packet will reach the cwnd or credit limit. It helps prevent deadlock.

The AR flag is crucial for the sender to avoid a subtle deadlock. Without it:

Without AR: With AR:

───────────── ─────────────

Sender: send pkt 7, pkt 8 Sender: send pkt 7, pkt 8 (AR=true)

cwnd full, wait... cwnd full, wait...

Receiver: 8KB < 16KB threshold Receiver: AR flag → ACK immediately!

waiting for more data Sender: ACK arrives → cwnd opens

... → send pkt 9, 10

(deadlock) → flow continues

Feedback Timing Chain

The total feedback loop, from send to quadrant decision, is roughly one RTT plus any ACK delay. ECN-marked packets get the fastest feedback (ACKs are immediate), which is exactly right: the “smoke detector” signal should arrive as quickly as possible. Non-ECN packets may wait up to 4 packets for batching, adding a few microseconds of delay that the slow EWMA filter easily absorbs.

Data packet sent

│

│ serialization (NIC) + propagation + queuing

▼

Receiver gets packet

│

│ ECN-marked? → ACK immediately

│ AR set? → ACK immediately

│ Otherwise → accumulate until 16KB

▼

ACK sent (control priority via receiver NIC)

│

│ propagation (return path)

▼

Sender processes ACK → quadrant decision → cwnd update

9. NSCC vs TCP Cubic vs DCQCN

A clean way to compare congestion control algorithms is the triple: Knob (what you control) + Signal (what you observe) + Assumptions (what world you believe in).

Side-by-Side

| Property | NSCC | TCP Cubic | DCQCN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Delay + ECN | Loss (+ optional ECN) | ECN via CNP |

| Actuator | Congestion window | Congestion window | Sending rate |

| Increase shape | Proportional to headroom | Cubic function of time | Timer-driven steps |

| Decrease shape | Proportional to severity | Typically β=0.7 (config-dependent) | α-proportional cut |

| Pacing | NIC-limited (htsim) | Typically ACK-clocked; SW pacing optional | Hardware rate limiter |

| Multi-path | Native (per-packet spraying) | Single-path | Single-path |

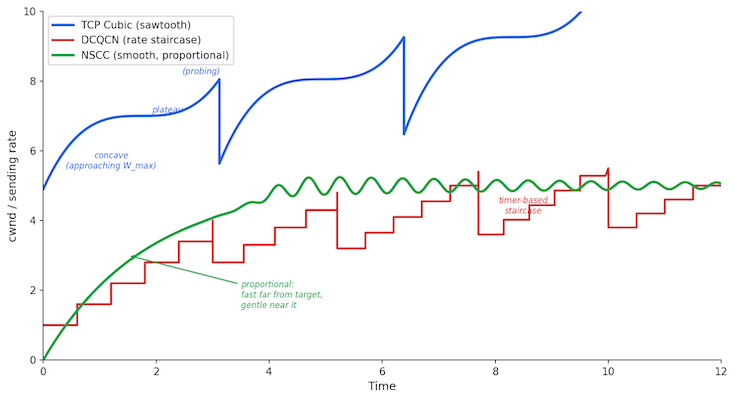

TCP Cubic reduces its rate sharply when it detects loss, then increases the rate over time following a cubic pattern. DCQCN, on the other hand, changes its rate in steps at set time intervals. NSCC adjusts its rate smoothly, changing both the direction and size of adjustments based on the current network conditions. This smooth adjustment is important because it reduces queuing changes, lowers packet loss, and makes latency more predictable when the network is stable. Here is an example of how the congestion window or sending rate might change over time for each.

10. Conclusion

In this post, I’m trying to make sense of NSCC by going through research papers and the htsim code. I’m not sure if I have understood everything correctly, so I’d really appreciate any corrections. The UE spec is the main reference, and the simulator is just one possible implementation. My goal is to give you a starting point with enough background and explanations, and to be clear about what I do and don’t fully understand.

References

- UE Ultra Ethernet’s Design Principles and Architectural Innovations, arXiv:2508.08906

- FASTFLOW: Flexible Adaptive Congestion Control for High-Performance Datacenters (earlier drafts titled SMaRTT-REPS, arXiv:2404.01630v3

- DCTCP Data Center TCP, RFC 8257

- TCP CUBIC for Fast and Long-Distance Networks, RFC 9438

- Congestion Control for Large-Scale RDMA Deployments

- DCQCN+: Taming Large-Scale Incast Congestion in RDMA over CEE Networks

- TIMELY: RTT-based Congestion Control for the Datacenter

- Swift: Delay is Simple and Effective for Congestion Control in the Datacenter