Lagrangian Methods in Constrained Optimization

An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field. - Niles Bohr

In this post, we will examine Lagrange multipliers. We will define them, develop an intuitive grasp of their core principles, and explore how they are applied to optimization problems.

Foundational Concepts

Lagrange multipliers are a mathematical tool employed in constrained optimization of differentiable functions. In the basic, unconstrained scenario, we have a differentiable function $f$ that we aim to maximize (or minimize). We achieve this by locating the extreme points of $f$, where the gradient $\nabla f$ is zero, or equivalently, each partial derivative is zero. Ideally, these identified points will be (local) maxima, but they could also be minima or saddle points. We can distinguish between these cases through various means, including examining the second derivatives or simply inspecting the function values.

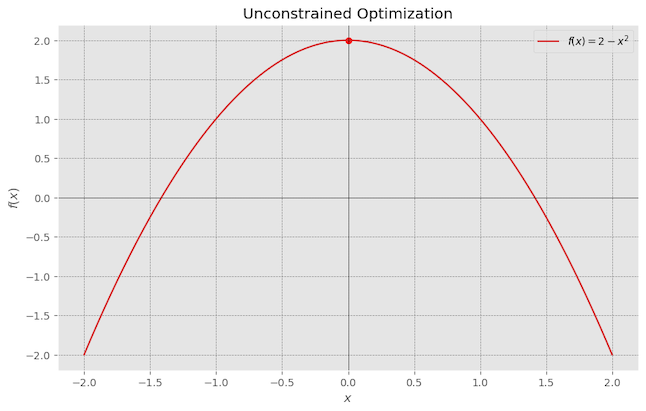

let’s look at this simple example where we have $f(x) = 2-x^2$, and we know this function has a maxima at $x=0$, $f(x) = 2$. we can find the maxima by taking the derivative and second derivate of the function to find the maxima of the function.

- Gradient: $\nabla f =0$.

- Extreme Point: Solve $\nabla f =0$, which gives x = 0.

In constrained optimization, we have the same function $f$ to maximize as before. However, we also have restrictions on the points that we’re interested in. The points satisfying our constraints are referred to as the feasible region. A simple constraint on the feasible region is adding boundaries, such as insisting that each $x_{i}$ be positive. Boundaries complicate matters because extreme points on the boundaries generally won’t meet the zero-derivative criterion and must be searched for using other methods.

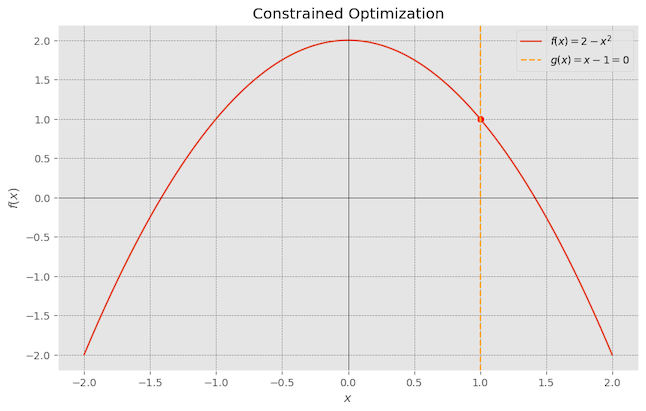

Building on the previous example, if we add a constraint that, the maximum value of the function $f(x) = 2-x^2$ needs to also meet the constraint that $x=1$. Clearly, the previous maxima value at x=0, where the $f(x)=2$, doesn’t meet that constraint. The maxima for this function $f(x)$, which meets the constraint $g(x)$, is $1$. You can see how finding the function local maxima (minima) using derivative won’t work here because the slope is not zero at this point.

We can use a simple substitution method by substituting the constraint into the main objective function.

- Objective Function: $f(x) = 2 - x^2$.

- Contraint: $g(x) = x-1$.

since the constraint is $x=1$, we can substitute this directly into the function:

\[\hspace{5cm} f(1) = 2 - 1^2 = 1\]

Now let’s look at a slightly more complex example:

- Objective function: $f(x,y) = 2 - x^2-2y^2$

- Constraint: $g(x,y) = x^2-y^2-1=0$

To solve this we can express $y$ in terms of $x$ from the constraint $x^2-y^2=1$:

\[\hspace{5cm} y = \pm \sqrt{1-x^2}\]Then substitute $y$ back into $f$:

\[\hspace{5cm} f(x,\sqrt{1-x^2}) = 2 - x^2-2(1-x^2) = 2-x^2-2+2x^2 = x^2\] \[\hspace{5cm} f(x,-\sqrt{1-x^2}) = 2 - x^2-2(1-x^2) = 2-x^2-2+2x^2 = x^2\]The maximum value occurs at $x=\pm1$ and $y=0$. We can see in the below plot that the surface of the function $f(x)$ and the constraint $g(x)$ shown by the red circle on the surface which bounds the maximum value the function $f(x)$ can have. Feel free to play with the figure and observe the function from various points of view to get some intuitive understanding on why the max value occurs at $x=\pm1$ and $y=0$.