Packet Classification for High Speed Packet Processing

“We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge.” - John Naisbitt

Introduction

I have always found packet classification to be quite dull; however, it is one of the most challenging problems—so I’m finally taking the time to organize my thoughts.

At its heart, packet classification involves figuring out how routers and network devices should handle each incoming packet, guided by predefined rules or policies. Each rule describes conditions based on multiple header fields, like source and destination IP addresses, port numbers, and protocols. When packets arrive, devices must quickly and accurately match them against these rules to decide whether to forward, drop, prioritize, or otherwise handle them.

A packet can be viewed as a tuple of header fields $(H_1, H_2, \dots, H_d)$, where each field represents a specific packet attribute, such as the source IP, destination IP, or port numbers. The classifier consists of a set of $N$ rules, where each rule $R_i$ defines matching criteria across these header fields. The matching conditions in a rule can include:

- Exact match: The header field must exactly match a specified value.

- Prefix match: The header field must match a common prefix defined in the rule (commonly used with IP addresses).

- Range match: The header field must fall within a specified numerical range.

| Rule | SRC | DST | Protocol | SRC Port | DST Port | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * | 192.1.104/24 | * | * | 80 | Discard |

| 2 | 2.0.32/20 | * | TCP | * | * | Forward to R3 |

| 3 | * | 192.1.251.1/32 | TCP | * | 80 | Forward to R2 |

| 4 | * | 192.1.23/24 | UDP | 17-99 | * | Allow $\leq$ 5 Mbps |

| 5 | * | 2.0.32/24 | TCP | * | 21-88 | Permit |

When a packet arrives, it may match conditions specified in multiple rules. To resolve these conflicts, rules are typically prioritized, and the packet is processed according to the highest-priority matching rule.

Why Packet Classification is Challenging

Efficient packet classification is critical yet challenging due to several competing design considerations:

- Speed: Classifications must occur at wire speed. For example, on a 400 Gbps link, packets of around 500 bytes arrive approximately every 10 nanoseconds.

- Memory Efficiency: High-speed packet classification demands compact and efficient data structures that fit into fast, limited-size memory (like SRAM). While hardware like TCAM can provide constant-time lookups, it consumes significant power and chip space.

- Scalability: As the number of rules increases—from hundreds to tens of thousands—the classification algorithm must scale without a proportional increase in search time.

A naive approach—performing a linear search through every rule—quickly becomes impractical as rule sets expand. For instance, checking 10 rules at 400 Gbps (assuming 512-byte packets) would consume around 100 ns, and 100 rules would take around 1,000 ns. Consequently, researchers and engineers have developed sophisticated methods such as hierarchical and grid-based tries, bit vector schemes, cross-product techniques, tuple-space approaches, and decision-tree methods. Each offers unique trade-offs regarding speed, memory usage, and ease of updates.

TWO-DIMENSIONAL SOLUTIONS

Packet classification becomes notably more complex when considering multiple fields simultaneously. However, analyzing the simplest scenario—two-dimensional classification—can provide valuable insights into managing additional dimensions efficiently.

Two-dimensional rules naturally extend one-dimensional lookup methods. Techniques originally designed for single-field classification, such as binary tries, can be adapted to effectively handle an additional header field, offering a straightforward approach to understanding and building more complex multi-field classifiers.

HIERARCHICAL TRIES: TRADING TIME FOR SPACE

A hierarchical trie extends the concept of a binary trie—commonly used for one-dimensional longest prefix matching—to handle additional header fields. The hierarchical trie approach works as follows:

The hierarchical trie approach works as follows:

- First Field Trie (F1 Trie):

- Construct a binary trie containing all unique prefixes from the first field (F1) of the rules.

- Each node represents a binary decision (0 or 1), and leaves correspond to specific prefixes.

- Second Field Tries (F2 Tries):

- For each distinct prefix node in the F1 trie, build a separate binary trie for the corresponding prefixes of the second field (F2).

- Each F2 trie is constructed using prefixes from rules that share the same prefix in the first field.

- Linking Tries:

- Nodes in the F1 trie contain pointers (“next-trie pointers”) that link directly to the root of their corresponding F2 trie.

The result is a collection of $F_2$ tries hanging off the $F_1$ trie, forming a “hierarchy.”

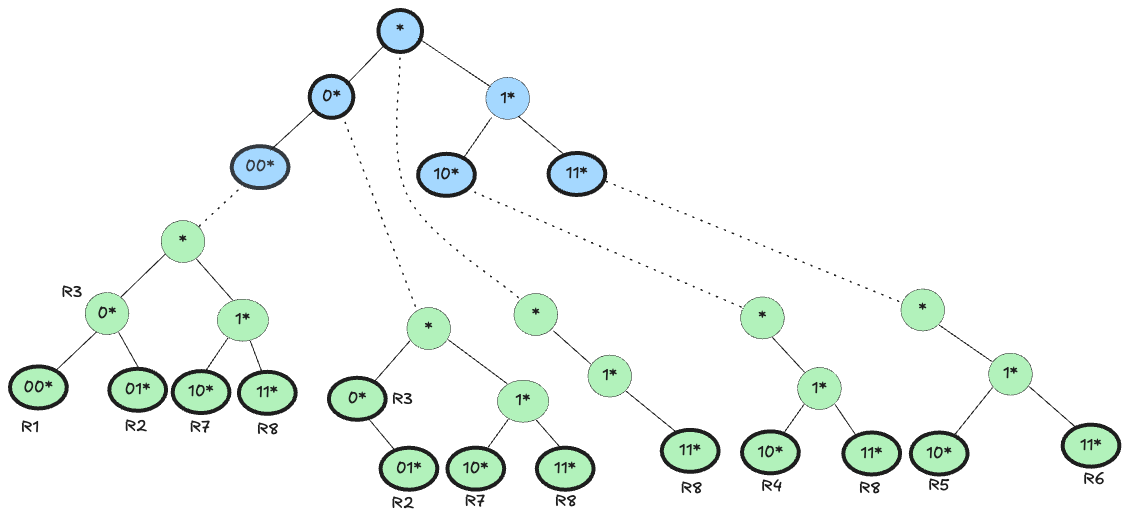

An example:

| Rule | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | 00* | 00* |

| R2 | 0* | 01* |

| R3 | 0* | 0* |

| R4 | 10* | 10* |

| R5 | 11* | 10* |

| R6 | 11* | 11* |

| R7 | 0* | 10* |

| R8 | * | 11* |

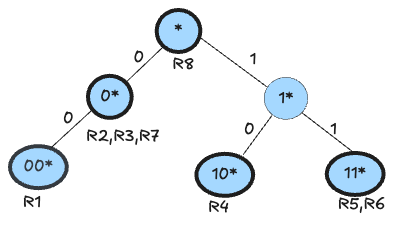

F1 Trie:

F2 Trie:

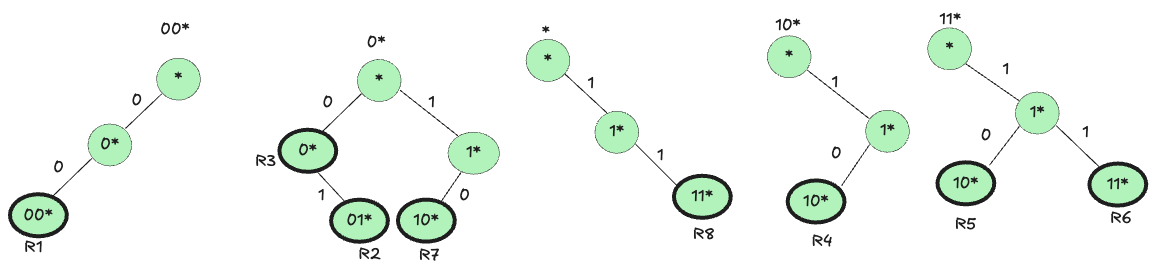

Linked F1 and F2 Trie:

Search Process: To classify a packet with header fields $F_1$ and $F_2$:

- Traverse the F1 Trie: Start from the root of the F1 trie, following the bits of the packet’s first header field to find the longest matching prefix.

- Traverse the Corresponding F2 Trie:** Using the next-trie pointer from the identified node in the F1 trie, move to the associated F2 trie. Search the F2 trie using the bits of the packet’s second header field.

- Backtracking: After finding an initial match, backtrack to ancestor nodes in the F1 trie, checking their corresponding F2 tries for potential higher-priority matches. Continue until you have verified all relevant tries, ultimately selecting the highest-priority match.

Let’s classify a packet whose fields are $F_1 = 000$ and $F_2 = 000$.

- Match in $F_1$ Trie:

- We traverse the $F_1$ trie from the root, following bits of $\hat{F}_1 = 000$.

- The longest match in the $F_1$ trie is “00*”, so we land on the node representing “00*”.

- Look Up in $F_2$ Trie for “00*”:

- From the node “00*” in the $F_1$ trie, we follow the next‐trie pointer to its $F_2$ trie.

- In that $F_2$ trie, we search for $F_2 = 000$.

- Suppose we find a match for “00*” in $F_2$. That corresponds to rule $R_1$. We record $R_1$ as our best match so far.

- Backtrack to Check Ancestors:

- Because a shorter prefix in $F_1$ (like “0*”) might combine with a longer or earlier‐priority prefix in $F_2$, we backtrack one level up the $F_1$ trie to “0*”.

- We then follow “0*“’s next‐trie pointer to its $F_2$ trie and look for $F_2 = 000$ there.

- In that trie, we may find a match for “0*” (rule R3), but we compare R3 to our current best (R1). If R1 has higher priority (or occurs earlier in the classifier), we keep R1.

- Continue Until Root

- We backtrack again to the root node of the $F_1$ trie (which corresponds to prefix “*”), follow its pointer to the “*” $F_2$ trie, and search $F_2 = 000$.

- If no matching rule there is higher priority, we remain with R1.

- Having returned to the root and checked all possible ancestors, we conclude that the best match is R1.

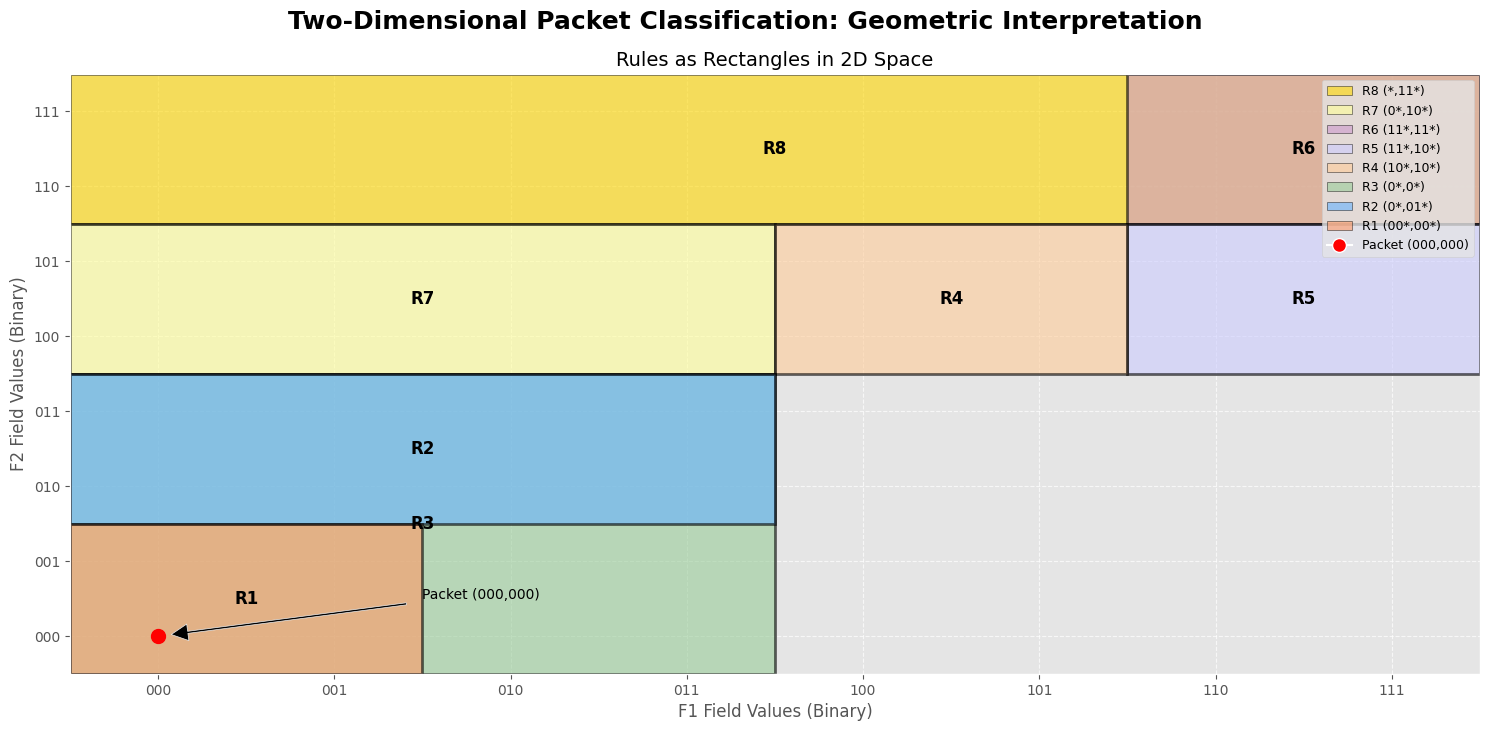

Geometric Representation

A geometric perspective offers valuable insights into packet classification by visualizing the problem as one of locating points within a multidimensional space. Each packet header can be represented as a point within this space, while classification rules correspond to defined regions or boundaries.

This geometric interpretation provides two significant advantages:

Problem Mapping: The packet classification task naturally translates into a well-studied computational geometry problem: point location in multidimensional spaces. Numerous algorithms have been explored for this specific challenge, providing established techniques and theoretical foundations.

Performance Bounds: We can leverage known theoretical bounds by mapping packet classification to geometric problems. Generally, for dimensionality greater than three $(d \gt 3)$, optimal algorithms have been shown to achieve either an $O(log^{d-1}N)$ search time complexity with $O(N)$ space or an $O(log N)$ search complexity with $O(N^d)$ space.

However, despite their theoretical elegance, these bounds highlight practical limitations, particularly for high-speed routers. Such algorithms typically demand excessive computational resources or memory space, making them less viable for real-world applications.

Time and Space Complexity

Two key factors are essential when analyzing the complexity of packet classification: time complexity (the speed of classification) and space complexity (the memory required by data structures).

Let $N$ represent the total number of rules in the classifier. For instance, if our classifier contains 100 rules, $N$ equals 100. Let $W$ represent the maximum number of bits used in any prefix of the fields, such as the 32 bits for IPv4 addresses. In general, $W$ indicates the maximum depth of the trie, which directly corresponds to the number of binary decisions required.

In the worst-case scenario, classification involves traversing multiple tries:

- We may need to examine up to $W$ distinct second-field ($F_{2}$) tries, corresponding to each bit of the longest prefix matched in the first field ($F_{1}$).

- Searching each of these $F_{2}$ tries individually requires time proportional to O(W).

Thus, the total worst-case time complexity for classification is $O(W^2)$, reflecting the potential to traverse up to $W$ tries, each taking $O(W)$ steps.

For Space complexity, which concerns the memory used by these trie-based data structures:

- Each prefix stored requires memory proportional to $W$.

- Since an $F_{2}$ trie is constructed for each distinct prefix of the $F_{1}$ field, the total space required is $O(N \times W)$.

Consequently, the memory requirement scales linearly with the number of rules $N$ and the depth $W$, highlighting a direct relationship between rule count, trie complexity, and space utilization.

Set Pruning Tries: Trading Space for Time

Set pruning tries enhance traditional hierarchical tries by significantly reducing classification time through additional memory use. This approach strategically replicates rules across multiple tries, eliminating the need for backtracking during packet classification.

How Set Pruning Works:

- Construct the First Field Trie ($F_{1}$ Trie):

- Similar to hierarchical tries, begin by building a binary trie for all unique prefixes of the first field ($F_{1}$).

- Build Second Field Tries ($F_{2}$ Tries) with Rule Replication:

- For each node in the $F_{1}$ trie, construct an associated $F_{2}$ trie.

- Unlike hierarchical tries, set pruning explicitly replicates rules from ancestor nodes in these $F_{2}$ tries. Consequently, each $F_{2}$ trie includes all relevant rules—those matching exactly the $F_{1}$ prefix at the node and those matching any ancestor prefixes.

The classification process becomes simpler and faster:

- Step 1 ($F_{1}$ Match): Identify the longest matching prefix in the $F_{1}$ trie.

- Step 2 ($F_{2}$ Lookup without Backtracking): Immediately proceed to the corresponding $F_{2}$ trie and perform a lookup without backtracking to ancestor nodes. All applicable rules have already been replicated within this trie.

- Step 3 (Determine Best Match): Quickly identify the highest-priority rule directly from this single lookup.

For example: With set pruning, the $F_2$ trie for the node “00*” is built to include not only R1 (which exactly has $F_1$ = “00*”) but also all rules whose $F_1$ prefix is an ancestor of “00*”. Since “00*” is more specific than “0*”, the rules R2, R3, and R7 (all with $F_1$ = “0*”) must be included. Additionally, the wildcard rule R8 (with $F_1$ = “*”) also applies. Thus, the $F_2$ trie for “00*” will contain the $F_2$ prefixes for R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8.

Step 1: $F_1$ Match Suppose a packet arrives with an $F_1$ value that matches “00*”. In the $F_1$ trie, you quickly identify “00*” as the longest matching prefix.

Step 2: $F_2$ Lookup Without Backtracking Rather than backtracking to check parent nodes (like “0*” or “_”), you follow the pointer to the $F_2$ trie associated with “00*”. Since this $F_2$ trie already contains the $F_2$ prefixes from R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8, you perform a single search for the packet’s $F_2$ field.

Step 3: Identify the Best Match The search in the $F_2$ trie finds the longest matching $F_2$ prefix among the replicated rules. This match is the final decision for the packet classification without needing any further backtracking.

Trade-offs:

Speed: Set pruning tries to significantly speed up the classification process by avoiding repeated backtracking through ancestor nodes, achieving an overall $O(W)$ lookup time.

Memory Cost: The primary trade-off is increased memory usage. Replicating rules within multiple F₂ tries can lead to substantial memory overhead, potentially reaching $O(N^2)$ in the worst-case scenario. However, practical optimizations, such as sharing common trie structures, can often mitigate this effect.

In essence, set pruning tries to effectively trade additional memory resources for considerable improvements in classification speed, making them particularly suitable for environments prioritizing performance over memory efficiency.

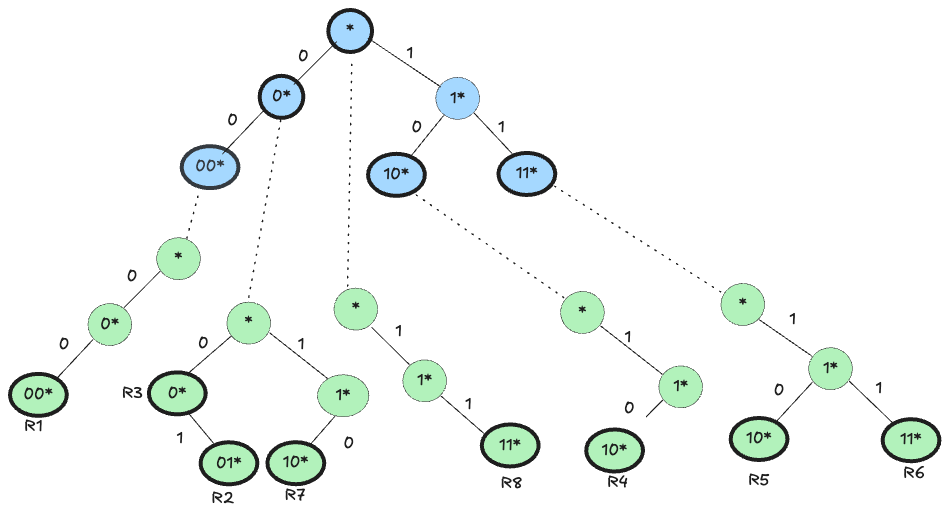

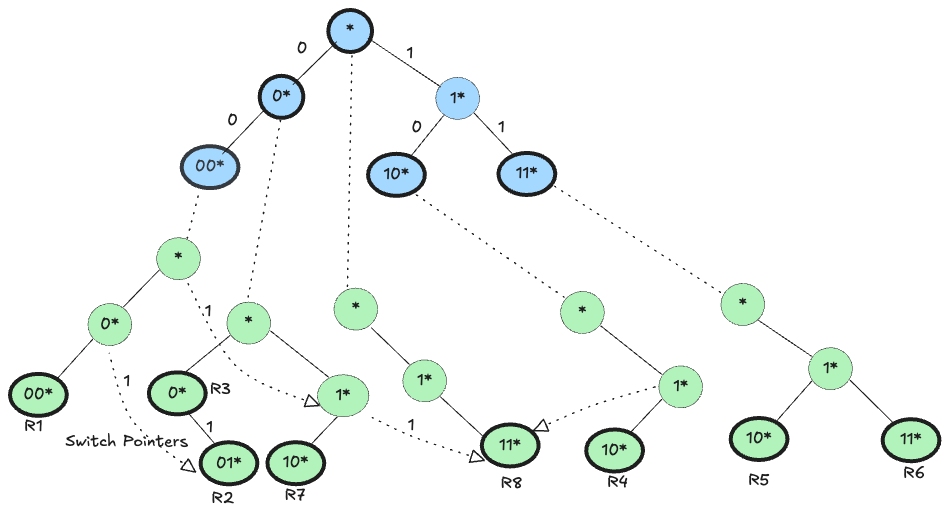

GRID-OF-TRIES: BEST OF BOTH WORLDS

The grid-of-tries data structure merges the advantages of hierarchical and set pruning tries. It aims to achieve fast lookup times comparable to set pruning tries while minimizing memory usage, similar to hierarchical tries.

Key Features:

-

Single Rule Storage: Unlike set pruning tries, where rules are duplicated across multiple second-field ($F_2$) tries, grid-of-tries stores each rule only once. This keeps memory usage efficient, typically on the order of, where is the number of rules, and is the maximum prefix length.

-

Precomputed Switch Pointers: Traditionally, hierarchical tries require backtracking in the first-field ($F_1$) trie upon failure in an associated $F_2$ trie. Grid-of-tries avoids this overhead by using precomputed switch pointers, which allow immediate transitions from failure points in one $F_2$ trie to corresponding positions in less specific (ancestor) $F_2$ tries. Thus, searches can continue efficiently without restarting from scratch.

-

Maintaining Best-Match Information: Each node in the $F_2$ trie retains additional information—referred to as the “best-match rule encountered so far.” This stored information ensures the best available match is preserved even when the search path skips certain nodes due to switch pointer usage.

For Example: Consider classifying a packet with header fields and:

-

$F_1$ Trie Traversal: Begin traversing the $F_1$ trie using bits from the packet’s first header field. Suppose the longest matching prefix found is “00*”. Follow the pointer from this node to its corresponding $F_2$ trie.

-

$F_2$ Trie Search: Traverse the $F_2$ trie for “00*” using bits of the packet’s second header field. If a mismatch occurs (for example, at the first bit), rather than restarting the search, utilize the precomputed switch pointer.

-

Switch Pointer Usage: The switch pointer quickly moves the search to the corresponding node in the $F_2$ trie of a less specific $F_1$ prefix (such as “0*”). The search then resumes seamlessly.

-

Search Continuation and Decision: This process of utilizing switch pointers repeats until the most specific applicable rule is found, using stored best-match information at each node to determine the optimal final decision.

Consider classifying a packet with the header values of F1 = 000 and F2 = 110. The search for “000” in the F1 trie results in “00*” as the best match. Using its next-trie pointer, the search continues on the F2 trie for 110. However, it fails in the first bit 1. Hence, the switch pointer is used to jump to the node containing rules R2,R3 and R7. Similarly, when the search on the next bit fails again, we jump to the node containing rule R8 in the F2 trie associated with the F1 prefix $*$. Hence, the best matching rule for the packet is R8. As can be seen, the switch pointer eliminates the need for backtracking in a hierarchical trie without the storage of a set pruning trie. Essentially, it allows us to increase the length of the matching F2 prefix without having to restart the search from the root of the next ancestor F2 trie.

Ensuring Correctness: To address scenarios where direct matches might be overlooked due to jumps facilitated by switch pointers, each node includes an extra

variable—storedRule. This variable retains information about the best potential match encountered during the search. Thus, even when direct traversal misses

some paths, the algorithm consults storedRule to ensure it always identifies the optimal matching rule.

Efficiency Considerations:

- Time Efficiency: Grid-of-tries achieves lookup time, involving at most steps for the $F_1$ trie traversal and another steps for the $F_2$ trie traversal. By eliminating repetitive backtracking, the overall time performance remains highly efficient.

- Space Efficiency: Memory usage remains moderate at approximately, thanks to storing each rule precisely once, significantly conserving resources compared to set pruning techniques.

Practical Limitations of Trie-Based Schemes

Although trie-based schemes offer a theoretically elegant solution for packet classification, they often face significant challenges in real-world applications. The main practical limitations revolve around deterministic latency, memory constraints, and update complexity.

Deterministic Latency: Trie-based structures’ latencies heavily depend on the number of sequential memory accesses required for lookups. In a hierarchical trie, a lookup typically involves traversing from the root to a leaf node (depth-W), with potential backtracking to evaluate overlapping prefixes. Set pruning mitigates this by replicating subtrees, effectively reducing traversal steps to about seven. Similarly, grid-of-tries structures maintain the seven-step depth through pointer indirections rather than direct subtree duplication. However, even seven sequential memory accesses will be problematic where deterministic, minimal latency is critical.

Memory Constraints: Trie-based approaches typically suffer from substantial memory overhead precisely when hardware resources are most limited. Set pruning accelerates lookups by replicating destination-prefix subtrees under each longer source-prefix branch. This replication causes the memory requirement to grow significantly, typically proportional to the product of prefix counts. Although grid-of-tries replaces direct replication with pointer-based indirections to save space, these pointers introduce additional overhead. They require extra memory for storage and often disperse nodes across different memory pages, disrupting the efficient use of wide-word, burst-friendly SRAM structures common in modern ASIC designs.

Complexity of Updates: Updating trie-based structures in live network environments poses significant operational challenges. Each rule insertion or deletion can lead to extensive reconfigurations—hierarchical tries might trigger node splits, set pruning tries could necessitate subtree replication, and grid-of-tries might require extensive pointer updates. These complex update operations can result in transient performance degradations, manifesting as brief stalls in packet lookups (micro-bursts). Network designers often need to allocate additional shadow memory or computational resources to maintain seamless operation, increasing system complexity and cost.

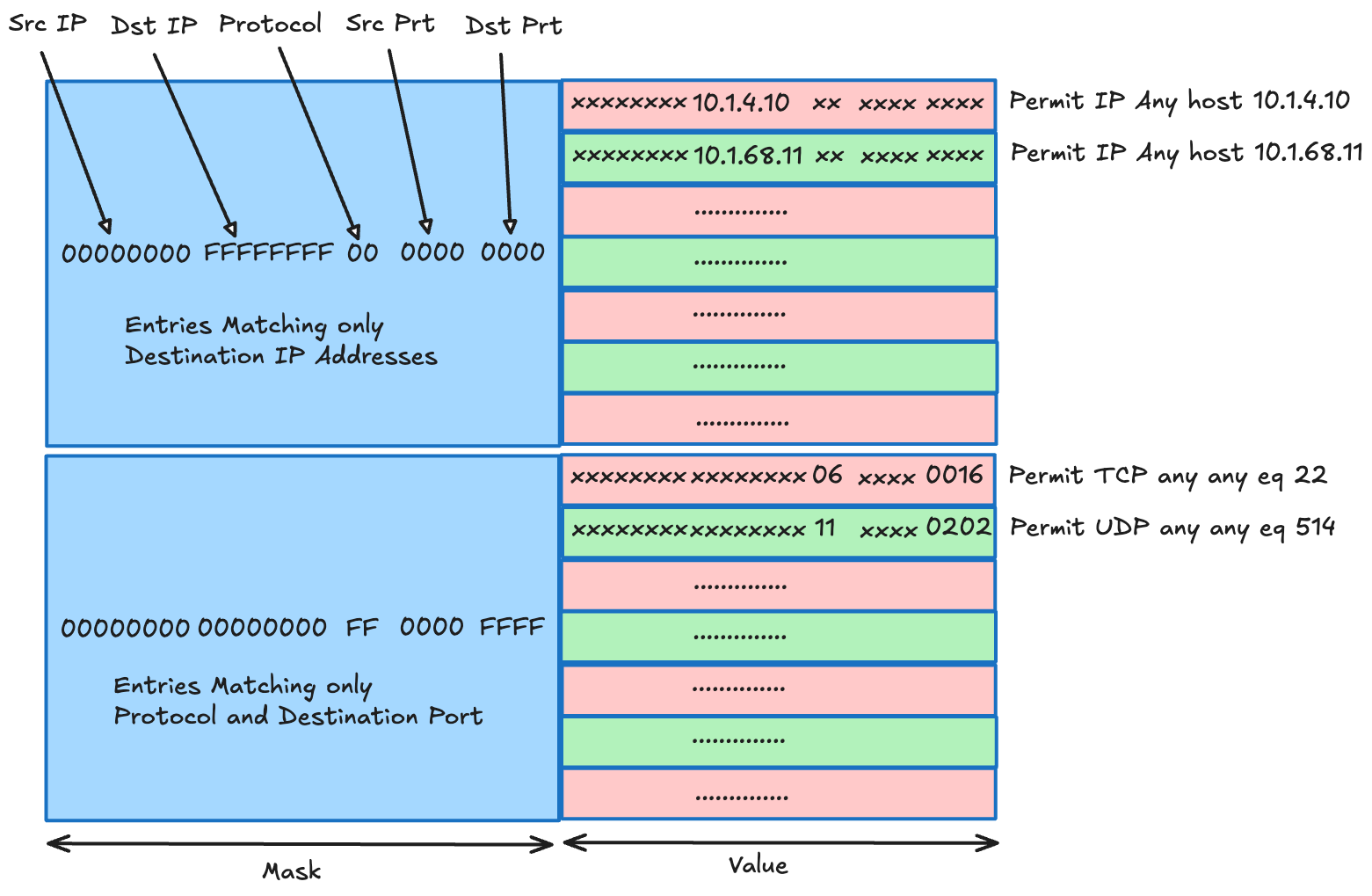

TCAM

TCAM is specialized hardware memory designed for high-speed packet classification and can perform ternary logic matches on packet headers. Unlike conventional memory types (such as SRAM or DRAM) that store only binary bits (0 or 1), TCAM can represent an additional “wildcard” state (*), enabling entries to match bit patterns flexibly.

In TCAM-based classification, relevant packet header fields—such as IP addresses, ports, protocols, and DSCP values—are concatenated into a single lookup key. This key is simultaneously compared against all stored TCAM entries in parallel. The first entry to match (the highest priority rule) determines the packet’s action, including permit, deny, or applying QoS treatments. One of TCAM’s critical advantages is its deterministic, constant-time lookup performance. Because all entries are evaluated concurrently, lookup latency remains consistently low regardless of the number of stored rules, making TCAM indispensable for maintaining line-rate forwarding in high-performance networks.

However, the benefits of TCAM come with significant trade-offs. Each TCAM bit requires substantially more transistors (typically between 10 and 16 transistors per bit) compared to SRAM (~6 transistors per bit) or DRAM (~1 transistor per bit). Consequently, TCAM consumes more power and silicon area, limiting its scalability and size in practical network devices.

Due to these constraints, TCAM is often reserved for complex packet classification tasks that are challenging or inefficient to implement algorithmically, such as multi-field Access Control Lists (ACLs). In modern switch ASIC architectures, TCAM is treated as a scarce resource and is usually provisioned separately from other memory tables to optimize usage and performance.

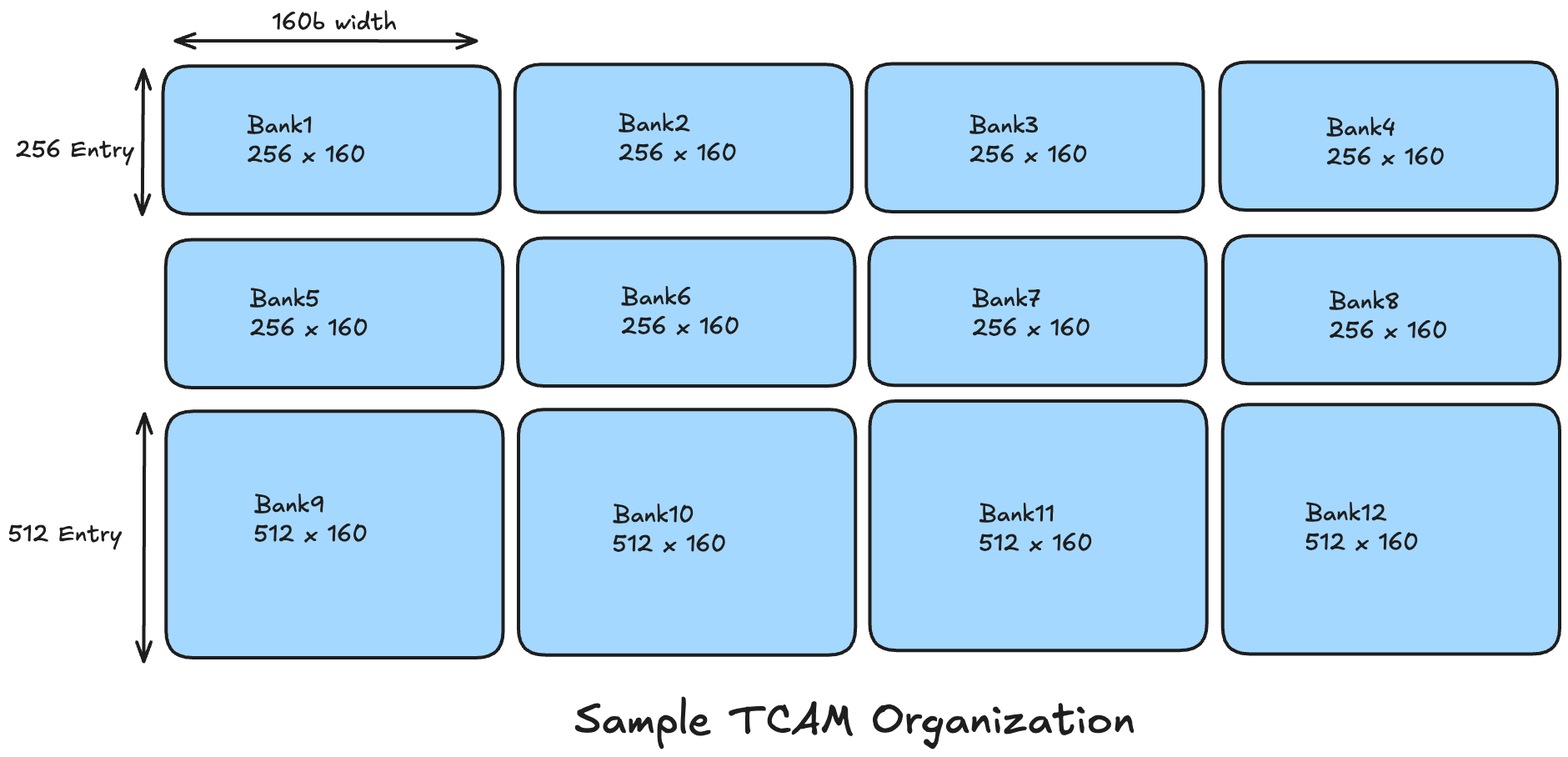

TCAM Memory Organization

Rather than one monolithic TCAM array, high-speed switch ASICs typically implement TCAM as multiple smaller banks or slices. Each slice is a self-contained chunk of TCAM (with a fixed number of entries) that can operate in parallel with others. For example, an ASIC can have an ingress ACL TCAM of 4K total entries, divided into 8x 256-entry and 4x512-entry slices. A slice can be a minimum allocation unit for a feature’s table; some features might be assigned one or multiple slices depending on size needs.

A lookup can be directed to a specific bank or broadcast to all banks in parallel. In a simple design, a packet’s key might be searched through all banks simultaneously, and the earliest matching entry (considering global priority) yields the result. The system often uses a pre-classification (such as hashing or prefix partitioning) to steer the lookup to a particular bank so only that bank is activated for the search. This steering avoids searching every bank, crucial for reducing power and preserving speed.

Many ASICs are internally split into several identical forwarding pipelines, each handling a subset of ports. Each pipeline may have an ingress and egress stage, each with its own TCAM slice. In effect, the total TCAM is physically distributed across slices per pipeline. For example, Cisco’s CloudScale ASIC has a dual-die design with four slices (pipelines) per die; the classification TCAM capacity is often quoted “per slice” (e.g., 5K ingress ACL entries per slice) with an ability to also have some shared entries across slices. The architecture ensures each slice can perform lookups independently for the ports it controls, and a slice interconnect meshes the ingress and egress slices so that any ingress slice can forward to any egress slice non-blocking

Multiple TCAM slices mean lookups can be parallelized, but each slice has a smaller share of the total TCAM. If one interface needs more ACL entries than a single slice supports, some platforms allow “borrowing” slices from an adjacent pool or chaining slices (at some latency cost). In pipeline-based designs, the number of slices can also dictate the maximum number of distinct lookup operations. Cisco’s Catalyst 9500X (Q200 ASIC), for instance, has a multi-slice lookup pipeline: it can perform six parallel exact-match or LPM lookups (one per slice) and 12 parallel TCAM lookups (two per slice, likely ingress and egress). This shows how slices partition memory and divide the lookup workload for throughput. Platforms usually have enough slices to handle full port rates without stalling.

Key Width and TCAM Entry Sizing

The width of packet classification keys used in TCAM depends significantly on the protocols (e.g., IPv4 or IPv6) and the matched header fields. Typically, these keys are formed by concatenating several packet header attributes—such as source and destination IP addresses, Layer 4 ports, protocol numbers, VLAN tags, and other relevant metadata—into a unified bit string for TCAM lookup operations.

A critical consideration in TCAM sizing arises from the length differences between IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. IPv6 addresses, at 128 bits each, are four times longer than IPv4 addresses, which are 32 bits each. Consequently, IPv6-based Access Control Lists (ACLs) and policy rules inherently demand wider classification keys, substantially impacting TCAM utilization.

To efficiently handle variable key widths, modern TCAM implementations support multiple entry widths:

-

Single-wide entries: These can accommodate typical IPv4 ACL rules or simpler matching criteria. Each single-wide entry stores the entire key within one TCAM slot.

-

Double-wide (or multi-width) entries: Used for IPv6 or combined match criteria that exceed the single entry width. In hardware, an IPv6 rule may consume two TCAM entries (effectively splitting the 128-bit address across two standard-width entries). This doubles the TCAM space used per the IPv6 rule, reducing the overall capacity for IPv6 ACLs by half compared to IPv4. For example, on Cisco Nexus 9000 switches (pre-CloudScale), IPv4 TCAM regions are single-wide, while IPv6, QoS, MAC, and other regions are double-wide and consume double the physical TCAM entries. In practice, a logical region of 256 IPv6 entries would consume 512 TCAM slots on those ASICs.

-

Triple-wide entries: In some architectures, certain matches (e.g., IPv6 with additional fields or longer keys) might require three TCAM slots per entry. Nokia’s FP routing ASICs are one example – on the Nokia 7220 IXR-D1, ingress IPv6 ACL entries operate in “triple-wide” mode, using 3 TCAM slices per rule (versus single slice per IPv4 rule). In that system, up to ~6144 IPv4 ACL entries are supported per stage (8 slices × 768 entries each), but only 768 IPv6 entries (since each IPv6 consumes three slices).

The need for double- or triple-wide entries means enabling IPv6 classification, which can dramatically reduce the usable TCAM space.

Some ASIC variations have eliminated the need to statically separate IPv4 and IPv6 regions and unify the ACL table so that a given region can hold IPv4 or IPv6 entries, using internal logic to count IPv6 entries as double. In other words, there is no fixed partition for double-wide vs single-wide. The hardware can mix them and uses 2 TCAM slots as needed for IPv6. This improves flexibility; earlier designs often had rigid region carving (e.g., a dedicated IPv6 TCAM region that, if unused, couldn’t be repurposed for IPv4).

Memory Partitioning and TCAM Carving Strategies

Because TCAM is limited, partitioning it among features is a key issue. Network OS vendors provide configurable profiles or “TCAM carving” to allocate slices or entries for various purposes: IPv4 ACLs, IPv6 ACLs, QoS classifiers, route lookups, etc. By default, many switches come with a balanced profile. If users need more ACL entries, they may have to shrink another region (say, reduce the L2 MAC address table or disable a feature that consumes TCAM) to free slices for reallocation.

TCAM Explosions

A TCAM row is a flat vector in which every packet header field is laid out side-by-side. Port ranges and the cartesian product effect are two common drivers for TCAM rows exploding.

Port-range expansion: TCAM can match exact values or wild cards but not arithmetic ranges (e.g., 1000–2000).The range is broken into power-of-two blocks, each becoming its own row.

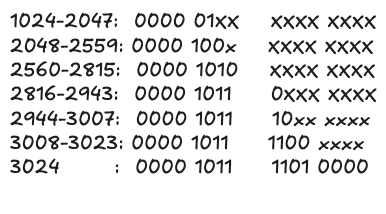

A greedy algorithm to identify how many TCAM rows are needed to cover a port range (ex: 1024-3024) is:

- Start at the lower bound (

cur = 1024), - Choose the largest power-of-two block that begins at cur and does not overshoot 3024.

- Emit one row for that block (prefix + mask).

- Advance

curand repeat.

For 1024-3024, it yields 7 rows:

Cartesian-product expansion: This issue occurs when rules combine multiple conditions (source IP addresses, destination IP addresses, ports, etc.). Each combination multiplies, creating numerous TCAM entries. A rule that lists $m$ source prefixes, $n$ destination prefixes, and $p$ port sub-ranges becomes $m \times n \times p$ rows.

Source IPs: {1.1.1.0/24, 10.1.1.0/24} {m=2}

Destination IPs: {2.2.2.0/24, 11.1.1.0/24} {n=2}

Destination Port: 1000-1031 → 4 sub-ranges (p = 4)

Total rows = 2 × 2 × 4 = 16. Add more prefixes, and the table balloons quickly.

To represent the range in one TCAM entry, all numbers within the range must match the entry’s masked bits exactly. All matched bits must be common to every number for a single entry to match the entire range.

Techniques for Efficient Range Encoding in TCAM

Range Pre-Encoding (DIRPE): One effective strategy for encoding ranges in TCAM is Database-Independent Range Pre-Encoding (DIRPE). This technique compresses ranges into fewer TCAM entries by pre-encoding them independently of any specific ACL database, making it universally applicable.

DIRPE works by dividing a 16-bit port number into smaller, manageable slices (e.g., 2 or 3 bits each). Each slice is encoded into a set of fence bits, represented using a thermometer-like code. For instance, a 2-bit slice (which can represent values 0 through 3) is encoded into three bits:

| Value | 2-bit slice | Encoding |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00 | 000 |

| 1 | 01 | 001 |

| 2 | 10 | 011 |

| 3 | 111 | 111 |

Example Encoding and Analysis: Let’s encode a practical example: the port range[1024, 3024]. First, split the 16-bit port field into

eight 2-bit chunks (C7 to C0). Each chunk uses fence encoding (3 bits per chunk), totaling 24 bits per TCAM entry. Here’s the encoding of

ports 1024 and 3024:

| Chunk | C7 | C6 | C5 | C4 | C3 | C2 | C1 | C0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1024 | 00 | 00 | 01 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| Fence | 000 | 000 | 001 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

| 3024 | 00 | 00 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| Fence | 000 | 000 | 011 | 111 | 111 | 001 | 000 | 000 |

Slices C7 & C6: These match exactly (00), so no new entry is emitted here. When slices match, we lock the slice value and descend.

Slice C5: First mismatch (low 01, high 10). We split:

- Lower fringe (01): Emit a wildcard entry covering all lower slices. This yields one TCAM row.

- Row 1(lower fringe): 000 000 001 xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx

- Upper (10): Fix this value and continue to the next slice.

Slice C4: (Under C5=2) Lower fringe (0xx) covers multiple values, yielding one more TCAM row. Upper value (11) moves to the next

slice. Row 2: (C5=2 , C4<3 ): 000 000 011 0xx xxx xxx xxx xxx

Slice C3: Similar splitting produces another TCAM row (0xx). The upper fringe (11) moves further down. Row 3: (C4=3, C3<3): 000 000 011 111 0xx xxx xxx xxx

Slice C2: Produces one row covering values below (000), yielding one additional entry. Row 4 (C3=3, C2<1): 000 000 011 111 111 000 xxx xxx

Slices C1 & C0: Identical (00), yielding the final exact-match TCAM row. Row 5 (C2=1, C1): 000 000 011 111 111 001 000 000

Final Set of TCAM Entries

Row 1: 000 000 001 xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx

Row 2: 000 000 011 0xx xxx xxx xxx xxx

Row 3: 000 000 011 111 0xx xxx xxx xxx

Row 4: 000 000 011 111 111 000 xxx xxx

Row 5: 000 000 011 111 111 001 000 000

Total bits used per entry: 3 bits/chunk * 8 chunks = 24 bits.

Range-TCAM and Dedicated Comparators: A straightforward way to keep port-range rules from mushrooming into dozens of TCAM rows is to push the range check into a dedicated comparator block beside the TCAM. The hardware programs two registers—LOWER and UPPER—and, on every lookup cycle, arithmetic comparators assert two one-bit signals: one goes high when the packet’s port is ≥ LOWER, the other when it is ≤ UPPER. Because the TCAM row only needs to verify that both bits are true, the entire range collapses to a single entry; the 16-bit port field never enters the TCAM key.

match (SRC_IP = 10.0.0.0/24) AND(DST_IP = 192.0.2.0/24) AND (LOU_low = 1) AND (LOU_high = 1) → permit

Some Classic Cisco platforms used to have Layer-4 Operation Units (LOUs), which provide 64 low-bound and 64 high-bound checks for source ports and the same for destinations so that we can encode up to 32 source-port and 32 destination-port ranges at once (each range consumes one $\geq$ and one $\leq$ LOU). As long as free LOUs exist, a rule that might otherwise splinter into a handful of prefixes occupies exactly one TCAM row. The trade-off is that the comparator pool is finite; once the LOUs are exhausted, the software must revert to prefix expansion. Still within its limit, this scheme delivers perfect compression without inflating the TCAM key width and without resorting to clever priority tricks at the cost of some extra silicon area and power for the comparators.

Overlap Encoding (Positive/Negative Encoding): An interesting encoding technique (found in Marvell’s patents) uses overlapping allow/deny entries to represent a range compactly. The idea is to encode a range $[A,B]$ by programming a broad allow rule that covers at least $[A,B]$ (and possibly more), then programming one or two block rules with higher priority to exclude the portions outside $[A,B]$. In other words, instead of explicitly enumerating everything inside the range, the hardware encodes the range implicitly by taking a superset and subtracting the out-of-range parts. Because TCAM entries can represent prefixes/wildcards, a single “superset” pattern can often cover a wide span around $[A,B]$, and the out-of-range portion on each side might also be coverable by one pattern each. By giving those exclusion patterns higher priority (treating them as negative matches or rejects), the effect is that only the desired $[A,B]$ range is allowed. The positive entries are associated with the rule’s permit action, and the negative entries map to a reject action (higher priority). It’s beneficial when the hardware can’t add custom comparators; instead, it’s done by cleverly programming TCAM entries and priorities.

Divide and Conquer Approaches

Packet classification is inherently a multi-dimensional problem: each packet has several header fields (such as source/destination addresses, ports, and protocols), and each rule in the classifier defines conditions over these fields. Directly handling all dimensions simultaneously can be highly complex—both in terms of computation and memory—because the rules form hyperrectangles in a high-dimensional space, and the task is to locate the “topmost” (highest priority) rule that covers a given packet, represented as a point in this space.

The divide and conquer approach offers an elegant solution by breaking the problem into smaller, more manageable subproblems. The key idea is to decompose the multi-dimensional packet classification problem into independent searches on individual fields (or groups of fields), then combine these partial results to determine the final best matching rule. This strategy leverages the fact that many efficient algorithms already exist for one-dimensional or two-dimensional searches (like longest prefix matching), which can be applied independently to each field. Some key concepts are:

Decomposition: Instead of tackling the entire multi-field Search at once, the packet header is divided into its individual fields. For each field, a separate data structure (often based on efficient one-dimensional lookup techniques) is built to determine which rules match that particular field quickly.

Independent Search: Each field is processed independently. For example, one can perform the longest prefix match on the source address and separately on the destination address, port numbers, etc. These searches produce intermediate results—often in the form of bit vectors or equivalence class identifiers—that succinctly represent the rules matching each field.

Result Combination: The major challenge lies in merging these independent results to obtain the overall best matching rule. Several strategies have been proposed for this, such as:

- Lucent Bit Vector Scheme: Uses bit-level parallelism by associating a bitmap with each field’s match. The final rule is determined by intersecting these bitmaps.

- Aggregated Bit Vector (ABV): This method summarizes segments of the bit vectors to reduce memory accesses, though it may incur some false positives.

- Cross-Producting: Precomputes a table that maps every combination of partial matches (or equivalence classes) to the best overall rule. While conceptually straightforward, the size of this table can grow exponentially with the number of fields.

- Recursive Flow Classification (RFC): Merges intermediate results in stages, thereby gradually reducing the search space while still exploiting parallelism.

Challenges in Divide and Conquer:

- Combining Partial Results: Even if each field is processed quickly, merging the results without losing the correct rule (especially when multiple rules partially match different fields) is nontrivial. The integration must be both correct and efficient.

- Memory Access Overhead: Techniques such as bit vector intersection or table lookups may require multiple memory accesses. Although each independent Search is fast, the aggregation step must be optimized to keep overall latency low.

- Scalability and Worst-Case Behavior: In theory, the worst-case complexity for some of these methods can be very high (for example, cross-products may require space exponential in the number of fields). Fortunately, real-life classifiers usually exhibit structures (such as redundancy and limited distinct prefix lengths) that lower the effective complexity.

- Dynamic Updates: Many divide-and-conquer schemes rely on extensive pre-computation, which can make them less adaptable to environments where the rule set is frequently updated.

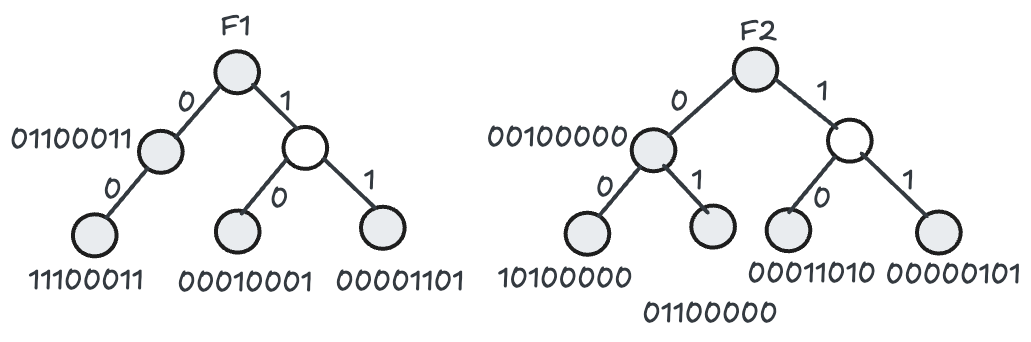

Lucent Bit Vector

Suppose we have a set of rules, each rule specifying constraints in $d$ header fields (for instance, two fields $F_1$ and $F_2$). The Lucent method begins by gathering the unique prefixes in each field across the rules. For field $F_1$, every unique prefix from the rules goes into a trie structure; the same happens for $F_2$. Each prefix in those tries is associated with a “bit vector,” whose length matches the total number of rules $N$. If the prefix in the field $F_1$ (or $F_2$) belongs to rule $R_j$, then the $j_{th}$ bit in its bit vector is set to 1; if it does not, the bit is 0.

When a packet arrives, the classifier extracts its relevant header fields $H_1, \ldots, H_d$. For each field, a longest‐prefix match is done in that field’s trie. This yields a bit vector for each field: for example, a packet matching prefix $00\ast$ in $F_1$ might produce the bit vector $11100011$, while the prefix $01\ast$ in $F_2$ might produce $01100000$. Once these bit vectors are found, they are intersected via a bitwise AND. The intuition is that only those rule positions set to 1 in all of the relevant fields’ bit vectors truly match across all fields. Hence, the intersection produces a single-bit vector indicating which rules in the global rule set actually match. If multiple bits remain set, the earliest matching bit (or the highest‐priority rule) is typically taken as the best match.

For example, imagine two fields $F_1 = 001$ and $F_2 = 010$. You first do a longest‐prefix match in the $F_1$ trie, which might return the bit vector $11100011$. Then, you do a longest‐prefix match in the $F_2$ trie, perhaps giving $01100000$. Performing a bitwise AND of $11100011$ and $01100000$ yields $01100000$. Interpreted as rule indices, that result might indicate that rule $R_2$ (the second-bit position) is the first match. Hence, rule $R_2$ is selected.

| Rule | $F_1$ | $F_2$ | $F_1$ Unique | $F_2$ Unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $R_{1}$ | 00* | 00* | 0* | 0* |

| $R_{2}$ | 0* | 01* | 00* | 00* |

| $R_{3}$ | 0* | 0* | 10* | 01* |

| $R_{4}$ | 10* | 10* | 11* | 10* |

| $R_{5}$ | 11* | 10* | * | 11* |

| $R_{6}$ | 11* | 11* | ||

| $R_{7}$ | 0* | 10* | ||

| $R_{8}$ | * | 11* |

This scheme improves performance because bitwise operations are extremely fast and can be further accelerated in hardware. The memory requirement is linear primarily in the number of rules multiplied by the width of the bit vectors, though in practice, there can be a high constant factor if many prefixes are used. Still, the benefit is that once you find the bit vectors for each field, a single AND operation pinpoints the candidate rules, making lookups and classification efficient compared to naive linear scans.

From a time‐complexity standpoint, each field lookup is typically proportional to the depth of its trie. If you assume the trie depth is at most $N$ (worst case) or, more practically, some function of the prefix lengths, this could be viewed as $O(d \cdot \log N)$ for the tries themselves in many real‐world scenarios (each lookup is a longest‐prefix search). However, once you retrieve the bit vectors, the bitwise AND takes $O(N / w)$ operations (where w might be the word size); in purely theoretical terms, storing and intersecting bit vectors that are each of length N suggests a worst‐case time of $O(N)$ for each classification (since you could do the AND bit by bit). Thus, if each field is processed in parallel or near‐parallel with specialized memory operations, the overall cost per packet becomes effectively linear in $N$, albeit with possible hardware speedups.

On the memory side, building a bit vector of length $N$ for every prefix can yield a high overhead. If a field contains up to $M_i$ distinct prefixes, that field’s trie must store up to $M_i$ bit vectors, each with $N$ bits, totaling $O(M_i \cdot N)$ bits. Summing over $d$ fields, if each field had roughly $M$ unique prefixes, the total memory requirement becomes $O(d \cdot M \cdot N)$. In a worst‐case scenario where many rules yield unique prefixes, $M$ could be in the same order as $N$, leading to $O(d \cdot N^2)$ bits. Because of this, the Lucent approach can demand substantial memory. However, the benefit is that once you have stored these bit vectors in memory (for instance, word size $w \approx 32$ or 1000 bits in specialized hardware), the intersection operations can be extremely fast. This trade‐off—more memory for faster lookups—makes the Lucent bit vector scheme viable for high‐speed classification hardware but also highlights the importance of carefully engineering the bit vector storage to avoid wasting memory on unused bits.

In practice, a critical factor for the Lucent bit vector scheme is how many bits you can fetch (and process) in one memory access. SRAM can support wide buses—128 bits, 256 bits, sometimes even 512 bits per read—reducing the number of accesses you need to retrieve (and combine) a large bit vector. High Bandwidth Memory (HBM), often stacked close to a processor core, uses multiple channels and wide interfaces internally, allowing the equivalent of large “word sizes” per time unit. As a result, you can stream blocks of hundreds or even a thousand bits at a time.

By storing the bit vectors in such wide memories, the Lucent scheme cuts down on the “N-bit intersection” overhead: rather than doing N single‐bit operations, you can do them $w$ bits at a time (where w might be a few hundred bits or more). For instance, if each memory fetch or write can transfer 512 bits, you reduce the total reads for each bit vector intersection by a factor of 512 relative to a simple 1‐bit‐wide access. In HBM specifically, the memory’s internal structure can be effectively leveraged to fetch large chunks in parallel, so you conceptually treat it like a large‐w memory (though some of the width is really spread across multiple internal channels).

Because each “chunk” of w bits can be bitwise‐ANDed in one or a few hardware cycles, the total cost for processing an N‐bit vector intersection scales roughly as O(N / w). If, for example, your ruleset N is 8,192 and your word size w is 512, then you only need 16 reads (8,192 / 512) to retrieve and process each bit vector. That still yields an O(N) bound in theory, but practically speaking, wide memory interfaces and parallelized bitwise operations can make the per‐packet classification extremely fast.

AGGREGATED BIT VECTOR (ABV)

The Aggregated Bit Vector (ABV) approach refines the Lucent scheme to cut down on expensive memory accesses by taking advantage of two typical observations in real‐world classifiers: (1) the bit vectors are often sparse (few bits are set to 1), and (2) each packet typically matches only a small number of rules. Instead of always retrieving and intersecting full N‐bit vectors, ABV constructs a smaller “aggregate” vector that summarizes chunks (or “blocks”) of the original bit vector. Specifically, each N‐bit vector is subdivided into k blocks of size A (so $N = k \times A$). The scheme then creates a single “aggregate” bit for each block: if any bit in that block is 1, its aggregate bit is 1; otherwise, it is 0. Thus, an original N‐bit vector is condensed into just $k = \lceil N / A \rceil$ aggregate bits.

When a new packet arrives, the classifier first does a longest‐prefix match in each field (as before) and retrieves the corresponding aggregate bit vector. These aggregate bit vectors are intersected (bitwise AND) to determine which blocks might contain common set bits across all fields. We only retrieve the corresponding portion of the original N-bit vectors from memory for those blocks whose aggregate bits remain set to 1 after this intersection. This avoids blindly fetching all k blocks of each full bit vector.

To illustrate, imagine a single field $F_1$ has eight rules, so its bit vector is 8 bits wide: say 00001101 (bits numbered from left to right). If we use a block size A=4, we split this 8‐bit vector into two blocks of 4 bits each. None of the bits is set in the first block, 0000, so the aggregate bit is 0. In the second block, 1101, at least one bit is set, so the aggregate bit is 1. Hence, the aggregate vector is 01. If a packet matches this prefix and retrieves 01 as the aggregate vector, that tells us there may be matching rules in the second block but not the first. We only then fetch that second block (bits 1101) from the main memory for a precise intersection.

Assume that we need to classify the same packet as earlier with fields $F_1$ = 001 and $F_2$ = 010. The search for the longest prefix match on the respective tries yields the prefix 00∗ for $F_1$ and 01∗ for $F_2$. The aggregate bit vectors 11 and 10 associated with these prefixes are retrieved. A bitwise AND operation on these aggregate bit vectors results in 10. This indicates that the first block of the original bit vectors for the matching prefix of F1 and F2 needs to be retrieved and intersected. The first block for the matching F1 prefix is 1110, and the F2 prefix is 0110. The intersection of these two partial bit vectors results in 0110. The first bit set to 1 indicates the best matching rule, R2. Hence, the number of memory accesses required for the intersection of the original bit vectors is two, assuming the word size is 4 bits. This presents a savings of 50% when compared with the Lucent scheme, which requires four memory accesses. This is because the Lucent scheme requires accessing the second blocks of the original bit vectors for two fields.

Because each memory access can be expensive, reducing the number of blocks you must fetch can significantly improve performance. For instance, if each field’s bit vector is 50,000 bits wide but only a handful of bits are set, fetching and intersecting all 50,000 bits is wasteful. By first intersecting the much smaller aggregate bit vectors—perhaps each only 50,000 / 128 = 390–400 bits in size if you choose A=128—you can zero in on only those blocks likely to contain actual set bits. Of course, there is a potential for false positives: two aggregates might have a 1 in the same block, but when you look at the exact bits, there is no overlap. This means you might still retrieve the block (an extra step) only to discover that no actual rule matched that chunk. Nonetheless, the savings (fewer blocks fetched) outweigh these occasional false positives for many real classifiers.

Regarding complexity, ABV still employs the same underlying Lucent bit vectors of size N. However, doing a coarse “aggregate” intersection before retrieving the original blocks often reduces the memory accesses from O(N / w) to something more proportional to the fraction of blocks containing set bits. Since the number of bits set per packet is usually small, the intersection process can be much faster. Memory usage increases slightly because each field prefix stores the original bit vector and its aggregate version. Still, this overhead is typically modest compared to the gains in reduced access time.

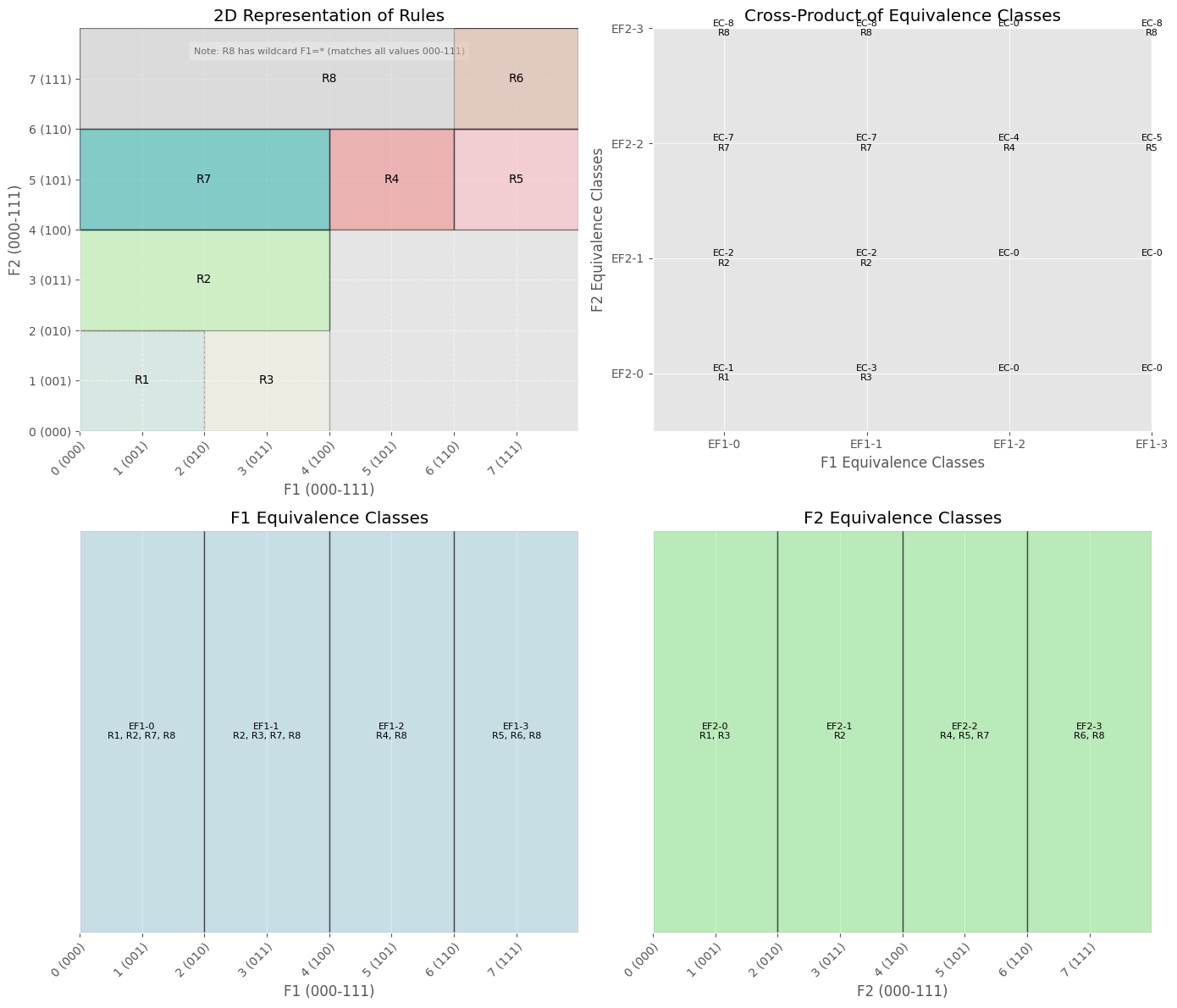

CROSS-PRODUCTING

Cross‐producting is a divide‐and‐conquer technique used in IP packet classification to find a packet’s best matching rule by independently searching each header field and then combining the results. To understand why this is helpful, think of each field (source address, destination address, or port number) as having a set of possible prefixes. When a new packet arrives, each field is independently matched against its LPM, LEM, etc. tables, returning the best match for that field. The cross‐product is then formed by taking these individual best matches—one for each field—and concatenating them into a single key. Once you have that single key (sometimes called C), you look up C in a precomputed cross‐product table that tells you the overall best matching rule for that packet.

Consider classifying the incoming packet with F1 = 000 and F2 = 100 values. Probing the independent data structures for the fields yields the longest prefix match for F1 as 00 and F2 as 10. These prefixes yield the cross product (00, 10). The cross-product is probed into table CT, which produces the best matching rule as $R_7$.

| Rule | $F_1$ | $F_2$ | $F_1$ Unique | $F_2$ Unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $R_{1}$ | 00* | 00* | 0* | 0* |

| $R_{2}$ | 0* | 01* | 00* | 00* |

| $R_{3}$ | 0* | 0* | 10* | 01* |

| $R_{4}$ | 10* | 10* | 11* | 10* |

| $R_{5}$ | 11* | 10* | * | 11* |

| $R_{6}$ | 11* | 11* | ||

| $R_{7}$ | 0* | 10* | ||

| $R_{8}$ | * | 11* |

| Number | Cross-Product | Best Matching Rule |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (0*,0*) | $R_{2}$ |

| 2 | (0*,00*) | $R_{2}$ |

| 3 | (0*,01*) | $R_{2}$ |

| 4 | (0*,1*) | $R_{8}$ |

| … | … | … |

| … | … | … |

| 29 | (*,10*) | … |

| 30 | (*,11*) | $R_{8}$ |

The rationale for doing this is rooted in the idea that if you are already performing the longest prefix match in each dimension (each header field), combining these results is enough to identify the rule that applies to all those dimensions simultaneously. If each field match is the “longest” possible, then tying them together through a cross‐product will point to the rule that best fits all fields at once.

Naively, if each of the $d$ fields has $N$ distinct prefixes, you could end up with $N^d$ possible cross‐products—far too large for practical storage when $d$ and $N$ grow. This leads to optimization strategies. One is to store only the cross‐products that appear in your classifier—sometimes called original cross‐products. If a cross‐product does not correspond to any real rule, it can be omitted, reducing memory consumption. Another optimization, known as on‐demand cross‐producting, builds entries only when needed by an arriving packet rather than precomputing everything in advance. Essentially, you keep a hash‐based cache of cross‐product results: when a new packet arrives, you compute its cross‐product key on the fly, look it up, and insert it into the cache if it is missing. The next time a packet arrives with the same key, you already have a fast lookup result.

Because you combine field matches in a single final lookup, cross‐producting can be implemented in hardware very efficiently by allowing parallel searches on each field. Each field search yields a label or identifier, which is concatenated to form a single index for the cross‐product table. If the table lookup finds a match, it returns the final rule that applies to the entire header. This approach can speed up classification dramatically, though it must be carefully designed to avoid exploding memory usage.

Recursive Flow Classification (RFC)

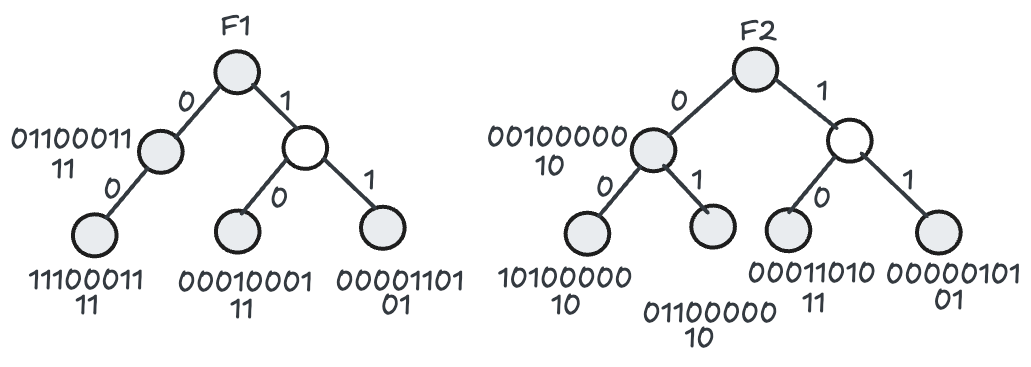

The key idea is to use equivalence classes on each field (or subset of fields) so that at each step, we deal only with identifiers for groups of values—rather than the values themselves—and then combine these group identifiers to determine the final rule.

Equivalence Classes: Imagine you have two packet fields, $F_1$ and $F_2$. In naive cross‐producting, you would list all possible prefix combinations in $F_1$ and $F_2$ and store them in a giant table. That can quickly become huge and impractical. RFC avoids this by grouping ranges or prefixes of $F_1$ that match the same set of rules into equivalence classes. As an example, suppose:

- For $F_1$, values 000 and 001 match the same rules, say $R_1, R_2, R_7, R_8$.

- For $F_1$, values 010 and 011 might match a different set of rules, say $R_2, R_3, R_7, R_8$.

RFC calls these two group equivalence classes because all values in a given group are treated the same for classification. Each equivalence class in $F_1$ is given an identifier, say $\text{EF1‐0}$ for the first class, $\text{EF1‐1}$ for the second, and so on. You would do the same for $F_2$, getting identifiers like $\text{EF2‐0}, \text{EF2‐1}, \dots$. When an actual packet arrives with a value of 000 in $F_1$, you look up which equivalence class that belongs to (in this example, $\text{EF1‐0}$), and then do likewise for $F_2$.

Multiple Steps Instead of One: RFC proceeds in a series of classification steps rather than a single giant cross‐product once you have these field-based equivalence classes. For instance, after you map a packet’s $F_1$ value to $\text{EF1‐0}$ and its $F_2$ value to $\text{EF2‐1}$, you look up ($\text{EF1‐0}, \text{EF2‐1}$) in a two‐dimensional cross‐product table that has been precomputed. This table tells you which equivalence class—call it $\text{EC2}$—the combination belongs to; $\text{EC2}$ represents the intersection of the rules that match $\text{EF1‐0}$ and $\text{EF2‐1}$. If needed, you can continue extending this process for more fields, always carrying forward a reduced set of matched rules encoded by an equivalence class identifier rather than the full rule list.

Example:

- One‐Dimensional Lookups: Suppose $F_1$ can be 000, 001, 010, …, 111. You group these values into four equivalence classes, each of which corresponds to a unique subset of matching rules. If a packet has $F_1$ = 000, you look up a simple table that says 000 → $\text{EF1‐0}$.

- Doing the Same for $F_2$: Suppose $F_2$ can also be 000, 001, 010, …, 111, grouped into four classes $\text{EF2‐0}, \text{EF2‐1}, \text{EF2‐2}, \text{EF2‐3}$. If the same packet has $F_2$ = 010, a table might say “010 → $\text{EF2‐1}$.”

| Rule | $F_1$ | $F_2$ |

|---|---|---|

| $R_{1}$ | 00* | 00* |

| $R_{2}$ | 0* | 01* |

| $R_{3}$ | 0* | 0* |

| $R_{4}$ | 10* | 10* |

| $R_{5}$ | 11* | 10* |

| $R_{6}$ | 11* | 11* |

| $R_{7}$ | 0* | 10* |

| $R_{8}$ | * | 11* |

- Combining in a Two‐Dimensional Table: Next, RFC uses a two‐dimensional cross‐product table D. One axis of D is the equivalence classes of $F_1$, and the other is the equivalence classes of $F_2$. For $\text{EF1‐0}$ and $\text{EF2‐1}$, D might say “$\text{EF1‐0}$ and $\text{EF2‐1}$ → $\text{EC2}$,” meaning that combining those two fields leads to equivalence class $\text{EC2}$.

- Mapping to a Final Rule: Finally, you can have another small table that says “$\text{EC2}$ corresponds to the final best matching rule $R_2$.” This is where the classification completes.

| Equivalence Class | Rules Matched |

|---|---|

| EC-0 | - |

| EC-1 | $R_{1}$ |

| EC-2 | $R_{2}$ |

| EC-3 | $R_{3}$ |

| EC-4 | $R_{4}$ |

| EC-5 | $R_{5}$ |

| EC-6 | $R_{6},R_{8}$ |

| EC-7 | $R_{7}$ |

| EC-8 | $R_{8}$ |

Because RFC breaks classification into steps, it reduces memory usage: we no longer need a single, massive table of all field combinations. Instead, each field is processed to produce a smaller set of equivalence classes, which are then combined in a structured, multi‐step way. This approach is especially valuable when the number of distinct prefixes or rules is large, because it avoids storing redundant or impossible combinations.

In short, RFC’s core trick is to look up simpler class IDs for each field and then iteratively combine those class IDs, rather than trying to juggle all rules for all fields in one shot. This keeps lookups fast and memory usage manageable while still guaranteeing the correct best matching rule is found.

Review of Bit-Vector Schemes, Cross-Producting and RFC

Bit-Vector Schemes (LBV/ABV): As we say, Bit-vector classification algorithms represent the set of matching rules for a given field value as a bitmask. A bit vector is produced for each field dimension where each bit corresponds to a rule (1 if the rule matches that field value, zero if not). The Lucent Bit Vector (LBV) method intersects these vectors from all fields – typically with a bitwise AND – to find rules that match on every field. This parallel bit-vector intersection inherently avoids enumerating cross-products; it computes the intersection on the fly. The downside is that the bit vectors can be very large (one bit per rule per field value) and sparse, leading to high memory usage. Aggregated Bit Vector (ABV) techniques improve on this by compressing and grouping the bit vectors. Rather than store a giant bit mask for every possible value, ABV stores aggregated vectors for ranges or prefixes of values that share the same set of matching rules. This significantly reduces memory footprint by exploiting the fact that many adjacent values map to the same subset of rules. The ABV approach still uses the same fundamental operation – parallel lookups per field and bitwise vector combination – but with data structures to compress and quickly retrieve these vectors.

Cross-Producting: This approach precomputes combinations of field matches across dimensions. It creates lookup structures for every possible pair/triple of field values (computing the cross-product of field criteria). While it converts multi-field lookups into simpler lookups, it suffers from severe cross-product explosion as rule sets grow – similar to the TCAM issue of multiplicative scaling. Memory usage grows exponentially with the number of fields or unique values, making it impractical for large rule sets.

Recursive Flow Classification (RFC): RFC (Gupta and McKeown, circa 2000) uses a multi-stage decision process to avoid one giant cross-product. It partitions the rule matching across multiple smaller lookup tables (each handling a subset of bits or fields) and combines partial results recursively. RFC can achieve very high throughput by precomputing intermediate results, but it requires extensive preprocessing and large memory to store those intermediate “chunks” of rule bit vectors. Essentially, RFC trades memory for speed: it avoids on-the-fly cross-product explosion by caching combinations in tables at the expense of potentially high memory overhead for large rule sets.

Juniper’s Express 4/5 Classification Architecture Overview

Juniper’s Express 4 and Express 5 ASICs use a packet filtering method based on a parallel decomposition strategy that resembles a hardware-optimized bit-vector (ABV) approach.

It’s worth acknowledging Juniper for openly sharing these architectural details rather than keeping them confidential or presenting their design as a mysterious black box.

Instead of a monolithic TCAM, the classifier is split into multiple lookup engines (facets) that handle one portion of the packet header in parallel. In Express 4, five such facets are operating concurrently: typically two for IP prefixes (source and destination), two for port ranges (source and dest ports), and one for smaller exact-match fields (protocol flags, TCP flags, etc.). Each engine uses a data structure tailored to its field type:

-

ALPHA (Absolute Longest Prefix Hash Algorithm): A custom longest-prefix address match engine. Facets 0 and 1 run the ALPHA algorithm to handle IPv4/IPv6 prefixes, MAC addresses, and similar fields requiring prefixes or exact matches. Instead of using conventional trie structures, ALPHA uses a single large hashed table of all prefix entries combined with clever tricks (caches, candidate length lists, Bloom filters) to test possible prefix lengths quickly. This design is more pipeline-friendly and efficient in hardware than a tree of pointers. ALPHA can perform longest-prefix lookups at high speed with lower memory and power by hashing possible prefixes and cutting down unnecessary probes. For example, it avoids traversing 128 levels for IPv6 by quickly eliminating prefix lengths that have no match via Bloom filters and caching recent lookups. The result of an ALPHA lookup for a given address is not a single rule but an index identifying all filter terms that matched that address field.

-

BETA (Best Extrema Tree Algorithm): A range matching engine for ports and other numeric ranges. Facets 2 and 3 implement BETA for source and destination port fields (and similar range-based fields). BETA performs a multi-way binary search on stored range boundaries (extrema) to determine which configured range(s) a given packet value falls into. The hardware uses a balanced 4-ary search tree (each node compares the value to up to 3 pivot keys, yielding 4-way branches) to cut the search depth in half compared to a binary tree. This structure can quickly pinpoint the matching range segment for a port number, even among many configured ranges. Each node comparison determines the direction of traversal according to straightforward numerical rules:

- If port ≤ extrema 1: Traverse the leftmost branch.

- If extrema 1 < port ≤ extrema 2: Traverse the second branch.

- If extrema 2 < port ≤ extrema 3: Traverse the third branch.

- If port > extrema 3: Traverse the rightmost branch.

The search returns an index corresponding to that range segment, which implicitly represents the filter rules whose port-range criteria cover the input value. In other words, if multiple filter terms have port ranges overlapping the packet’s port, the BETA search will land on a segment of the number line associated with all those matching terms. For example, if one rule covers ports 80–480 and another covers 240–960, an input port of 300 falls in the overlapping segment 240–480, which is tagged with an index representing both rules. Internally, the BETA engine organizes its search tree nodes in SRAM banks for parallelism and scale e.g.. Express 4’s implementation had eight banks of 1024 nodes each, supporting up to 24k distinct range endpoints, far exceeding typical requirements. Like ALPHA, the BETA lookup produces an index that encodes the set of matching terms for that field.

- TCAM (Ternary CAM) facet: While algorithmic structures handle most fields, Express 4/5 include a small TCAM-based facet (Facet 4) for fields like protocol flags, TCP flags, DSCP, or other miscellaneous exact or bitmask matches. These fields are often just a few bits or require matching arbitrary bit patterns, which a TCAM can handle efficiently on a small scale. By confining these to a single small engine, the design avoids the expense of a massive TCAM for all fields. The TCAM facet returns, similarly, an index or bit mask for matching rules that consider those small-field criteria.

Data Structures and Memory Layout: Each facet has its specialized table or tree in high-speed memory. For instance, the ALPHA engine uses a hash table storing all prefixes (with prefix-length tags), and the BETA engine uses an on-chip tree structure for ranges. The results from these facet lookups are term cover vectors stored in associated memory tables. A cover vector is a compressed bit vector indicating which filter terms are matched by the lookup result. Because each filter term corresponds to a one-bit position, a vector can mark all terms that could match, given the field’s value. These bit vectors tend to be very sparse (few rules match any particular precise value), which allows them to be stored in compressed form (using run-length encoding or pattern dictionaries) to save space. Rather than storing a full N-bit vector for every possible field value, the hardware groups values into ranges or prefixes that share the same vector and stores one copy of that vector in a table, referenced by an index. The facet’s search result (e.g., a tree leaf index or hash hit) acts as an index into this cover-vector table, which returns the compressed bit mask of matching terms for that field value.

Each facet performs its lookup and produces a term match vector in the hardware. Under the hood, each facet’s search results in an index into a cover-vector table. For instance, ALPHA’s prefix lookup returns an index pointing to a precomputed bitmask of all filter terms that have a prefix match on that particular prefix (or exact key). The hardware uses these indices to fetch the bit-vectors from on-chip memory. Because most lookups match only a few rules, these vectors are sparse and highly compressible; they use run-length encoding and pattern compression to store them efficiently.

A hardware combiner circuit performs a bitwise AND when all facet vectors are retrieved. This operation is fundamentally fast; for example, 256-bit or 512-bit words can be done in one or a few clock cycles. The final match vector represents all filter terms that match on every field. Finding the highest-priority match is finding the lowest-index ‘1’ bit in this vector (assuming term #1 is the highest priority). This is done by a simple encoder/priority-decode logic scanning from the high-priority end of the vector. The position of that bit gives the term ID, which indexes into an action table that holds the actions for each term. The action memory provides the instructions (drop, forward, count, mirror, remark DSCP, etc.), which the hardware then applies to the packet’s metadata or forwarding decision.

In summary, after the packet’s header fields are extracted and pre-processed, all five lookup engines operate in parallel on their respective keys. Each engine produces an index that fetches the corresponding bit vector of matching filter terms for that field. At this point, we have a bit-vector for each field dimension with ‘1’s marking the rules that match that single field. The next step is to combine these results to find rules that match all the criteria simultaneously. This is done by a bitwise AND of all the vectors to produce a single final match vector. A bit in the final vector is ‘1’ only if that rule’s criteria were satisfied in every field lookup, meaning the rule as a whole matches the packet. This bit-vector intersection mechanism is analogous to the classic bit-vector algorithm (LBV/ABV), implemented in hardware logic to occur within a cycle or two for all bits in parallel.

Tuple Search

A rule describes packets using fields like Source IP and Destination IP. Each field can be specified with different prefix lengths (e.g., ‘01*’ specifies two bits, “0*” specifies one bit). A tuple is simply a group of rules that have the exact same combination of prefix lengths.

For instance, if a rule specifies a Source IP prefix with two bits (like “10*”) and a Destination IP prefix with two bits (like ‘01*’), that rule belongs in the tuple (2, 2). We create separate, efficient lookup tables (hash tables) for each tuple. Each hash table only contains rules with precisely that tuple’s combination of prefix lengths.

When a packet arrives:

- Extract the relevant bits from each field (e.g., two bits from Source IP, two bits from Destination IP).

- Use these extracted bits as a key in the corresponding tuple’s hash table.

- Quickly check only those rules within that tuple.

By doing this, you avoid searching through all rules. Instead, you jump straight to the few rules that match the specific prefix-length pattern of your packet.

For example, Imagine rules defined over two fields, $F1$ and $F2$ (each simplified to two bits):

| Rule | F1 Prefix | F2 Prefix | Tuple |

|---|---|---|---|

| $R_1$ | 00* | 00* | (2, 2) |

| $R_2$ | 0* | 01* | (1, 2) |

| $R_3$ | 0* | 0* | (1, 1) |

| $R_4$ | 10* | 10* | (2, 2) |

If a packet with bits F1=10 and F2=10 arrives:

- You directly look into the tuple (2, 2) hash table, using key ‘1010’.

- Quickly find matching rules (like $R_4$).

Tuple Space Pruning

Tuple space pruning enhances the efficiency of tuple space search by selectively filtering out irrelevant tuples. Rather than probing every possible tuple defined by prefix lengths in each field, tuple space pruning quickly identifies only those tuples that could realistically match the given packet. This significantly reduces the number of necessary lookups, optimizing the packet classification process.

The pruning process begins with each relevant field’s longest independent prefix matches. Assume a scenario where a packet is evaluated based on multiple fields. For each field individually, you perform a standard longest prefix match—similar to how routers find the best match for destination IP addresses. For example, suppose field F1 has the value ‘010’, and the longest prefix match available is “0*”, which is one bit long. Concurrently, field F2 might have the value ‘100’, with the longest prefix match being “10*”, two bits in length.

Once these independent longest prefix matches are identified for each field, the next step involves intersecting these matches to find the relevant tuple combinations. Using our previous example, combining a one-bit prefix in F1 and a two-bit prefix in F2 would point to the tuple (1, 2). By identifying only this specific tuple as potentially matching the packet, all other tuples are pruned away, eliminating unnecessary checks.

To illustrate this more concretely, consider a simplified classifier with two fields (F1 and F2), each capable of having rules with prefix lengths of 0, 1, or 2 bits. Suppose the classifier contains rules corresponding to tuples (0, 2), (1, 1), (1, 2), and (2, 2). In a naive tuple space search, each of these tuples would be checked individually, requiring four separate lookups.

However, with tuple space pruning, if the longest prefix match for F1 is found to be “0*” (one bit) and for F2 “10*” (two bits), then the only relevant tuple is (1, 2). This pruned approach drastically reduces the complexity, requiring only a single hash table lookup for the identified tuple rather than probing all available tuples.

Practical example of TSS-Based Hardware Packet Classification

As we saw, Tuple Space Search(TSS) is a packet classification strategy in which rules are grouped based on prefix-length combinations across header fields. Each unique combination of prefix lengths forms a “tuple,” and rules with identical prefix-length combinations are grouped together. Each tuple is then implemented as an exact-match hash table, making lookups faster by limiting searches to fewer candidate rules.

However, traditional TSS can have performance issues, as each tuple (pattern combination) requires its own lookup. Large rulesets can create hundreds of tuples, significantly increasing memory access and reducing throughput.

Hybrid SRAM + TCAM Architecture

The architecture uses a hybrid of standard SRAM and TCAM to store classification rules, partitioning the rule set based on rule pattern frequency. In this design, most rules (those belonging to patterns with many rules) are stored in hash tables using on-chip SRAM, while the numerous patterns containing only a few rules are placed in a small TCAM. The rationale is that most distinct patterns appear infrequently (few rules per pattern) but would inflate the number of searches in a pure Tuple Space Search (TSS) approach. By offloading these “sparse” patterns to a limited TCAM, the exact-match engine (SRAM-based) handles the bulk of rules without probing hundreds of patterns. This keeps the number of SRAM hash lookups per packet low while significantly reducing overall TCAM size and cost. In operation, an incoming packet is first checked against the SRAM-based exact-match engine; if a matching rule is found and it is guaranteed final (no higher-priority overlapping rule), the result is returned immediately without consulting the TCAM. Only if no match is found in SRAM or the found match might be shadowed by a higher-priority rule in a TCAM-only pattern does the pipeline fall back to checking the TCAM. Because only a fraction of packets ever need to hit the TCAM, the TCAM’s bandwidth and power requirements are minimized. This judicious partitioning enables a faster, more area/power-efficient design than a traditional full-TCAM classifier while storing most rules in cheaper SRAM memory.

Hash-Based Exact Match Engine

A hash-based exact-match engine at the system’s core implements an optimized form of Tuple Space Search in hardware. This engine organizes rules by their field specification pattern (tuples of prefix lengths or wildcard positions). It performs a series of exact-match lookups on packet header bits, similar to classical TSS. However, to meet throughput demands, the design limits the number of hash lookups needed per packet to only a handful (on average $\leq 4$ lookups, worst-case $\leq 8$ in hardware). The hardware-friendly optimizations introduced ensure that packet classification can usually be completed after checking only a few hash tables. Notably, using a hash-based approach also yields fast update times – inserting or deleting a rule only requires updating an entry in a hash table with no global reconfiguration. The exact-match engine is built on on-chip SRAM, which allows flexible memory banking and pipelining. The implementation uses cuckoo hash tables for efficient lookups and inserts. The design instantiates multiple memory banks for these hash tables so that several lookups can be performed in parallel (or pipelined) each clock cycle. Overall, this exact-match engine stores and handles the majority of rules, leveraging standard SRAM technology for speed and scalability while keeping the per-packet lookup count low through algorithmic improvements.

Extended Rule Patterns (eRPs) and Rule Merging

To further reduce the number of distinct pattern lookups, the architecture introduces Extended Rule Patterns (eRPs) – a technique to merge multiple rule patterns into a single lookup unit. An eRP essentially generalizes the idea of a “tuple” by combining several similar rule patterns so that they can be checked with one hash table lookup instead of many. Crucially, the merging is restricted to patterns that differ in only a few bits, a design choice that (i) limits the potential for hash collisions and (ii) keeps the per-entry memory overhead low. If two or more rule patterns are almost identical (e.g., they match the same fields with slight differences in some prefix lengths or bit positions), they can be covered by one extended pattern.

Data Structure and Logic: Each eRP is implemented as a single hash table that covers multiple original patterns. To construct an eRP, the hardware forms an eRP mask representing the union of the merged pattern’s wildcards. Any bit that is a wildcard (x) in at least one of the constituent rule patterns is treated as a wildcard in the combined eRP mask. The hash key for a given packet is derived by masking out (e.g., zeroing) all those wildcard bits in the packet’s header fields. This key is then used to perform a single SRAM hash lookup that simultaneously covers all merged patterns. The hash table entry format is augmented to distinguish the original rules. Along with the base key, each stored rule entry carries a small tag for the bits that were “lost” by merging (the bits that were specific in the original rule but became wildcards in the eRP mask). The lookup hardware is logically extended to compare the incoming packet to each candidate entry’s tag (extra bits) and the hashed key. This ensures that a rule is reported as a match only if the packet matches both the hashed bits and the specific bits that the rule requires. Notably, this added per-entry compare logic is very lightweight – it involves only a few bits – and was found to be implementable at negligible circuit cost in the ASIC.