Hashing Strategies for Packet Processing

“It is not easy to become an educated person.” - Richard Hamming

Introduction

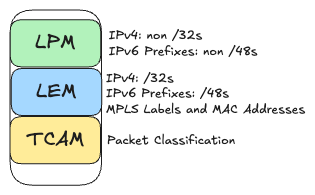

Exact-match lookups are among the simplest—and yet most critical—operations in data retrieval. The idea is straightforward: when you have a specific key, whether it’s a username, a dictionary word, or a network address, you need to find the one record that matches it exactly, with no partial matches. Think of it like searching a phone book: you know the exact name you’re looking for, and you stop once you find it.

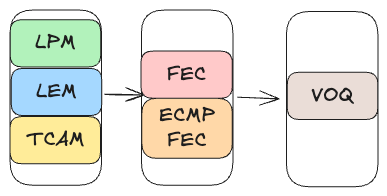

In the networking world, exact-match lookups are essential for operations like matching /32 IPv4 addresses, performing MPLS label lookups, and resolving MAC addresses. The diagrams below illustrate how a lookup table can be organized into three main buckets: Longest Prefix Match (LPM), Ternary Content-Addressable Memory (TCAM), and Longest Exact Match (LEM).

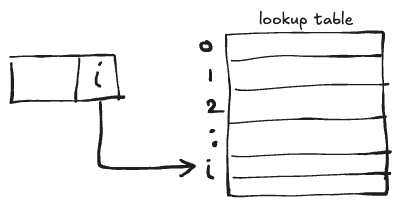

At first glance, it might seem that a simple lookup table indexed by a key—say, a /32 address or a MAC address—would suffice. However, this approach becomes impractical when dealing with very large keys or when combining multiple fields, such as a VRF with an IP address. That’s where hash tables come in. They transform a large or composite key into a fixed-size hash value, effectively condensing the vast key space into a much smaller, more manageable table. This simplifies storage and provides near-constant lookup times on average.

The main challenge is designing these tables to support line-rate traffic, ensuring that lookups occur fast enough for routers to process packets in real time without delay.

We will explore hashing by first reviewing the fundamentals, including key concepts like hash functions, load factors, and collision probabilities. Then, we’ll examine collision resolution techniques such as chaining, open addressing, and perfect hashing, discussing their advantages and trade-offs. Finally, we’ll cover advanced topics like multiplicative and universal hashing, cuckoo hashing, Bloom filters, and d-left hashing, focusing on their importance in hardware contexts with parallelism and bounded latency.

Hashing Fundamentals

Basic Hashing

Hashing is a technique that maps a key to a specific position in a table using two main steps:

1) Compute the hash value: Apply a hash function to the key to get a numeric value. $\text{hash} = \text{hashfunc}(\text{key})$

2) Determine the table index: Use the modulo operation to ensure the index fits within the table bounds. $\text{index} = \text{hash } \% \text{ array_size}$

This two-step process ensures that regardless of how large or complex the key is, it always maps to a valid position within the table. Often, the hash function and the table size are designed separately, with the modulo operation linking them.

Hash Function

The hash function is the heart of any hashing system. Its job is to spread the keys evenly across the table, which is crucial for fast lookups. A poor hash function that doesn’t distribute keys uniformly will lead to many collisions—instances where different keys map to the same table index—forcing the system to spend extra time resolving these conflicts.

Ensuring that a hash function distributes keys uniformly across a table is a challenging problem, often examined through statistical analysis. One important factor in this process is the size of the hash table. When resizing a hash table—usually by doubling or halving its size—it’s common to choose a power-of-two size. This choice simplifies the computation of table indices using fast bit-level operations.

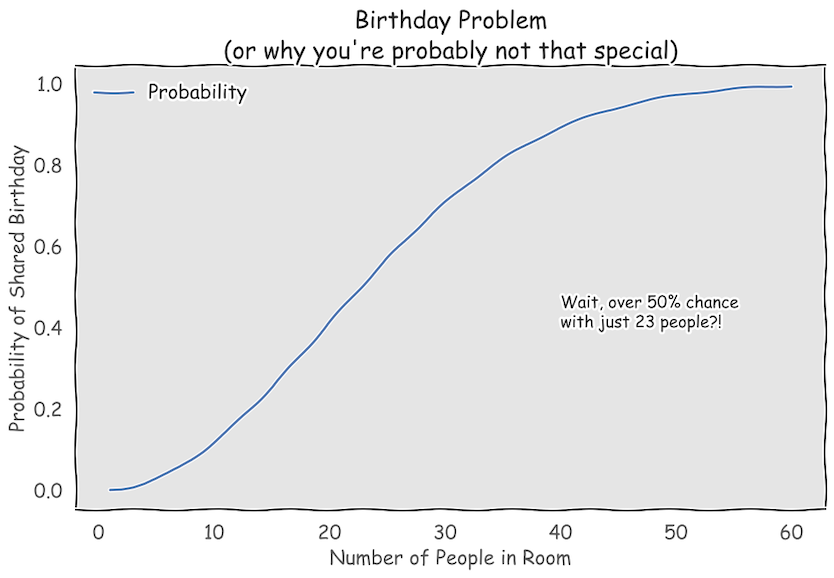

Birthday Paradox

The Birthday Paradox is a famous probability puzzle illustrating why collisions occur in hashing. It shows that in a group of just 23 people, there’s about a 50% chance that at least two people share the same birthday—a result that often defies our intuition.

Here is a simple breakdown:

- The first person can have any birthday, so the probability of having a unique birthday is: $\frac{365}{365}$

- The second person to have a different birthday than the first, the probability is: $\frac{364}{365}$

- The third person has a $\frac{363}{365}$ chance of unique birthday, and so on.

- Continuing this up to the nth person: $\frac{365-(n-1)}{365}$.

Calculating the Overall Probability:

Multiplying these probabilities together gives the chance that all n people have distinct birthdays:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{P(all distinct)} = \frac{365}{365} \times\frac{364}{365} \times \frac{363}{365} \times ... \times \frac{365-(n-1)}{365} = \frac{365!}{(365-n)!365^n}\]Thus, the probability that at least one birthday is shared is:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{P(at least one shared)} = 1 - \text{P(all distinct)}\]For n = 23, this probability is roughly 50%.

This paradox is especially relevant to hashing because it shows that even with a seemingly large number of possible hash values, collisions can happen with fewer items than one might expect.

LoadFactor

The load factor($\alpha$) is an important metric for hash tables, defined as $\alpha = \frac{n}{k}$. Where $n$ is the number of elements stored and $k$ is the total number of buckets. This ratio tells you how full the table is.

High Load Factor: When $\alpha$ is high, many elements end up in the same bucket, increasing the likelihood of collisions. More collisions mean that lookups take longer because multiple entries must be examined in a single bucket. To keep lookups fast, hash tables are typically resized when the load factor exceeds a certain threshold.

Low Load Factor: Conversely, if $\alpha$ is very low, the table is mostly empty. While this reduces collisions, it also wastes memory. The goal is to maintain a balanced load factor—enough to use memory efficiently, but low enough to avoid excessive collisions.

Balanced Distribution

Imagine a hash table with 4 buckets and 4 entries. If each bucket holds one entry, the load factor is: $\alpha=\frac{n}{k} = \frac{4}{4} = 1$. This balanced distribution ensures that lookups are fast since each bucket contains only one element.

Unbalanced Distribution

Now, consider the worst-case scenario where all 4 entries end up in the same bucket, while the other buckets remain empty. Even though the load factor remains $\alpha = \frac{4}{4} = 1$, the performance suffers because one bucket becomes a long chain, making lookups as slow as a linear search.

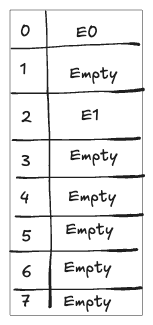

Too Many Buckets

If you increase the number of buckets without adding more entries, the load factor becomes very low. For example, with 8 buckets and only 2 entries: $\alpha = \frac{2}{8} = 0.25$. In this case, collisions are rare, but much of the allocated memory is unused, leading to inefficiency.

Collision Resolution Techniques

When using a hash table, you’re mapping many items into a fixed number of buckets (or slots). This inevitably leads to collisions—situations where multiple items land in the same bucket. The key questions are: How likely are these collisions to occur, and once they do, how can we handle them efficiently?

Probability of Collisions

When inserting $m$ items into a hash table with $n$ slots, collisions occur when two or more items map to the same slot. Here’s an intuitive breakdown followed by a formal derivation:

Intuitive Explanation:

- First Item: There is no collision because the table is empty.

- Second Item: There are $n-1$ free slots out of $n$, so the probability that it avoids a collision is $\frac{n-1}{n}$.

- Third Item: Assuming the first two items landed in different slots, the probability for the third item to avoid a collision is $\frac{n-2}{n}$.

- General Case: For the $m^\text{th}$ item, if all previous $m-1$ items are in distinct slots, the probability it avoids a collision is $\frac{n-(m-1)}{n}$.

Formal Derivation:

-

Probability All Items Are Collision-Free:

\[\hspace{5cm} P(\text{no collisions}) = \frac{n}{n} \times \frac{n-1}{n} \times \frac{n-2}{n} \times \cdots \times \frac{n-(m-1)}{n}.\]

Multiply the probabilities for each item:This can be written as: \(P(\text{no collisions}) = \frac{n \cdot (n-1) \cdots (n-m+1)}{n^m} = \frac{n!}{(n-m)! \, n^m}.\)

-

Probability of At Least One Collision:

\[\hspace{5cm} P(\text{collision}) = 1 - P(\text{no collisions}) = 1 - \frac{n!}{(n-m)! \, n^m}.\]

This result mirrors the outcome of the “Birthday Paradox”: even when $m$ is much smaller than $n$ , collisions can happen more often than we might expect.

Open Addressing

Open addressing is a collision resolution technique where, if a key’s designated slot is occupied, the algorithm searches for another free slot using a predefined probing sequence. Unlike chaining—where keys sharing the same hash value are stored in a linked list—open addressing stores the key directly in the table.

Linear Probing:

In linear probing, you compute the initial hash as $h = \text{hash(key)}$. If slot $h$ is occupied, you check the next slot $(h+1) \mod \text{tableSize}$ and

continue sequentially until you find an empty slot. For example, if a key $K2$ hashes to slot 1 (already occupied by $K1$), it checks slot 2 next; if key $K3$ also

hashes to slot 1, it continues to slot 3 if necessary.

Linear probing can lead to clustering, where adjacent slots become filled. To mitigate this issue, alternative methods such as quadratic probing and double hashing are employed. In quadratic probing, the probe sequence increases quadratically (e.g. $h + 1^2, h + 2^2,$ etc.), while double hashing uses a second hash function $h_2(\text{key})$ to compute the probe step as ($h + i \times h_2(\text{key})) \mod \text{tableSize}$ for the $i^\text{th}$ probe. Maintaining a low load factor (typically 0.5 to 0.75) is crucial; as the table fills, clustering intensifies, slowing lookups, and prompting the need for rehashing.

Perfect Hashing

A perfect hash function maps each of $n$ distinct elements to a unique slot, completely eliminating collisions. This is ideal for static key sets, such as compiler keywords or fixed dictionaries, where no updates occur over time. With perfect hashing, every lookup operates in O(1) time without the need for probing or chaining.

Two-Level Perfect Hashing (Fredman et al.):

- Level 1 – Partitioning:

- Choose a large prime $p$ and a random coefficient $k \lt p$.

- Define the first-level hash function as: $f(x) = ((k \times x) \mod p) \mod n$. This maps each key in the set $S$ into one of $n$ buckets.

- Group the keys into buckets based on their $f(x)$ value.

- Level 2 – Perfecting Each Bucket:

- For each bucket $i$ with $n_i$ keys, allocate a block of slots sized roughly $n_i^2$.

- Construct a mini perfect hash function $g_i$ for bucket $i$ that maps its keys into the allocated block without any collisions.

Example:

Consider $S = {10, 42, 7, 99, 55, 66}$ with $n = 6$. Suppose the first-level hash $f(x)$ distributes the keys as:

- Bucket 0: {10, 55}

- Bucket 1: {42, 66}

- Bucket 2:{7, 99}

- Buckets 3–5: Empty

Next, allocate disjoint slot blocks for each non-empty bucket (e.g., Bucket 0 gets indices 0–3, Bucket 1 gets 4–7, Bucket 2 gets 8–11). Then, define mini hash functions:

- For Bucket 0: $g_0(10) = 0$ and $g_0(55) = 3$.

- For Bucket 1: $g_1(42) = 5$ and $g_1(66) = 4$.

- For Bucket 2: $g_2(7) = 9$ and $g_2(99) = 10$.

To perform a lookup, first compute $f(x)$ to find the appropriate bucket, then use the corresponding $g_i(x)$ to directly access the final slot. This two-level approach guarantees $O(1)$ lookup time while keeping the overall space linear in $n$.

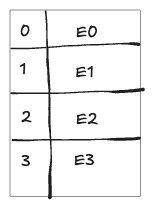

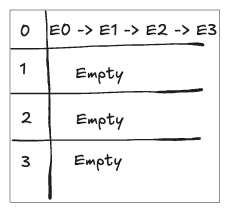

Chaining

One common method to handle collisions is chaining. Instead of forcing each bucket to hold only one item, chaining allows each bucket to store a list of items that share the same hash value.

Search/Insertion

- To insert, compute the hash, go to that bucket, then add the new key to the list.

- To search, compute the hash, and scan through the list in that bucket to find a matching key.

How It Works:

- Hashing: Compute the hash of the key to determine which bucket it should go into.

- Insertion: Place the key (and its associated value) into a linked list (or similar data structure) within that bucket.

- Multiple Items: If several keys hash to the same bucket, they are all stored in that bucket’s list.

In an ideal scenario, most buckets end up holding 0 or 1 items, and only occasionally do you see a small chain of collisions. However, if many items end up in the same bucket (resulting in long chains), lookup performance can degrade significantly, much like a linear search. In such cases, it might be more effective to improve the hash function or resize the table rather than overhauling the collision resolution strategy itself.

Multiplicative Hash

Multiplicative hashing computes the hash index using the formula:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{index} = \left\lfloor (n \cdot A \mod 1) \cdot m \right\rfloor\]Here, $n$ is the numeric representation of the key, $A$ is a carefully chosen constant (often around 0.618, derived from the golden ratio), and $m$ is the table size. The goal is to amplify small differences in key values into large variations in the resulting index, thus reducing clustering.

For instance, consider a table of size $m = 10$ and use $A \approx 0.618$ . For keys 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14, the computation is as follows:

| key n | n x A | Fractional Part | x10 | Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 x 0.618 = 6.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 x 10 = 1.8 | 1 |

| 11 | 11 × 0.618 = 6.798 | 0.798 | 0.798 x 10 = 7.98 | 7 |

| 12 | 12 x 0.618 = 7.416 | 0.416 | 0.416×10 = 4.16 | 4 |

| 13 | 13 x 0.618 = 8.034 | 0.034 | 0.034×10 = 0.34 | 0 |

| 14 | 14 x 0.618 = 8.652 | 0.652 | 0.652×10 = 6.52 | 6 |

This mapping—{1, 7, 4, 0, 6}—is more evenly spread out than using a simple modulo operation. For instance, a basic hash using $n \mod 10$ would map the keys to 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, which are much more clustered.

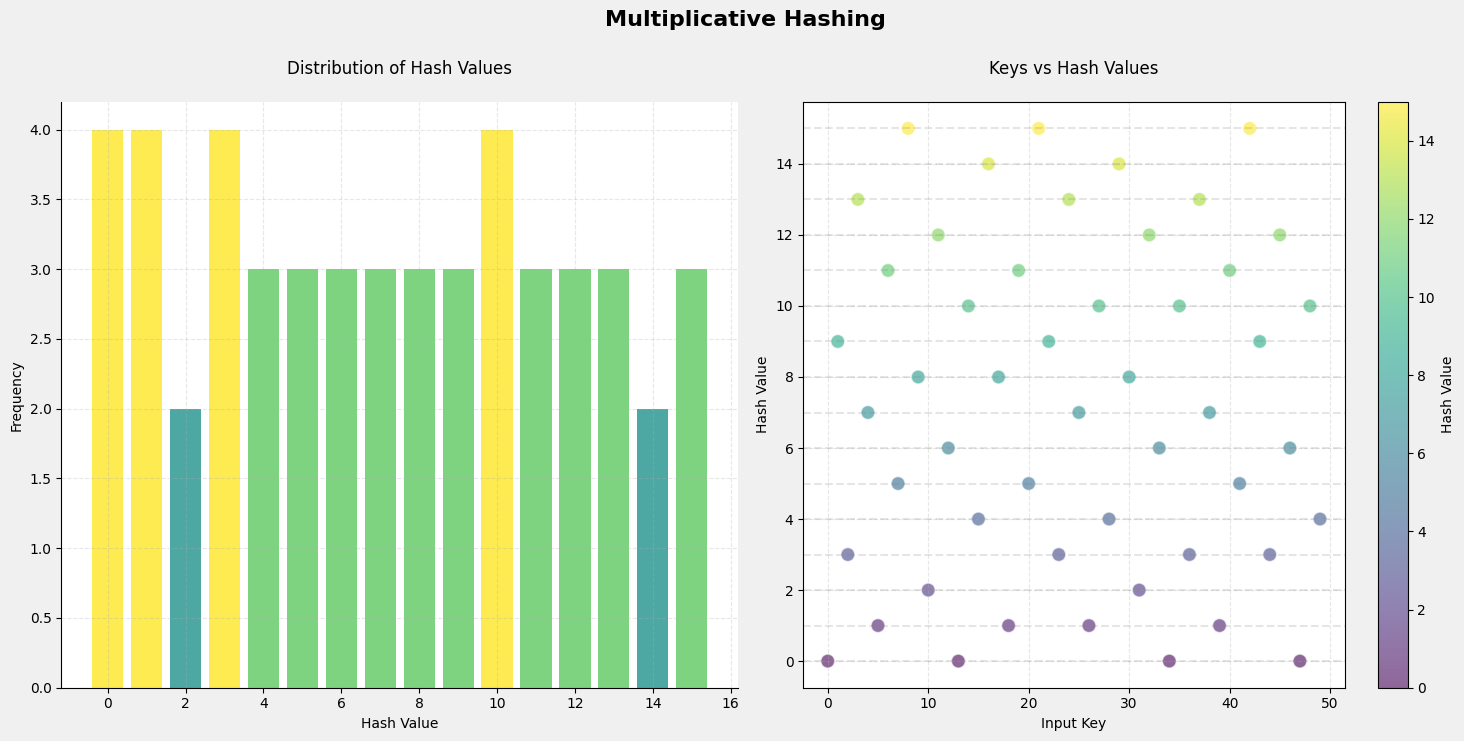

A plot from a simulation shows keys (0–49) evenly distributed across 16 table slots. The histogram summarizes the overall distribution, while the scatter plot details each key’s corresponding hash value, showing a balanced spread.

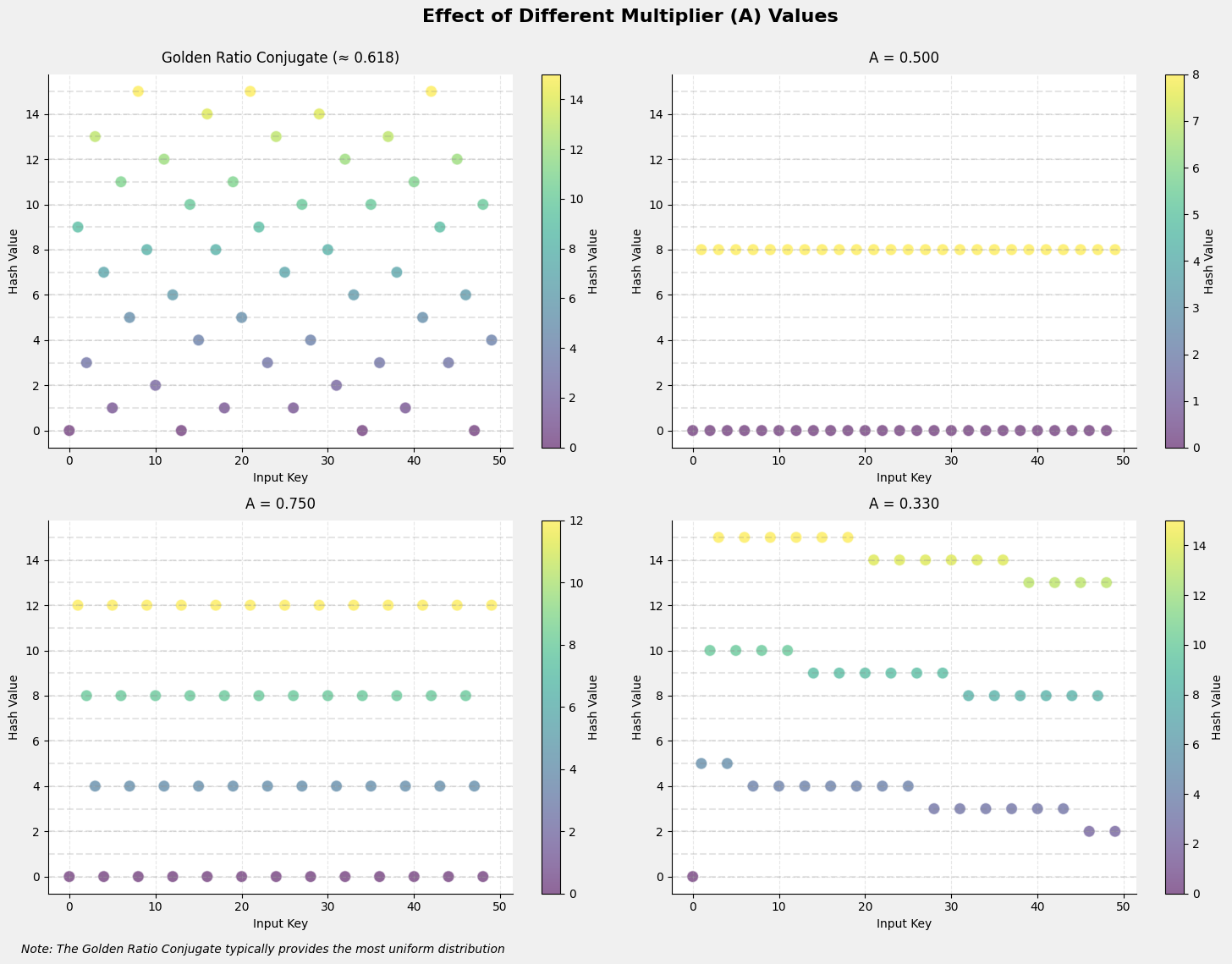

Another plot compares different constants $A$ for multiplicative hashing. The best distribution is achieved using the golden ratio conjugate, $(\sqrt{5}-1)/2 \approx 0.618$. Because this irrational number produces uniformly distributed fractional parts, it ensures that the hash values are well dispersed over the interval $[0,1)$.

Universal Hashing

Universal hashing employs a family of hash functions $\mathcal{H}$ such that a function $f$ is chosen at random before processing elements. This random selection ensures that for any two distinct keys $x$ and $y$, the collision probability is at most $\frac{1}{m}$, where $m$ is the number of buckets.

Key Properties:

- Collision Probability: For any two different keys $x$ and $y$ , if a function $f$ is chosen uniformly at random from $\mathcal{H}$, then

- Unbiased Selection: The random choice of $f$ ensures that no pair of keys is inherently more likely to collide than any other, even under adversarial conditions.

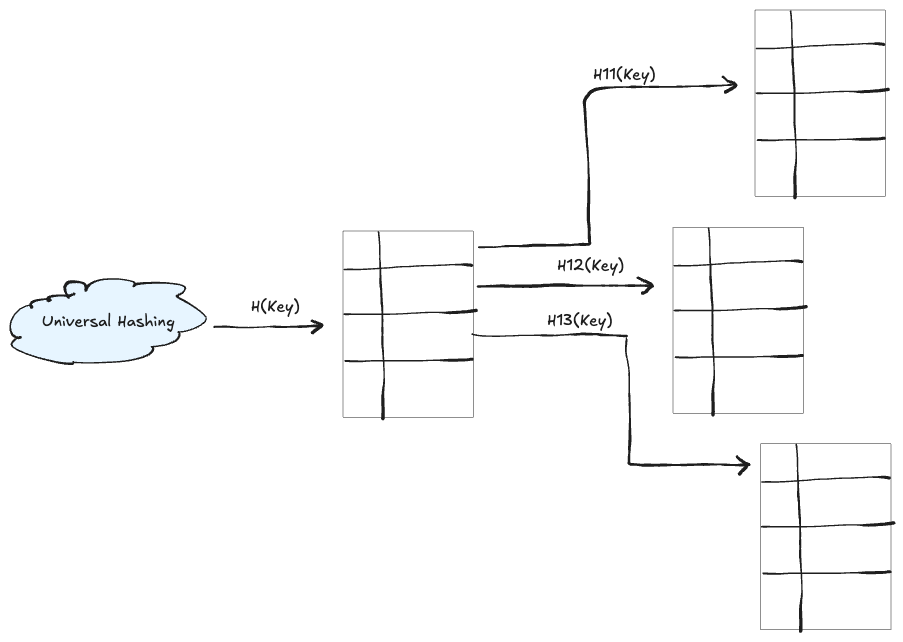

While universal hashing itself is a method for selecting a good hash function, many practical schemes extend this idea to a two-level structure. In these approaches:

- First Level: A universal hash function distributes keys into several buckets.

- Second Level: Within each bucket, a second universal hash function is used to resolve any remaining collisions.

This two-tier method is particularly common in perfect hashing for static sets, where the first level ensures an even distribution of keys, and the second level guarantees collision-free mapping within each bucket.

Cuckoo Hashing

Cuckoo hashing is inspired by how cuckoo birds displace eggs from other nests. In this method, each key has two possible “homes” in two separate tables. If you try to insert a key and its primary spot is already taken, you “kick out” the existing key and move it to its other home. This displacement may trigger a chain reaction, but in practice, these chains are short. If you ever get caught in an endless loop, you simply rebuild the tables with new hash functions.

Key Advantages:

- Fast Lookups: To find a key, you only need to check two spots—one in each table. This means lookups always take constant time.

- Efficient Inserts: Although inserting a key might cause a series of displacements, on average the process takes constant time. The rare cases where a loop occurs are handled by rehashing the entire table.

How It Works:

- Two Possible Locations: Each key can go in one of two spots, determined by two different hash functions.

- Insertion Process:

- Try placing the key in its primary spot.

- If that spot is free, you’re done.

- If it’s occupied, remove the existing key and place the new one there.

- Then, try to reinsert the displaced key into its alternate spot.

- Handling Loops: If this eviction process cycles (i.e., the same keys keep getting bumped), rehash the tables using new hash functions.

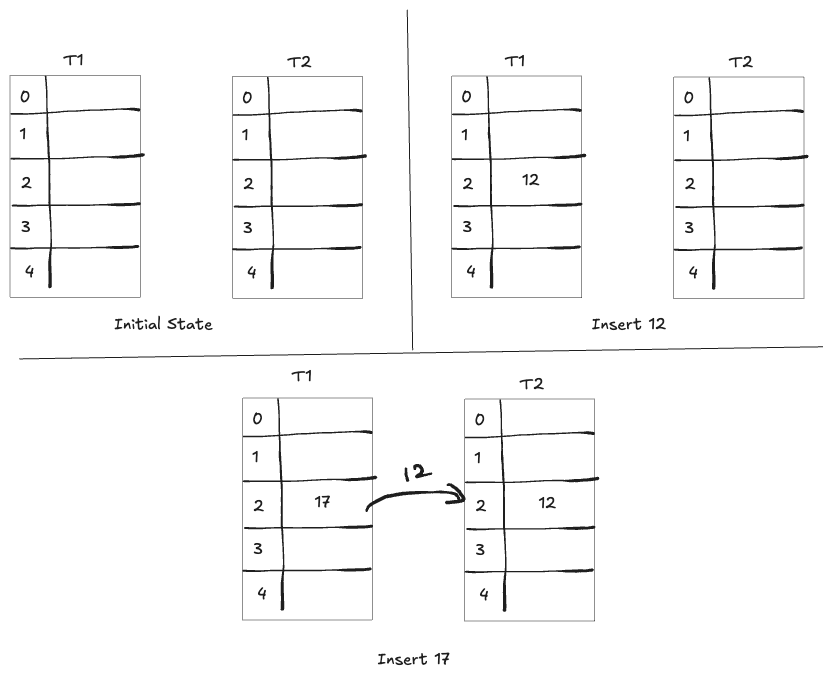

Example: Imagine two tables of 5 slots each, with hash functions defined as:

- $f(x) = x \mod 5$

- $g(x) = (3x + 1) \mod 5$

Insert x = 12 : $f(12) = 2$, Since $T_1[2]$ is empty, insert 12 there.

Insert y = 17 : $f(17) = 2$ as well. $T_1[2]$ is occupied by 12, so evict 12 and place 17 in that slot.

Now, compute $g(12) = 2$. Check $T_2[2]$ ; if it’s empty, place 12 there. This process continues, “bumping” keys between tables until every key is placed or a cycle is detected.

In summary, cuckoo hashing provides fast and predictable lookups with its two-choice scheme and handles insertions efficiently on average. The occasional need to rehash due to cycles is a rare event when using well-designed hash functions.

Bloom Filter

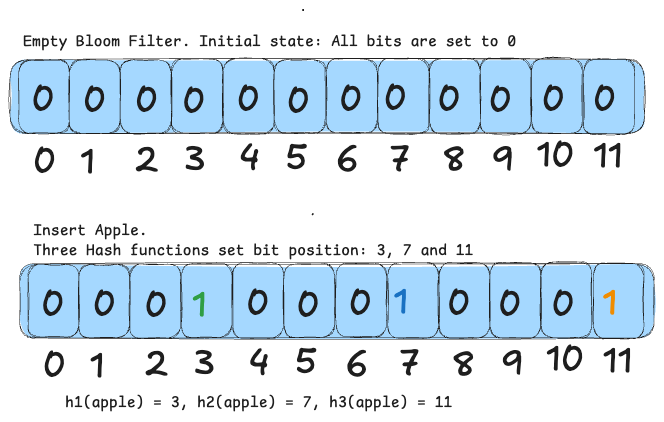

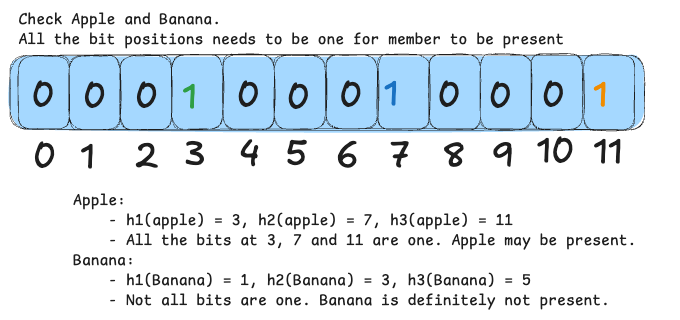

A Bloom filter is a space-efficient, probabilistic data structure used to quickly determine if an element is definitely not in a set or might be present. It works by maintaining an array of bits (all initially off) and using several hash functions. When an element is added, each hash function selects a bit position in the array, and those bits are turned on. To check if an element is in the set, you run it through the same hash functions and inspect the corresponding bits—if all are on, the element might be present; if any is off, it is definitely not in the set.

This method minimizes memory usage compared to storing every element, with only a small chance of false positives. Multiple hash functions help spread out the bits, reducing collisions. For example, with a 12-bit array and three hash functions, inserting “apple” might turn on bits at positions 3, 7, and 11. When checking “apple,” if all these bits are on, you conclude it could be in the set; if you check “banana” and find even one bit off, you know it has not been added.

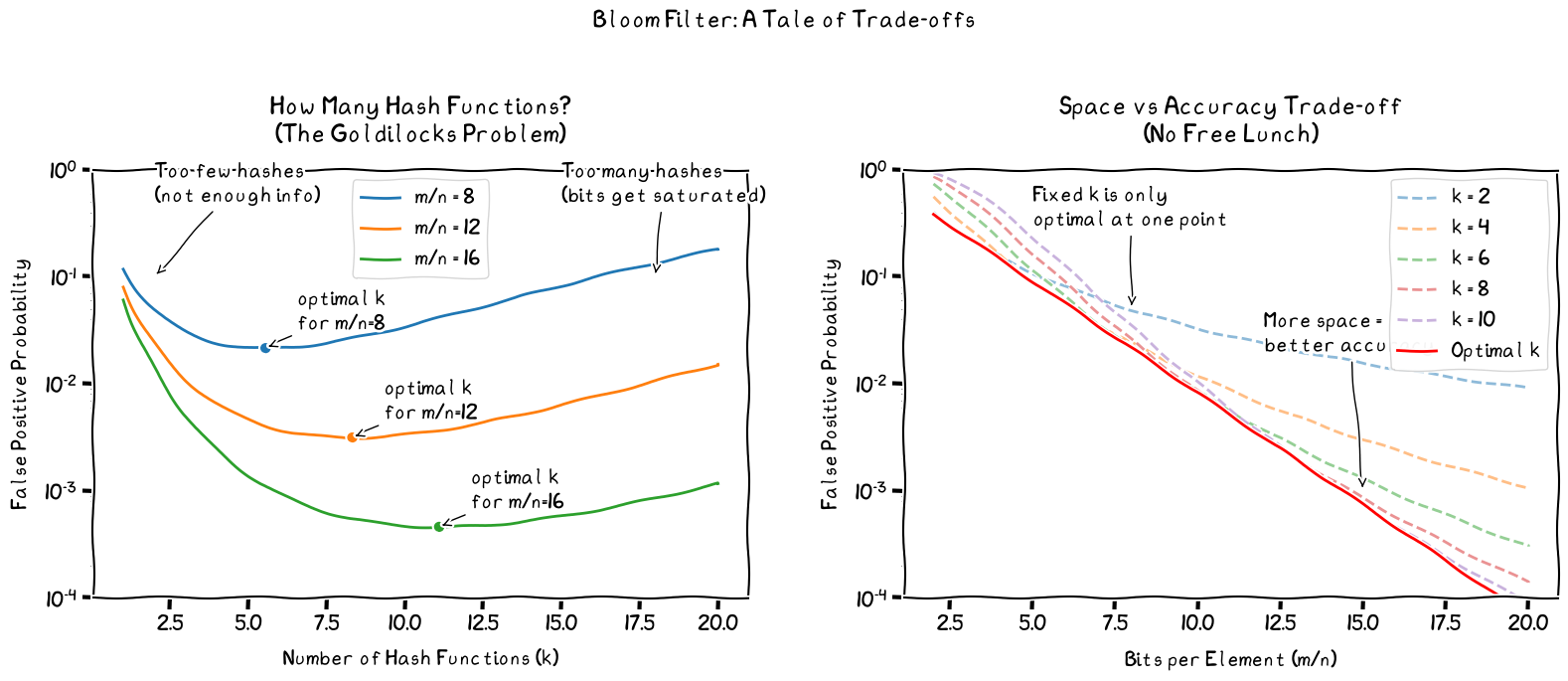

The practical performance of a Bloom filter depends on choosing the right size for the bit array (m) and the appropriate number of hash functions (k), based on the expected number of elements (n) and the acceptable rate of false positives. Let’s break down some details:

Uniformity Assumption:

We assume that each hash function distributes elements uniformly across the bit array. In other words, for any element inserted, every hash function is equally likely to select any of the m positions.

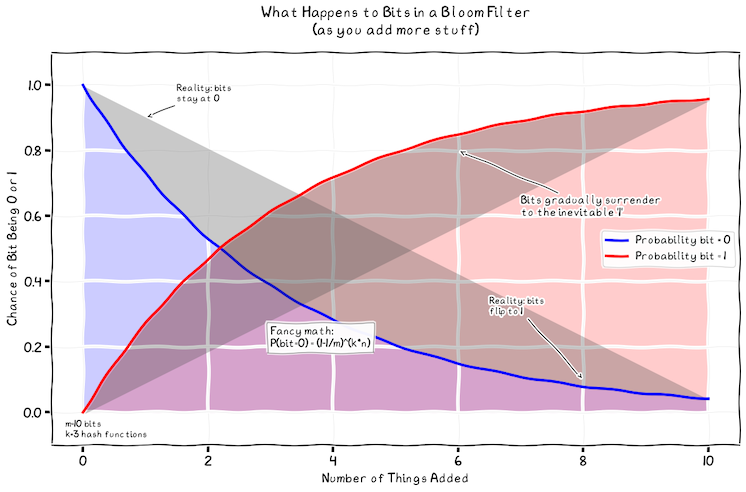

Probability That a Single Bit Remains Off After One Insertion:

For one hash function, the probability that it does not set a particular bit is:

\[\hspace{5cm} 1 - \frac{1}{m}\]With k independent hash functions used during a single insertion, the probability that a given bit remains off is:

\[\hspace{5cm} \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^k\]Probability That a Single Bit Remains Off After n Insertions:

Assuming independence across insertions, after inserting n items the probability that a specific bit stays off is:

\[\hspace{5cm} \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k \cdot n}\]Thus, the probability that the bit is set (i.e., becomes 1) is:

\[\hspace{5cm} 1 - \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k \cdot n}\]The below plot maps the probability of a bit being set as 0 or 1, as more things are added for 3 hash functions.

False Positive Probability

When you query an element that wasn’t inserted, the Bloom filter checks the k bits determined by its hash functions. If all these bits are 1, the filter indicates that the element might be present—a false positive. Assuming each bit is independently 1 with probability

\[\hspace{5cm} p = 1 - \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k n}\]false positive probability (FPP) for $k$ bits is:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{FPP} = p^k = \left[1 - \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k n}\right]^k.\]When m is large, the term

\[\hspace{5cm} \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k n}\]can be approximated by an exponential function. Using the approximation

\[\hspace{5cm} \left(1 - \frac{1}{m}\right)^{k n} \approx e^{-\frac{k n}{m}},\]This, we have:

\[\hspace{5cm} p \approx 1 - e^{-\frac{k n}{m}},\]and the false positive probability becomes:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{FPP} \approx \left(1 - e^{-\frac{k n}{m}}\right)^k.\]This exponential form is a standard approximation in mathematics, deriving from the limit $(1 - 1/x)^x \approx e^{-1}$ for large x.

How m, k, and n Affect False Positives

Increasing m (the number of bits): With a larger bit array and a fixed number of elements n, fewer collisions occur; hence, the false positive probability decreases.

Increasing n (the number of inserted elements): More insertions lead to more bits being set to 1, thereby increasing the likelihood that all k bits for a non-inserted element are 1, which raises the false positive rate.

Choosing k (the number of hash functions):

- Too few hash functions might leave many bits unset, reducing the filter’s accuracy.

- Too many hash functions can overly saturate the bit array, again increasing the chance of false positives.

There is an optimal value of k that minimizes false positives for a given m and n.

The Idea Behind an “Optimal k”

A Bloom filter is built using three main parameters:

- m: the total number of bits in the filter,

- k: the number of hash functions used, and

- n: the number of elements inserted.

Each time you add an element, all k hash functions set specific bits to 1. The optimal number of hash functions minimizes the false positive probability and is given by:

\[\hspace{5cm} k_{\min} = \frac{m}{n} \ln(2).\]This result is derived by differentiating the false positive probability with respect to k and finding its minimum. The factor $\ln(2) \approx 0.693$ arises from the exponential behavior of the bit-setting process.

Substituting the optimal $k$ back into the approximation for the false positive probability yields:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{FPP} \approx \left(1 - e^{-\ln 2}\right)^{\frac{m}{n}\ln 2} = \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{\frac{m}{n}\ln 2}.\]This can also be expressed as:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{FPP} \approx e^{-\frac{m}{n} (\ln 2)^2},\]or, equivalently,

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{FPP} \approx \left(0.6185\right)^{\frac{m}{n}},\]since $e^{-(\ln 2)^2} \approx 0.6185$.

Figuring Out m for a Desired False-Positive Rate

Often, you know the acceptable false positive rate p and the number of items n. A common formula to determine the required bits per element is:

\[\hspace{5cm} \frac{m}{n} = -\frac{\ln(p)}{(\ln(2))^2}.\]For example, if you aim for a false positive rate of 1% (p = 0.01):

\[\hspace{5cm} \frac{m}{n} = -\frac{\ln(0.01)}{(0.693)^2} \approx \frac{4.605}{0.480} \approx 9.585.\]You would typically round up to about 10 bits per element. With this, the optimal number of hash functions becomes:

\[\hspace{5cm} k_{\min} = \frac{m}{n} \ln(2) \approx 9.585 \times 0.693 \approx 6.64,\]which you would round to 7 hash functions.

Putting It All Together

- Decide on your target false-positive rate ($p$).

- Determine the number of elements (n) you expect to insert.

- Calculate the bits per element needed:

- Determine the total number of bits:

- Determine the optimal number of hash functions:

For each desired level of false-positive performance, you adjust both the size of the bit array (m) and the number of hash functions (k) so that the filter is neither under-saturated nor overly saturated.

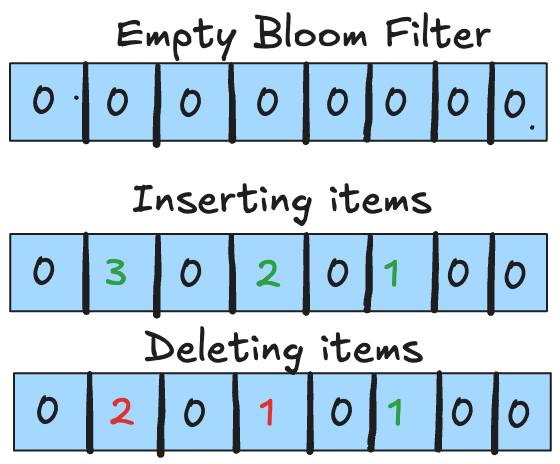

Counting Bloom Filters

One major drawback of standard Bloom filters is that they can’t reliably delete items. Since many items may share the same bits, simply clearing a bit to remove one item might inadvertently “delete” information about another item that also set that bit.

A common solution to the deletion problem is the Counting Bloom Filter. Instead of using a single bit per position, you store a small counter. Here’s how it works:

- Insertion: When you insert an item, each corresponding counter (determined by the hash functions) is incremented.

- Deletion: To remove an item, you decrement those same counters. A counter only resets to 0 when every item that contributed to it has been removed.

This approach neatly resolves the deletion issue. However, it introduces a new concern: counter overflow. Because each counter is typically a small integer (often using just a few bits), a heavily used position might exceed its maximum value. In practice, using techniques such as a Poisson approximation, it has been shown that 4 bits per counter are usually sufficient. The chance that any counter ever needs a value of 16 or more is astronomically small. And if a counter does overflow, additional mechanisms—like an overflow flag or dynamically increasing counter sizes—can be implemented as a failsafe.

Bloomier Filters

Taking the idea further, Bloomier Filters extend Bloom filters beyond a simple yes/no membership test. Instead of merely returning whether an item is in the set, a Bloomier filter is designed to store a small associated value (often a few bits) for each element. For items that aren’t in the set, it typically returns a special “null” value with high probability.

This functionality is especially useful when you need to retrieve extra information about each element—such as a tag, category, or short code—while still enjoying the space efficiency of Bloom filter-style hashing. Like standard and counting Bloom filters, Bloomier filters also have a very small probability of false positives, meaning that an element not in the set might occasionally return a non-null value. However, with appropriate sizing, this probability is usually negligible.

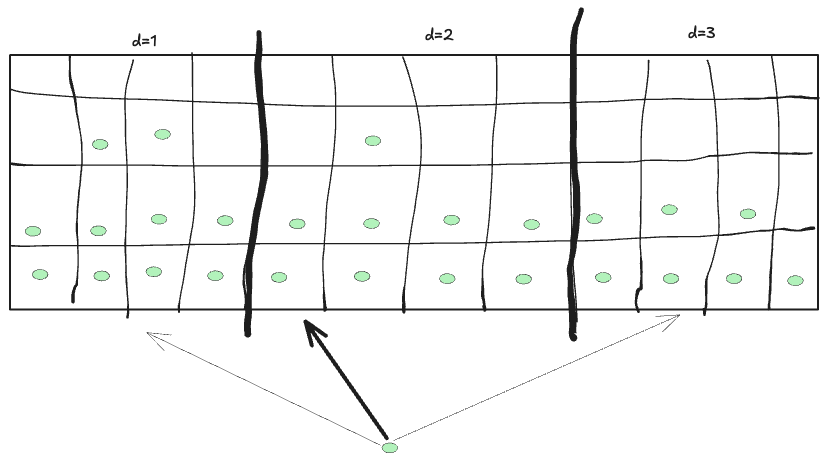

D-Left Hashing

In d-Left hashing, instead of relying on one hash function to map each key to a single bucket, it employs multiple hash functions. The overall hash table is divided into several distinct regions or subtables. Each subtable is associated with its own hash function. When you insert a key, you compute a hash for each subtable, and each hash function points to one specific bucket within its subtable.

Once you have these candidate buckets (one from each subtable), you select the best one to place your key. A simple strategy might be to choose the bucket that currently holds the fewest items. If there’s a tie, you might use a fixed rule—such as always picking the leftmost subtable—to break the tie.

This approach is an extension of the well-known “power of two choices” strategy. By giving each item multiple options (one per subtable), you significantly improve the chance that the item will be placed in a less crowded bucket, thereby reducing overall collisions.

The benefits of d-left hashing is reduced maximum load and better load-distribution. With d-left hashing, the maximum number of items in any bucket (the “load”) tends to be very low. In fact, with high probability, the maximum load is on the order of $\log \log n$ (where n is the total number of items). This is a dramatic improvement compared to the $\log n / \log \log n$ maximum load you might expect from traditional single-choice hashing. It also results in a very even spread of items among buckets.

Application of Hashing techniques

We have now discussed the fundamental concepts and challenges related to hashing. Next, I will shift to a practical perspective on how these techniques can be applied in high-speed networking hardware. I want to caveat that I am not a hardware design expert; my insights are primarily based on research and the information available to public. My goal is to provide enough context and understanding so that we at least know what questions to ask. Often, we aren’t even aware of the questions we should be asking.

Open Addressing with Fixed-Size Buckets

Previously, we discussed open addressing—a collision resolution strategy where all entries reside directly within the hash table array rather than in separate linked chains. When a collision occurs, the new item is placed in an alternate slot determined by a probe sequence (such as linear or quadratic probing) or by using a different hash function.

In networking hardware, open addressing is typically implemented using fixed-size buckets (also known as set-associative hashing). Here, each bucket holds a small number of entries (for example, one or four), and a lookup operation checks all entries in a bucket in parallel. This approach avoids pointer chasing and dynamic memory allocation—both of which are challenging to implement in high-speed ASICs. By constraining the bucket size, the hardware guarantees that each lookup will require only a bounded number of comparisons (e.g., at most four comparisons if each bucket holds up to four entries).

Key characteristics of open addressing in hardware include:

-

Fixed Bucket Capacity: Each hash bucket has a limited number of slots, often determined by the number of entries that can be accessed in a single memory read or clock cycle. If a bucket overflows, the hardware or control plane must address the issue—either by rehashing with a new hash function, using an overflow area, or evicting an existing entry (as in cuckoo hashing). In practice, hash tables are sized with enough spare capacity so that overflows are rare and can be handled separately.

-

Probe Sequences: A basic open addressing method is linear probing, where, if the intended bucket is full, the next consecutive slot is checked, and so on. However, pure linear probing can lead to unbounded probe chains in worst-case scenarios, which is not acceptable in hardware. To ensure predictable performance, designers either avoid linear probing by imposing strict limits on the probe length or employ alternative methods—such as double hashing, quadratic probing, multi-hash, or cuckoo schemes—to maintain time-bounded lookups.

Multiple-Hashing (d-way and d-left Hashing)

To reduce collisions and balance load, multiple-hashing schemes provide each key with several potential locations in the hash table. Instead of relying on a single hash function, these methods use d independent hash functions to generate d candidate buckets for every entry. Two commonly used approaches in this category are d-way hashing with chaining and d-left hashing.

d-way Hashing with Chaining: In this method, the hash table is conceptually divided into d parallel sub-tables. When inserting a key, it is hashed d

times (or with d different salts), resulting in d candidate buckets. The key is then placed in any bucket that has available space—typically by adding it to a

chain. During a lookup, all d candidate locations are checked (either in parallel or sequentially) until the key is found. Prior theoretical work shows that

even with just two choices (d = 2), the maximum chain length can drop exponentially compared to a single-hash scheme. In practice, using between two and

four hash functions already yields a significant improvement in the distribution of entries.

d-left Hashing (Multilevel): Designed with hardware efficiency in mind, d-left hashing divides the hash table into d equal segments arranged in order from

left to right, with each segment having its own hash function. For an insertion, the key is hashed once per segment, and the candidate buckets are examined in

sequence. The key is placed in the leftmost segment that offers an empty slot—a “first fit” approach. This strategy not only balances the occupancy across

segments but also minimizes the maximum load per bucket. If every candidate bucket is already full, the system recognizes that the table is too congested, prompting

the control software to trigger a rehash or expansion.

Why Multiple-Hashing is Used in Routers and Switches: The main advantage of multiple-hashing in networking hardware is the ability to perform bounded and

parallel lookups. In a d-left hash table, each of the d candidate positions resides in a separate memory segment or bank. This enables the hardware to check all

positions in parallel, resulting in a lookup that requires at most d simultaneous memory reads. The process is straightforward—hardware can compute all d hash

functions concurrently (or through pipelining) and issue parallel memory accesses—ensuring a constant-time lookup with no long probe chains and efficient memory utilization.

Cuckoo Hashing

Cuckoo hashing offers a significant advantage for hardware implementations by ensuring worst-case constant lookup times. In a 2-way cuckoo hash table, a lookup requires checking at most two locations (or k locations in a k-way variant), and these checks can be performed either in parallel or sequentially within a fixed number of steps. This guarantees that the lookup time remains constant regardless of the load, making cuckoo hashing ideal for exact-match tables such as MAC tables, IP route tables, or flow tables, where fast and deterministic performance is essential.

Implementation Considerations:

Parallelism: In hardware, cuckoo hashing is often implemented with separate memory banks for each hash function. For instance, a 2-way cuckoo hash table might use two SRAM banks so that both potential locations for a key can be read simultaneously, completing the lookup in one clock cycle. This is feasible because the hash functions are computed quickly, and the memory accesses are independent. While k-way cuckoo hashing (with k=3 or 4) is possible, most hardware designs stick with 2-way or 4-way due to complexity considerations.

Insertion and Updates: The insertion process in cuckoo hashing can involve multiple evictions, making it inherently sequential and more challenging to implement in high-speed hardware dataplanes. Consequently, dynamic insertions and deletions are typically managed by the control plane CPU or a background process rather than being handled directly during packet forwarding.

Memory Efficiency and Relocation: Cuckoo hashing generally achieves high load factors—often 80% or more—while still guaranteeing O(1) lookup times. However, as the table becomes nearly full, insertions may trigger a cascade of evictions or even fail if a cycle is detected. To address this, hardware designers usually provision extra capacity to keep load factors moderate and employ efficient rehashing strategies when necessary. ASICs can include small secondary tables or fallback mechanisms to handle the rare cases of insertion failure, ensuring that packet forwarding continues uninterrupted while the control plane can address the issue with a global rehash or expansion.

Bloom Filters for High-Speed Lookups

In networking hardware, Bloom filters are employed to accelerate lookups on large tables or slower memory by quickly eliminating keys that are not present. Some key applications include:

Distributed Tables and Caches: In some architectures, a large forwarding table is split between a small, fast on-chip cache and a larger, slower DRAM-based table. A Bloom filter is maintained for the larger table to quickly ascertain whether an item might be present. If the cache lookup misses, the Bloom filter is consulted before fetching data from DRAM. This ensures that if the item is definitely not in the large table, a slow DRAM access is avoided.

Packet Classification and ACLs: Bloom filters can also be used in packet classification engines. By assigning a Bloom filter to each category or segment of rules (such as those in access control lists), the system can swiftly eliminate entire groups of rules that do not apply to the packet, thus reducing the number of detailed comparisons required.

Hardware Implementation Considerations: Implementing Bloom filters in ASICs is relatively straightforward. They primarily require a large bit array and units to compute several hash functions. To achieve high-speed performance, the bit array is often partitioned across multiple memory banks, allowing parallel access to the necessary bits. Although the possibility of false positives means that an extra lookup might occasionally be triggered, this trade-off is acceptable when balanced against the benefit of avoiding unnecessary memory accesses. By allocating sufficient bits per entry, the false-positive rate can be kept very low.

In summary, Bloom filters act as efficient “traffic cops” for memory accesses in high-speed routers, directing lookups only toward those areas where a match is likely and significantly reducing both average and worst-case lookup times.

Hybrid Approaches

Modern systems often combine multiple strategies to leverage their individual strengths.

Hybrid TCAM + Hash Solutions: Rather than relying on a single lookup mechanism, some routers integrate both TCAM and hash-based approaches. For instance, a core router might use a small TCAM for complex ACL entries that involve wildcards and ranges—cases where hash tables struggle—while using a hash table for exact-match tasks such as MAC learning or ARP caching. Similarly, for longest prefix match (LPM), a router might reserve TCAM for the most critical or top few prefix lengths and deploy a hash or Bloom filter scheme for the remainder. This strategy minimizes the use of TCAM—which is both power-intensive and expensive—by confining it to specialized lookups, while the majority of traffic is efficiently processed by the hash table.

Hashing + Bloom (LPM Engines): Combining hash tables with Bloom filters creates a powerful LPM engine that significantly reduces the number of slow memory accesses. In this hybrid model, the Bloom filter quickly eliminates keys that are definitely not present, allowing the hash table to be queried only when a match is likely. This approach achieves performance comparable to that of large TCAMs but with far less on-chip memory and improved scalability. Although the update process becomes more complex—since both the hash table and Bloom filter must be managed—and the lookup behavior becomes slightly probabilistic (due to false positives), the improvements in speed and density are well worth these trade-offs.

Multiple Hash + Limited Chain (d-way with Small Chaining): Some implementations allow a small linked list within each bucket to handle occasional collisions that exceed the normal limit. For example, a hardware bucket might store up to four entries directly; if a fifth entry collides, it spills over into a tiny secondary linked structure in slower memory. This method is essentially a hybrid of open addressing and chaining: the primary hardware lookup is fast by checking the fixed number of entries, while an overflow flag signals the need to consult the secondary structure. Although this approach aims for near-100% table utilization without rehashing, the trade-off is that an occasional lookup may be slower. Due to these complexities, many hardware designers prefer strictly bounded schemes, often opting to oversize the table instead.

Pipeline-Aware Hash Table Design: An advanced consideration in hardware design is structuring hash algorithms to align with pipeline stages. For example, a 64-bit key might be split into two 32-bit segments, with each segment hashed in different pipeline stages and the results subsequently combined. While this approach doesn’t change the theoretical properties of the hash table, it distributes the computational load across multiple stages, thereby enhancing overall hardware efficiency. In some designs, part of the lookup—such as a Bloom filter check or partial index computation—occurs in one stage, with the remainder processed in subsequent stages. Although vendors tend to keep the specifics proprietary, the general objective is to ensure that no single hash computation or memory access exceeds the allotted time for its stage.

In summary, hybrid approaches are prevalent because no single technique is optimal in every scenario. We blend these methods to meet multiple objectives—speed, low memory usage, high load tolerance, and ease of updates—leveraging hashing as a core tool.

Pipeline and Parallel Lookups

Routers and switches achieve high throughput by processing multiple packets simultaneously through a series of hardware pipeline stages. Each stage might handle tasks such as header parsing, lookup operations, or counter updates. To incorporate hash-based lookups into this architecture, designers rely on two main strategies: pipelining the lookup operations and leveraging parallel memory accesses.

Pipelined Lookup Stages: When a hash table lookup requires multiple memory accesses—such as checking two potential buckets or first consulting a Bloom filter followed by a table lookup—these accesses can be divided among successive pipeline stages. For example, in Stage 1, the hardware computes the hash and reads from the first bucket; if necessary, Stage 2 handles the read for the second bucket. By overlapping these stages, while one packet is in Stage 2, another can begin in Stage 1. Although each packet might experience a latency of two cycles, the overall throughput remains one packet per cycle. ASICs break down operations into tightly timed steps, ensuring that no single lookup step becomes a bottleneck.

Parallel Memory Access (Multi-Bank): Hashing techniques such as d-way and cuckoo hashing are designed to exploit parallelism by distributing table segments across multiple memory banks. For instance, in a d-left hash table with four segments, the device attaches four independent SRAM blocks. A lookup then computes four hash values and issues four simultaneous reads—one to each bank—so that the overall lookup time is determined by the slowest of these parallel accesses. Even with a 2-way cuckoo hash table, duplicating memory or using dual-ported SRAM allows both candidate locations to be read concurrently.

Parallel Pipelines: ASICs incorporate multiple pipeline replicas that operate in parallel. Each pipeline can have its own copy of critical tables, reducing the per-pipeline load. For example, a switch might internally have four pipelines, each with its own hash table for MAC address lookups. Although the software view remains that of a single unified table, hardware partitioning ensures that memory access requests are distributed evenly.

Avoiding Stall Conditions: The effectiveness of pipelining depends on ensuring that each stage performs a predictable, fixed amount of work. Algorithms that require unbounded probing or have variable latency can disrupt the pipeline and cause stalls. Therefore, hardware hash tables are designed to execute a fixed number of memory operations—often in parallel—per lookup. If a lookup fails to find a result in the predetermined number of slots, it simply returns a miss without initiating further searches in the data plane. For example, if a key is not found after checking its two candidate cuckoo buckets, the packet is handled as unknown (e.g., flooded for a MAC address), and any necessary corrections are managed by the control plane.

Conclusion

In this primer, we have examined the fundamental concepts behind modern hashing techniques and their application in high-speed networks. We discussed various collision resolution strategies as well as specialized methods like cuckoo hashing. Each approach aims to balance speed, efficiency, and reliability, even under heavy load. I hope this overview has provided you with clear insights and a practical understanding of these methods. If you have any feedback, additional thoughts, or notice anything that could be improved, please feel free to reach out.

References

- Golden Ratio

- Mitzenmacher et al., Hash-Based Techniques for High-Speed Packet Processing, which discusses the adoption of d-left hashing and Bloom filters in router hardware.

- Kirsch et al., Using Multiple Hash Functions to Improve IP Lookups, which introduces d-left hashing and its parallel lookup advantage.

- PhD Thesis by D. Kim (CMU 2022) on programmable switches, noting that modern switch ASICs use variations of cuckoo hashing for exact-match lookups in SRAM and the concept of bounded linear probing for single-DRAM-access lookups.

- Advanced Data Structures: Theory and Applications

- Network Algorithmics