Notes on Flow Control for High Speed Networks

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” - Jan L. A. van de Snepscheut

Introduction

Flow control is a fundamental component in the design of high-performance networks. While reviewing the scheduling mechanisms used in router architectures, I took the opportunity to revisit the core principles of flow control, examine its various mechanisms, and reflect on their practical implications. This write-up outlines key models, compares typical schemes, and highlights relevant system-level considerations.

Principles of Flow Control

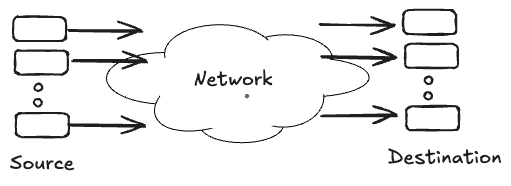

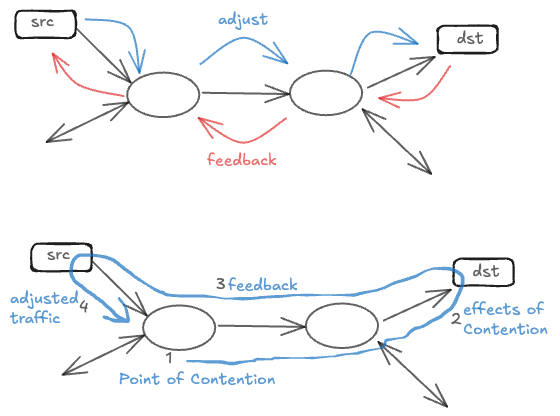

Flow control is a fundamental problem in feedback control for network communications. At its core, flow control addresses two critical questions that every network must solve: how do sources determine the appropriate transmission rate, and how do they detect when their collective demands exceed the available network or destination capacity? The solution lies in establishing effective feedback mechanisms from network contention points and destinations back to the sources, creating a self-regulating system that maintains network stability and performance.

The Fundamental Role of Round-Trip Time

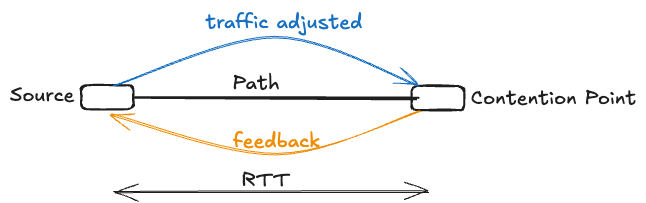

Round-trip time (RTT) serves as the fundamental time constant in any feedback-based flow control system. RTT represents the minimum delay that a source must wait before observing the effects of its transmission decisions. When a source begins transmitting, it will only learn about the impact of that transmission one round-trip time (RTT) after it has started. Similarly, when congestion occurs at a contention point in the network, the corrective effects of any feedback mechanism will only manifest at that contention point one round-trip time (RTT) after the congestion event occurred. This inherent delay creates what we call it as a “blind mode” transmission—a period during which sources must transmit without knowledge of current network conditions.

Lossy vs. Lossless Flow Control Paradigms

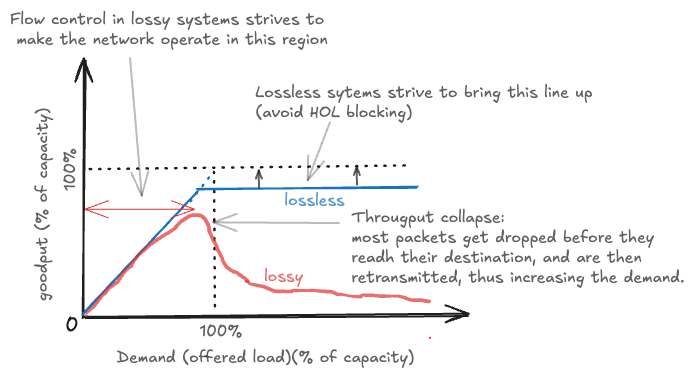

Flow control systems fundamentally divide into two paradigms, each with distinct characteristics inherited from different engineering disciplines. Lossy flow control, inherited from communication engineering traditions, accepts that buffer overflows may occur and packets can be dropped. While this approach appears simple, it introduces significant complexity. Lost data necessitates retransmissions, which waste valuable communication capacity and create a gap between goodput (useful data delivered) and throughput (total data transmitted). Maintaining satisfactory goodput under lossy conditions requires carefully designed protocols that can efficiently detect losses and orchestrate retransmissions without exacerbating congestion.

In contrast, lossless flow control guarantees that buffers will never overflow, ensuring no data loss occurs. This approach, inherited from hardware engineering where processors never drop data, eliminates wasted communication capacity and minimizes delay. However, lossless systems introduce their own complexities, requiring multi-lane protocols to avoid head-of-line (HOL) blocking and to break potential cyclic buffer dependencies that can create deadlock. The choice between lossy and lossless approaches profoundly impacts system architecture and performance characteristics.

Ref: Credit Based Flow Control

Classification of Flow Control Schemes

Flow control schemes can be classified along multiple dimensions, each representing different design choices and trade-offs. The first major distinction is open-loop, closed-loop and hybrid control. Open-loop admission control makes static decisions at connection setup time, while closed-loop adaptive flow control continuously adjusts during runtime based on current conditions. Within the closed-loop systems, we further distinguish between implicit and explicit feedback mechanisms, end-to-end vs. hop-by-hop control, rate-based versus credit-based approaches (including window and back-pressure mechanisms), and indiscriminate versus per-flow control.

Open vs. Closed-Loop Flow Control

Open-Loop Control

Open-loop flow control requires a source to request and secure network resources before initiating data transmission. After making this request, the source must await approval, incurring at least one round-trip time (RTT) of additional delay compared to closed-loop methods. Once approved, the source transmits at the allocated, reserved rate. While this approach guarantees predictable service quality, it comes with significant drawbacks. Reserved but idle resources cannot be dynamically reallocated to other users, potentially leading to poor resource utilization. Historically, open-loop control has its roots in telephony systems, inheriting a binary approach to resource allocation: either admit new flows at the risk of degraded quality for existing flows or refuse new requests entirely. This rigid model often feels outdated in modern data networks.

Key characteristics of open-loop control:

- Sources must explicitly request network or destination resources.

- Transmission begins only after receiving explicit approval, causing additional delay (at least one RTT).

- Guaranteed resources cannot be reassigned dynamically, potentially causing under-utilization.

Closed-Loop Control

Closed-loop flow control represents a fundamentally different strategy. Here, sources start transmitting data immediately without preliminary resource reservation. Instead, network resources are dynamically shared among active users based on priorities or weighted factors. Closed-loop systems significantly reduce initial delays and enable efficient resource allocation through statistical multiplexing.

Key characteristics of closed-loop control:

- Immediate transmission without prior approval.

- Dynamic allocation and sharing of network capacity based on prioritization and weighting mechanisms.

Hybrid Schemes

Hybrid flow control schemes aim to blend advantages from both open and closed-loop strategies. Sources reserve and receive guaranteed minimum capacities, providing predictable baseline performance. Beyond these guarantees, resources are dynamically allocated, ensuring efficient and flexible utilization of residual network capacity.

Key characteristics of hybrid schemes:

- Guaranteed minimum resource reservation for predictable performance.

- Dynamic sharing of remaining network resources.

Explicit vs. Implicit Feedback Mechanisms

Another crucial aspect of flow control design is the method of detecting and communicating network congestion. The two primary approaches are explicit and implicit feedback mechanisms, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Explicit Feedback Mechanisms

Explicit feedback mechanisms directly measure congestion within the network and communicate that information back to the sender using specialized signaling messages or headers. Instead of waiting for packet loss as an indirect sign of congestion, explicit methods proactively detect issues—such as rising queue lengths or increasing delays—and immediately inform data sources. This allows senders to quickly adjust their transmission rates, typically within a single round-trip time (RTT). Explicit feedback provides three key advantages:

-

Avoids packet loss: Because congestion is detected and reported early, senders can slow down before queues overflow. This reduces or eliminates the need for packet retransmissions, making data transmission more efficient.

-

Rapid reaction to congestion: Real-time congestion signals travel alongside regular data traffic, enabling senders to adjust their rate almost immediately. This prevents long delays caused by waiting for timeout-based detection methods.

-

Flexible rate control policies: Since explicit feedback does not rely on packet drops, network operators can independently design and tune rate-allocation strategies. For example, it becomes easier to implement fairness policies, prioritize latency-sensitive traffic, or guarantee minimum bandwidth to specific traffic classes without complicated drop configurations.

Practical implementations of explicit feedback include ATM’s ABR resource management cells, InfiniBand’s credit-based flow control, and modern ECN-based protocols.

Implicit Feedback Mechanisms

Implicit feedback mechanisms detect congestion indirectly, usually by noticing when packets are lost. Instead of directly measuring network conditions, the sender relies on missing acknowledgments (ACKs) or timeouts to identify congestion. While this approach is simple to implement, it has several limitations:

- Inefficient by design: Congestion must first cause packets to be dropped before the sender notices a problem. This results in unnecessary retransmissions, wasting network bandwidth.

- Delayed response: The sender must wait until a timeout occurs or duplicate ACKs are received, causing delays before corrective action is taken. This slow response reduces the effectiveness of congestion management.

- Unclear reason for packet loss: Implicit feedback cannot distinguish whether packet loss is due to congestion, faulty hardware, or transmission errors. This ambiguity complicates network troubleshooting and makes accurate adjustments difficult.

Explicit feedback avoids these problems by directly signaling congestion before packet loss happens. Although explicit methods are somewhat more complex to implement, they provide quicker responses, reduce wasted bandwidth, and deliver clearer insights into network conditions.

End-to-End vs. Hop-by-Hop Control

The scope of flow control presents a final major design choice. End-to-end flow control manages the flow between ultimate source and destination, providing a simpler implementation at the cost of longer feedback paths and slower response times. The extended feedback loop makes it practically impossible to guarantee lossless operation in end-to-end systems, as the amount of data in flight during the feedback delay can exceed available buffer capacity.

Hop-by-hop flow control manages flow between adjacent network nodes, enabling faster response to congestion and making lossless operation practical. However, this approach requires more complex implementation and coordination between nodes. The shorter control loops in hop-by-hop systems enable more precise control and better isolation between different network segments, but at the cost of additional protocol complexity and potential for control loop interactions.

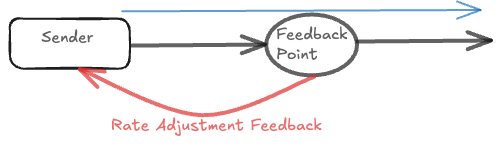

Rate Based Flow Control

In Rate-Based flow control, a contention point (switch, NIC, etc) measures some local metric that correlates with congestion (queue depth, output link utilisation, latency etc.) and feeds back a target sending rate or rate adjustment to the upstream sender. The sender then shapes its traffic so that its instantaneous departure rate follows that target.

Feedback style can be either Absolute or Differential. In the case of Absolute, Old rate($\lambda$) is replaced by new rate $\lambda_{new}$ (e.g. limit to X Gb/s), sender replaces current rate $\lambda \to \lambda_{new}$. In the case of differential, rate adjustment is like “Speed-Up by $\bigtriangleup$” or “Slow-down by $\bigtriangleup$”.

Absolute control converges in a single RTT is coarse; differential control is Lightweight on the wire and can track non-stationary traffic.

Simplistic Rate Based Flow-Control (ON/OFF)

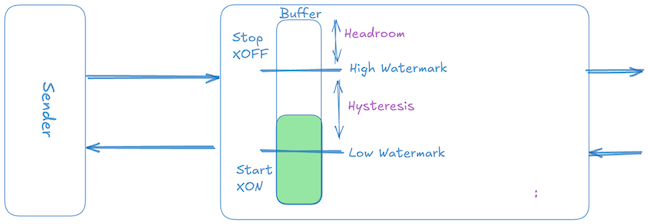

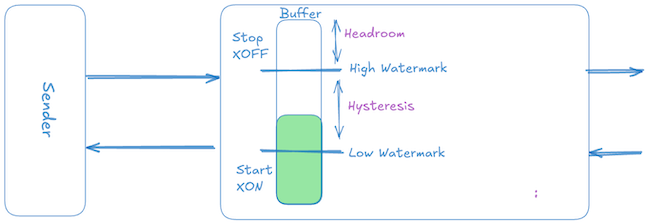

The simplest form of differential rate-based flow control is a two-level threshold-based scheme, commonly called ON/OFF or XON/XOFF flow control. Its operation is straightforward:

- When the receiver’s buffer occupancy hits a high watermark threshold, it sends an XOFF signal, instructing the sender to immediately stop transmission (sender rate $\to$ 0).

- Once the receiver buffer drains and occupancy falls below a lower low watermark threshold, it sends an XON signal, instructing the sender to resume transmission at the full, unrestricted rate (sender rate $\to$ peak).

Although this method is trivial to implement and widely used in standards like Ethernet Pause (802.3x) and Priority Flow Control (802.1Qbb), it is inefficient in terms of buffer usage. The inefficiency arises primarily because ON/OFF control signals are threshold-triggered rather than continuously updated based on precise buffer state, unlike credit-based flow control.

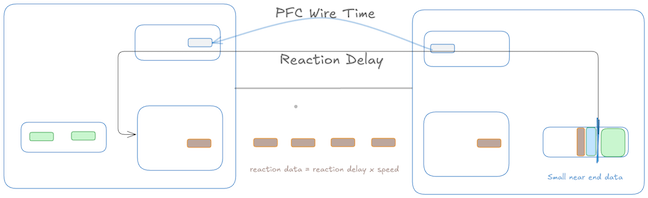

Propagation Delay Overshoot

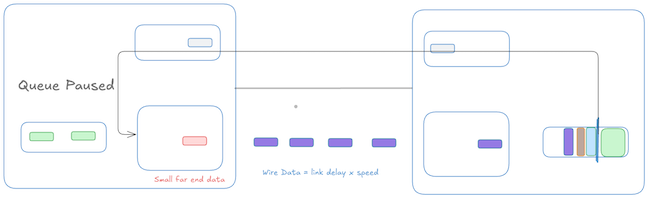

When the receiver’s buffer occupancy reaches the high watermark, it sends an XOFF signal. However, due to the propagation delay, the sender will continue to transmit packets until it actually receives and processes the XOFF signal. This delay leads to an overshoot in buffer occupancy, requiring sufficient extra space in the receiver buffer to accommodate packets already “in-flight.” We can look at this at a high level as a sum of Reaction data, Wire data and small far-end data.

Reaction Data: From the instant the near-end queue crosses $X_{off}$ until the far-end stops transmitting. This is basically time it takes to generate Pause frame, Traveling it back to the sender and the action time for the sender to pause the frame.

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{Reaction data} = R \times (T_{gen} + \text{Link Delay(One Way)} +T_{action})\]

Wire Data: The time after the last bit has left the far-end but has not yet reached the near end.

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{wire data} = R \times \text{Link Delay(One Way)}\]

There is some minor residual data from small far-end and near-end data which is in flight in addition to the reaction and wired data. So the total Headroom Buffer which needs to accommodated

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{HeadRoom}= \text{Reaction Data} + \text{Wire Data} + \text{Small near-end data} + \text{Small far-end data}\]Although for the sake of simplification, I am putting various components into big buckets of delays, one thing worth observing is that in both Reaction Data and Wire data, Link delay is a factor. As the link length starts growing, that becomes the dominating factor.

Hysteresis Margin to Avoid Oscillation

If we drop the pause as soon as the queue falls below $X_{OFF}$, the far-end starts transmitting again while local-queue still holds the residual bytes generated during the previous pause window, the queue can immediately re-hits the $X_{OFF}$ and we send yet another $\text{PAUSE}$. This will create oscillations between ON and OFF states also called as chattering.

To avoid rapid oscillation between ON and OFF states, the receiver does not resume transmission immediately upon dropping slightly below the high watermark. Instead, a significant gap—the hysteresis window—is deliberately maintained between the high ($X_{OFF}$) and low ($X_{ON}$) thresholds. Typically, this hysteresis window is generally another full Reaction Data worth of packets (or some % of Pause threshold), ensuring that by the time transmission restarts, the buffer occupancy remains comfortably below the high watermark, to maintain system stability.

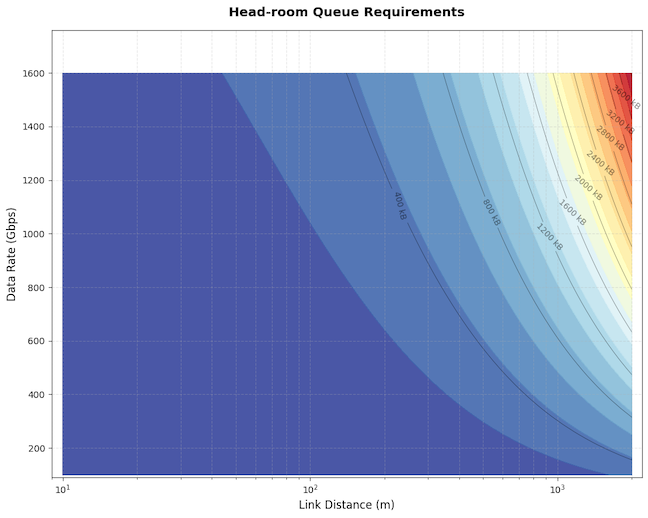

Impact of Link Delay and Rate

As we looked earlier that for headroom and the gap between XOFF and XON depends on the Reaction data and Wire data which are main contributors. As either distance or data rate increases, more bytes are “in flight,” requiring larger buffers to avoid packet loss.

The below plot shows that at shorter distances, buffer requirements are modest and dominated primarily by fixed silicon delays (interface and higher-layer delays), but as the link length or speed grows beyond a certain point, the buffer requirement dramatically increases, driven predominantly by the propagation delay (which adds additional bytes proportional to the bandwidth-delay product). The plot assumes MTU = 9,216 bytes, PFC/PAUSE frame size = 64 bytes, Interface Delay = 250ns, Higher-layer delays = 100ns.

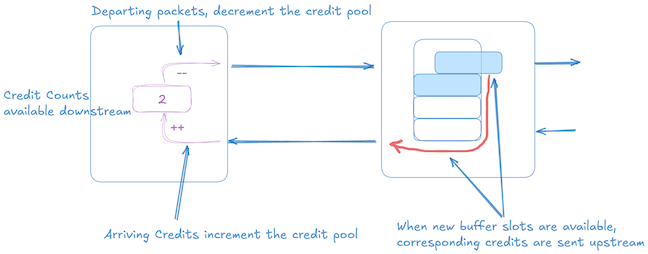

Credit-Based flow control

In credit-based flow control, communication occurs between a sender and receiver. Since the sender only learns about buffer availability at the receiver only after an RTT delay. To regulate transmission, the sender uses “credits,” with each credit representing space in the receiver’s buffer. Transmission is permitted only when the sender has available credits. Upon processing a packet, the receiver returns a credit back to the sender, signaling that buffer space has become available again.

So essentially RTT defines the control-loop delay, during this window sender’s view of the buffer is stale, so receiver needs to have enough space to hold every data injected by the sender in one RTT.

So one question arises here is, how big the buffer should be at the receiver to ensure that the communication remains loss-free and receiver has always enough data to keep its outgoing link fully utilized despite the presence of RTT delay. The answer turns out to be a buffer of one BDP is needed to keep the link loss-free while maintaining full utilization. At the sender, the data only leaves if a credit (representing a free slot) has already arrived. With $buffer \geq Rate \times RTT$, overflow is impossible even under abrupt stop/start conditions.

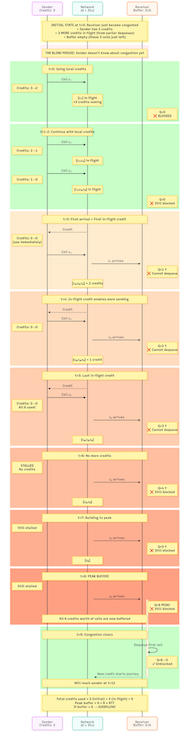

So let’s look at a toy example, by assuming:

- Link Rate = 1 cell/time unit (tu).

- One-way delay = 3 time units.

- RTT = 6 time units.

- BDP = Rate x RTT = 1 x 6 = 6 cells.

- Receiver Buffer = 6 cells.

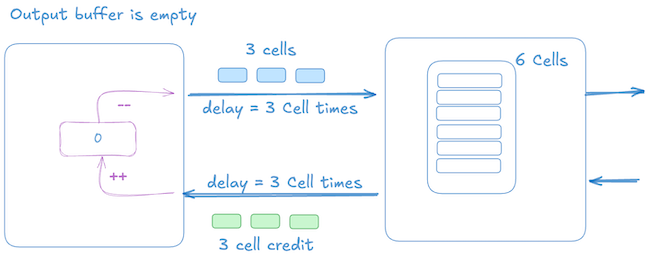

Initial state (t=0):

- Receiver has dequeued 3 cells, which has resulted in sending 3 more credits back to the sender. Receiver buffer is empty at this point, but the receiver has just become congested, resulting in no dequeue happening.

- Sender already has 3 credits from earlier dequeues.

The below picture shows that 3 cell credits are in transit and the sender has sent 3 data cells towards the receiver, and it’s credit count is 0.

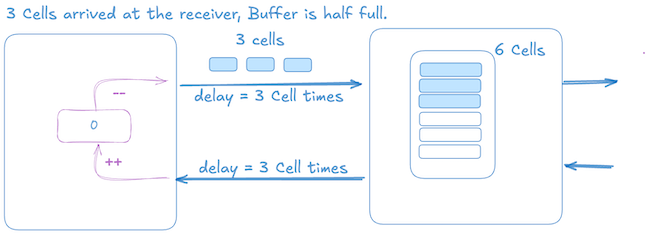

Once the 3 cells arrive at the receiver, sender also gets 3 more credits which results in injecting 3 more data cells, which receiver can accommodate, once full at this point the sender is stalled until it gets more credits.

Below is a time sequence diagram (“Click to enlarge”) which goes through all the events in more detail.

At time 6, buffer reaches 4/6 occupancy. The sender has consumed all 6 credits and sent 6 cells. This demonstrates why we need at least 6 cells of buffer - otherwise, cells arriving after time 6 would be dropped. A reader can play the same scenario with the initial conditions and with a buffer less than 6, and observe that it will result in a drop at the receiver.

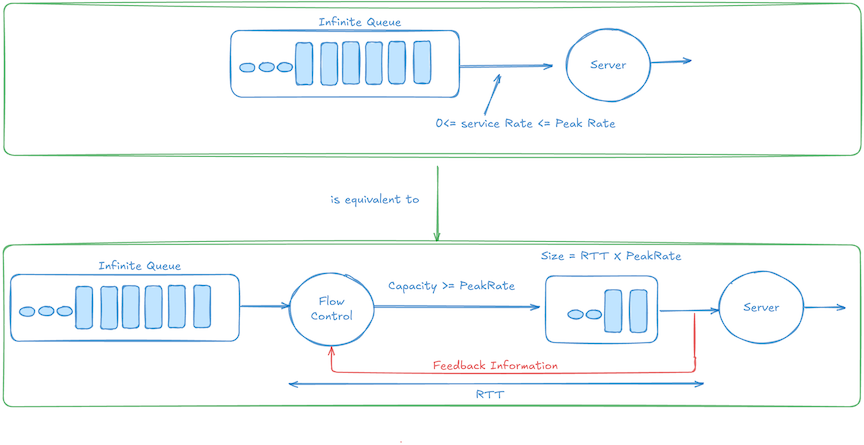

Infinite‑Queue Equivalence

For a link of rate R and round‑trip time (RTT), a receiver buffer protected by credit‑based flow control and sized to the bandwidth–delay product.

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{BDP}=R\times RTT\]is strictly loss‑free and is indistinguishable, from the sender’s perspective, from an infinite queue positioned immediately downstream.

The “infinite queue” upstream is a conceptual tool—this theorem says that a finite downstream buffer (with credits) behaves exactly as if the sender sees an infinitely large queue directly in front of it. If the downstream ever got full, this scenario never actually happens; instead, the sender slows down in advance (because credits stop arriving) making it look like the infinite buffer upstream simply “pushes back” the data, never overflowing downstream.

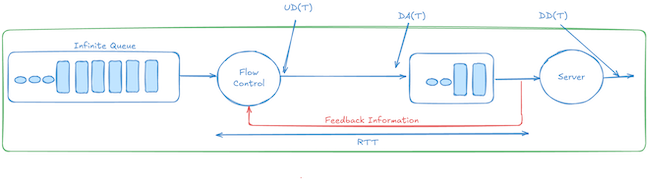

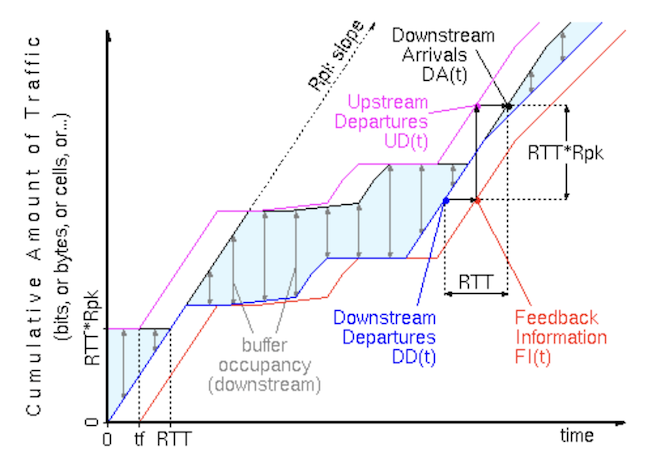

Let’s assume that we have:

- DD(t) – cumulative downstream departures physically exiting the downstream node up to time

t. - UD(t) – cumulative upstream (sender) departures up to time

t. it’s the data sent by the upstream node, and depends directly on credits returned after downstream departures. - DA(t) – cumulative data arrivals into the downstream buffer.

- Service‑rate constraint: $0\;\le\;DD(t+d)-DD(t)\;\le\;R\,d$. This is basically is that the amount of data exiting the node is less than or equal to $Rate \times d$, where is

d is the time delta between

t+dandt.

Ref: Credit Based Flow Control

Credit rule: At any instant the sender owns exactly the credits that represent free slots in the receiver buffer. Immediately after start‑up the sender holds $R\times RTT=\text{BDP}$ credits.

Upstream departures: Because the sender can transmit only when it owns credits, and each departure consumes one credit.

\[\hspace{5cm} UD(t) = DD(t - RTT) + RTT \times R\]At the start, sender has exactly $RTT \times R$ credits(This is the initial credit window). After initial credits are spent, new credits arrive exactly RTT time after downstream departs data. Thus, the total sent upstream at time “t” is the total departed downstream by (t - RTT) plus initial credits.

Downstream Arrivals: Since data takes exactly RTT to travel from upstream to downstream, we can say that Downstream Arrival function $DA(t)$ can be given as:

\[\hspace{5cm} DA(t)=UD(t-RTT)=DD(t-RTT)+R\times RTT .\]This means that the data entering the downstream buffer at time “t” corresponds exactly to the downstream departures one RTT earlier, plus the fixed initial credit window.

Buffer Occupancy: The occupied buffer can be represented as the difference between data packets arriving and data packets departing.

\[\hspace{5cm} BO(t)=DA(t)-DD(t)=R\times RTT-\bigl[DD(t)-DD(t-RTT)\bigr].\]The bracketed term $\bigl[DD(t)-DD(t-RTT)\bigr]$ is non‑negative and at most $R\times RTT$ by the service‑rate constraint, so

\[\hspace{5cm} 0\;\le\;BO(t)\;\le\;R\times RTT=\text{BDP}.\]Hence, the buffer never overruns, and from the sender’s viewpoint the system behaves as if any excess data were “pushed back” into an infinite upstream queue.

BDP Sufficiency & Necessity (Corollary)

The proof establishes that a buffer of exactly one BDP is sufficient for lossless operation. Conversely, if the buffer were any smaller, the worst‑case blind‑period injection of $R\times RTT$ bytes could overflow it, so the BDP size is also tight. This formalises the sizing rule introduced in Credit‑Based Flow Control and quantified with the toy example there.

Comparing Credit-based vs. XON/XOFF

So we looked at both credit-based and XON/XOFF flow control mechanisms. As the link distance or link rate or both increases, Credit based scheme requires less buffer than XON/XOFF scheme.

Credit-Based: The minimum buffer requirement is precisely one BDP, ensuring overflow is inherently prevented:

\[\hspace{5cm} B_{\min}=R \times RTT \quad(\text{one BDP})\]XON/XOFF: The buffer headroom for XON/XOFF includes three distinct components:

- Reaction Data: Bytes transmitted during pause frame generation, propagation, and sender pipeline drain. $R(T_{gen}+T_{link}+T_{act})$

- Wire Data: Bytes already in transit on the link. $R\,T_{link}$

- Hysteresis: Typically another full reaction-data segment to prevent frequent toggling (ON/OFF chatter).

The total buffer headroom requirement thus becomes:

\[\hspace{5cm} \text{HeadRoom} = R(T_{gen}+T_{link}+T_{act})+ R\,T_{link}+\text{Hystersis (Another reaction data worth of space)}\]Because both reaction and wire-data terms scale linearly with link length, the overall buffer demand for XON/XOFF increases faster than BDP over longer distances.

Flow Control in Switch ASICs

Why do we need Parallel Pipelines?

So assume that we want to build a 25.6 Tbps (32 x 400G) switch. This translates into packet processing rate of $\approx$ 38 billions pps for small 64-byte packets and $\approx$ 11.6 billion pps for 256 byte sized packets. If the switch asic is clocked at 1.2GHz, and 256B wide data bus, processing packets each clock cycle, a single pipeline can handle at most $\approx$ 1.2 billion pps. This mismatch results in mandating parallelism. So typically trade-offs are made where we give up line rate for small packet sizes to keep the number of parallel pipelines small and parallel pipelines with wider internal datapaths allows to process more packets per second to maintain the overall switch throughput.

Minimum Required Parallelism

A simple crude way to calculate the number of parallel pipelines we will need is by:

- Calculate the packet arrival rate.

- Calculate Single Pipeline processing rate.

- Calculate the number of Pipelines needed.

Calculate the packet arrival rate (R):

Packets on a link with a Bandwidth B bits per second, payload size S bytes, and overhead G bytes (includes

preamble, SFD, IFG etc.) arrive at an average rate given by:

Calculate Single Pipeline Processing Rate(r):

If each pipeline operates at a clock frequency $f$ (in Hz), has a datapath width W(in bytes), c is the packets per clock

cycle, and processes packets that requires multiple cycles if they exceed the bus width, the single pipeline processing rate

is:

Here, $\left\lceil(\frac{S+G}{W})/c\right\rceil$ represents the number of cycles required to process each packet, determined by the datapath width and packets per clock cycle.

Determine Required Parallelism (P):

To avoid packet loss, the number of parallel pipelines required is calculated as:

\[\hspace{5cm} P = \frac{R}{r} = \frac{B}{8(S+G)}\times \frac{\left\lceil(\frac{S+G}{W})/c\right\rceil}{f}\]If $P \gt 1$, multiple pipelines are required.

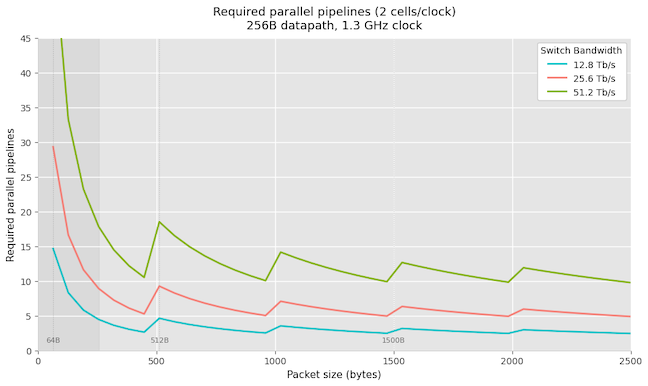

Below plot shows the number of pipelines needed, assuming 1.3 GHz, 256B databus for 12.8 Tbps, 25.6 Tbps and 51.2 Tbps.

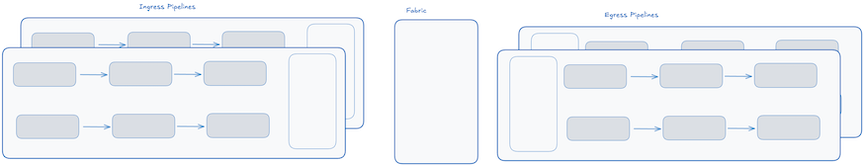

Here is an abstracted logical view of what it looks like. Some vendors will also refer to this as a slice.

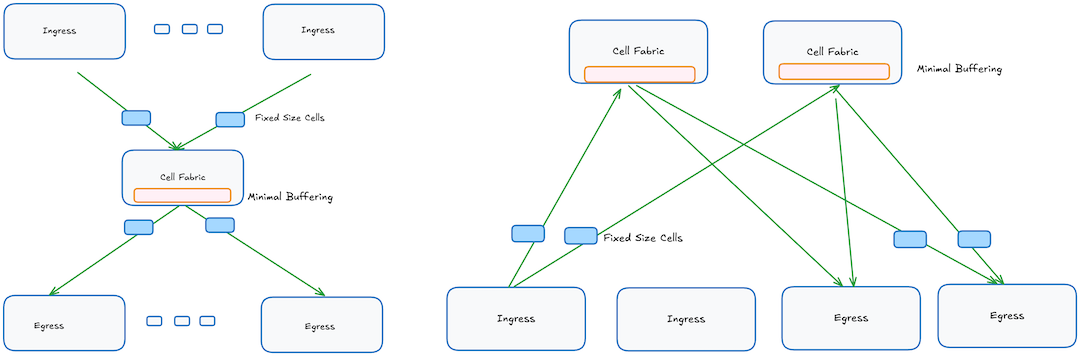

Flow Control between Ingress and Egress

This brings us to the flow control mechanism between the ingress and egress pipelines within modern switches. Broadly, these ASICs can be classified into two categories based on their internal memory architecture. Monolithic ASICs have ingress and egress sides that share a common memory domain. Due to this shared memory architecture, congestion and buffer occupancy can be effectively managed using simple threshold-based counters. In these switches, the scheduler can directly observe the occupancy state of each egress queue by checking local occupancy counters, removing the need for explicit flow-control messaging.

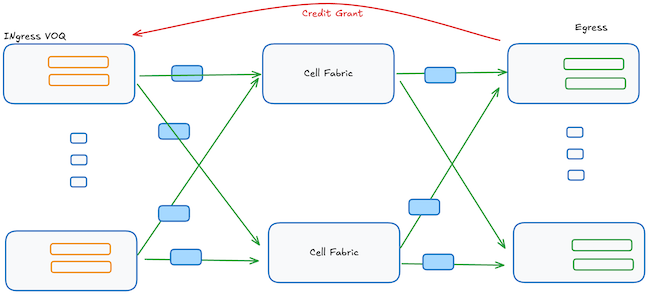

On the other hand, there is another category of ASICs designed for distributed-style switches, either as a single-chassis or distributed architectures like DSF/DDC. These ASICs distribute buffering and forwarding responsibilities across separate ASICs interconnected via a switching fabric. The internal fabric usually will have a speed-up, ex: jericho 2c+ has a 33% speedup. Since ingress and egress ASICs maintain separate memory domains without direct visibility into each other’s occupancy states, explicit flow-control communication becomes necessary. Typically, this is implemented using Credit-Based Flow Control (CBFC), where ingress ASICs transmit data only after receiving explicit credits (grants) from egress ASICs, ensuring data transmission never exceeds the available buffering capacity at the egress. A receiver grants explicit credits to the sender, each credit representing permission to send a fixed number of bytes, known as the credit quantum. Additionally, these distributed-style systems often route packets internally as fixed-size cells to simplify scheduling and improve efficiency. However, some implementations do not break the packets into fixed-size cells.

Below is an abstracted view where the egress scheduler gives a credit grant to the Ingress before it can send the data to egress. It’s also worth mentioning that having VOQ doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s using CBFC for flow control (ex: monolithic ASICs), as these two things are orthogonal, which folks sometimes confuse the two.

Credit Quantum Sizing

As we saw that the receiver grants explicit credits to the sender, each credit representing permission to send fixed amount of data, known as the credit quantum. One question is how big or small the credit quantum size should be. If it’s too small then it will lead to high control plane overhead, or if it’s too big then it could result in inefficient utilization.

A small credit quantum means each credit message covers fewer bytes, which requires the receiver to issue more frequent credit messages, placing a higher demand on the control plane resources. On the other hand, if the credit quantum is too large, may result in being inefficient.

The credit scheme, also need to make sure that it releases enough credit to account for the delay between the sender and receiver, and with no loss of throughput at the receiver. For example, let’s assume that we have:

- Clock rate: 1 GHz

- Credit issue rate: 1 credit every 2 clock cycles, 0.5G credits per second.

- Rate: 400Gbps (50 GBps)

- Fabric Speed-up: 1.05 (5%)

- Cell size: 256B

- RTT Control loop delay: .8 $\mu\text{s}$

So with the above the minimum credit rate needs to be at least $C_{min} = \frac{50 GBps}{0.5}= 100\text{B}$ to keep the port busy. If we account for 5% speed-up in the fabric, then its $105\text{B}$. Typical cell size is 256 Bytes, so we can round this to 256 Bytes per credit.

If the credits are given at a slice level and not port level, for example, let’s say 18 x 400G is one slice, then it will be $\approx 1800\text{B}$, which can be rounded to the nearest $2KB$ as the size of the credit. When sizing the credit quantum, some practical limits to keep in mind are: (1) the scheduler must issue credits fast enough to keep the pipe full, (2) on-chip counters must be wide enough to track all in-flight credits without roll-over, and (3) a small fabric speed-up is sometimes needed to mask any residual scheduler slack.

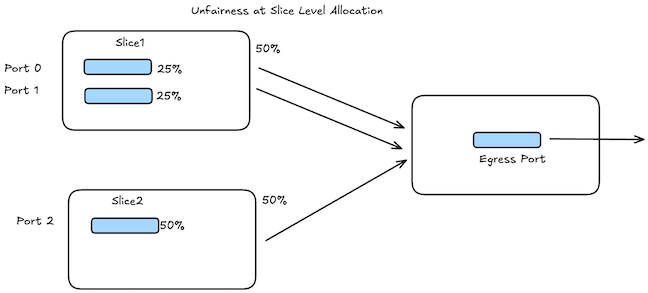

This does bring a fact that you have to be aware about how the credits are issued - Is it at a slice level or port level. If it’s at a slice level then it can result into unfairness.

Unfairness can happen at Slice level and this can be fixed by using Port level allocation though I think it will result in more control plane overhead in terms of credit message generation. It’s worth mentioning this more of how a scheduler is allocating a resource problem then the whole credit/grant system and is applicable to monolithic ASICs as well.

| Port | Expected | Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Port0 | 33% | 25% |

| Port1 | 33% | 25% |

| Port2 | 33% | 50% |

The worst amount of data which can be outstanding between ingress to egress will be ~1x BDP worth. Which in our example will be around 400Gbps (50 GB) x 800 ns = 40KB. Assuming 256B per cell, it is about ~156 in-flight cells. This also means the egress needs to have a small buffer worth at least ~40KB to ingest to avoid any drops.

Buffering in the Cell Fabric

The cell fabric whether it’s internal to a switch fabric or distributed chassis have some minimal buffering to handle the contention when cells from multiple inputs may compete for an output link. Shallow buffers are also important to provide minimal latency and jitter for the cells traveling the fabric.

The amount of buffering needed can be modeled by M/D/1 queueing model.

Intuition behind using M/D/1 Queuing Model

Imagine you’re at a toll booth on a highway. Each car represents a data cell arriving at an output link. Now, consider two different scenarios:

-

Scenario 1: M/M/1 queue

Cars (data cells) arrive randomly — that’s the Markovian (M) arrival process. The toll booth operator also processes each car in a random amount of time — sometimes fast, sometimes slow. This randomness in both arrival and service times makes the system highly variable. -

Scenario 2: M/D/1 queue

Cars still arrive randomly, but the toll booth operator is now a machine that takes exactly 60 seconds to process each car, no matter what. The arrival process is still Markovian, but service is Deterministic (D).

Now ask yourself: which scenario would we rather be stuck in as a driver? The second one, with the predictable machine, will always have shorter average queues. Why? Because unpredictability compounds. In the M/M/1 case, you might face a burst of cars and slow processing at the same time — a worst-case scenario. But in M/D/1, you remove one major source of randomness: the service time. This greatly improves queue behavior and average wait times.

This is exactly what happens with a cell-based switching fabric. Cells may arrive randomly from multiple ingress points, but because each cell has a fixed size, the time to transmit each one is deterministic. That is, the service time is constant. This deterministic behavior in transmission mirrors the M/D/1 scenario. By eliminating variability in service time, the system maintains shorter queues and better overall throughput — even under bursty traffic conditions.

Why Deterministic Service Helps

As we mentioned earlier, in an M/M/1 queue, you have two sources of randomness fighting each other. The queue length at any moment depends on the accumulated difference between random arrivals and random departures. It’s like taking a random walk where both your forward and backward steps are random; we can wander quite far from the origin.

In an M/D/1 queue, you’ve replaced one random process with a deterministic process. Every tick, exactly one customer leaves (if there’s anyone in the queue). The only randomness comes from arrivals. This is like a random walk where you always take exactly one step backward each time unit, but take a random number of steps forward. We will still wander, but much less wildly.

Mathematically, this manifests as the average queue length being exactly half in M/D/1 compared to M/M/1. For instance, if utilization $\rho = 0.9$, an M/M/1 queue averages 9 customers waiting, while M/D/1 averages only 4.5.

Queuing result comparison between M/M/1 and M/D/1, where $\mu$ is the service rate, $\lambda$ is arrival rate and $\rho$ is $\frac{\lambda}{\mu} (0 \lt \rho \lt 1)$.

| Metric | M/M/1 | M/D/1 |

|---|---|---|

| Avg. Queue Length | $\frac{\rho^2}{(1-\rho)}$ | $\frac{\rho^2}{2(1-\rho)}$ |

| Avg. Waiting time | $\frac{\rho}{(\mu-\lambda)}$ | $\frac{\rho}{2\mu(1-\rho)}$ |

Tail probability behavior

Typically, we don’t just care about average behavior; we also care about rare events. What’s the probability that the queue exceeds some large value N? This helps in determining for example, how much buffer memory we need to avoid dropping cells.

Imagine tracking the queue size over time as a graph. Most of the time, it hovers around its average value. Occasionally, it spikes up due to a burst of arrivals. The tail probability P(Queue $\gt$ N) tells us how often these spikes exceed level N.

For both M/M/1 and M/D/1, these probabilities decay exponentially with N, but the decay rates differ. The M/D/1 queue “decays” faster, meaning large queues are even rarer than in M/M/1.

Queueing theory is a rabbit hole of its own, and diving deep into M/D/1 would take us too far afield. I’ll likely cover that in a separate post down the line. However, we can look at M/D/1 Tail probability behavior using Large Deviation (LD) approximation, which can be given as:

\(\hspace{5cm} P\{Q \gt N\} \approx C_{q}e^{-\theta N}\) with $\theta$ solving $\rho(e^{\theta}-1) = \theta$ and $C_{q}=\frac{1-\rho}{\rho+e^{-\theta}}$.

The way to solve theta $\theta$ is by using iterative algo’s like Newton-Raphson method. If we want the Queue to be no larger than some target $P_{max}$ (e.g. $10^{-6}$), We can figure it out by using inequality

\[\hspace{5cm} C_{q}e^{-\theta N} \leq P_{max}\]Which will reduce to

\[\hspace{5cm} \begin{equation} N \geq \frac{logC_{q} - logP_{max}}{\theta} \end{equation}\]For example, if we want to find what are the chances i.e. on an average at most one packet in a million arrives to a full queue, and what should be the size of the queue when the utilization rate is 90% ($\rho = 0.9$). Solving for the above equation, we get ~53 cells, which is $\approx 13.5kB$.

Conclusion

This turned out longer than planned—classic case of flow control without a rate limiter :). I will leave the final conclusions to you. If you found it helpful, great! And if you spot any errors, think of them as lost packets—feel free to resend with corrections.

References

- CS-534: Credit Based Flow Control

- The Geometry of M/D/1 Queues and Large Deviation

- Buffer requirements of credit-based flow control when a minimum draining rate is guaranteed

- Determining Priority Flow Control Headroom

- Annex N Updates

- Receiver-Oriented Adaptive Buffer Allocation in Credit-Based Flow Control for ATM Networks